Outcomes Comparison of the Veterans’ Choice Program With the Veterans Affairs Health Care System for Hepatitis C Treatment

Background: The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has been stressed by the large number of veterans requiring direct-acting antiviral (DAA) medications for hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment. The Veterans Choice Program provides VA patients more options to receive treatment. This study compared the experience of veterans who received HCV treatment through the Veterans Choice Program and those that received treatment at the VA Loma Linda Healthcare System (VALLHCS) in fiscal year (FY) 2016.

Methods: A chart review was performed on all veterans referred by VALLHCS to Choice for HCV treatment during FY 2016, and matched to veterans who received treatment at VALLHCS. Data collected included Fibrosis-4 score (Fib-4), platelet count, days elapsed between time of referral and time of appointment (wait time), rate of sustained virologic response at 12 weeks (SVR12), reason for treatment failure, and cost effectiveness.

Results: One hundred veterans were referred to Choice; 71 were seen at least once by a Choice provider, and 61 completed a treatment course. Mean Fib-4 and platelet count was 1.9 and 228,000 for the Choice population and 3.4 and 158,000 for the VALLHCS population, respectively. There was no difference in SVR12 rate. Mean wait time was 42 days for Choice vs 29 days for VALLHCS (P < .001). Choice health care providers incurred a mean $8,561.40 in additional costs per veteran seen.

Conclusions: While treatment success rates were similar between Choice and VALLHCS, the degree of liver fibrosis was more advanced in the VALLHCS population. The wait time for care was longer with Choice compared with a direct referral within the VA. While Choice offers a potential solution to providing care for veterans, the current program has unique problems that must be considered.

For an internal referral for HCV treatment at VALLHCS, the hepatology provider submits a consult request to the HCV treatment provider, who works in the same office, making direct communication simple. The main administrative limiting factor to minimizing wait times is the number of HCPs, which is dependent on hiring allowances.

When a veteran is referred to Choice, the VA provider places a consult for non-VA care, which the VA Office of Community Care processes by compiling relevant documents and sending the package to Triwest Healthcare Alliance, a private insurance processor contracted with the VA. Triwest selects the Choice provider, often without any input from the VA, and arranges the veteran’s initial appointment.22 Geographic distance to the veteran’s address is the main selection criteria for Triwest. Documents sent between the Choice and VA HCPs go through the Office of Community Care and Triwest. This significantly increases the potential for delays and failed communication. Triwest had a comprehensive list of providers deemed to be qualified to treat HCV within the geographic catchment of VALLHCS. This list was reviewed, and all veterans referred to Choice had HCPs near their home address; therefore, availability of Choice HCPs was not an issue.

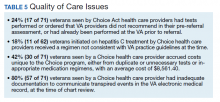

The VA can provide guidance on management of the veteran in the form of bundle packages containing a list of services for which the Choice provider is authorized to provide, and ones the Choice provider is not authorized to provide. Some Choice HCPs ordered tests that were not authorized for HCV treatment such as esophagogastroduodenoscopy, colonoscopy, and liver biopsy. In all, 17 of 71 (24%) veterans seen by Choice HCPs had tests performed or ordered that VA HCPs would not have obtained for the purpose of HCV treatment (Table 5).

In order to prevent veterans from receiving unnecessary tests, a VALLHCS hepatologist asked to be notified by VA administrators overseeing Choice referrals whenever a secondary authorization request (SAR) was submitted by a Choice HCP. This strategy is not standard VA practice, therefore at many VA sites these requested tests would have been performed by the Choice HCP, which is why SARs were factored into cost analysis.

SVR12 test results that were drawn too early and had to be repeated at VALLHCS were a cost unique to the Choice program. Duplicate tests, particularly imaging studies and blood work, were extraneous costs. The largest extraneous costs were treatment regimens prescribed by Choice HCPs that did not follow standard of care and required VA provider intervention. Thirty of the 71 (42%) veterans seen by a Choice provider accrued a mean $8,561.40 in extra costs. As a result, the Choice program cost VHA $250,000 more to provide care for 30 veterans (enough to pay for a physician’s annual salary).

Some inappropriate treatment regimens were the result of Choice HCP error, such as 1 case in which a veteran was inadvertently switched from ledipasvir/sofosbuvir to ombitasvir/ paritaprevir/ritonavir/dasabuvir after week 4. The veteran had to start therapy over but still achieved SVR12. Other cases saw veterans receive regimens for which they had clear contraindications, such as creatinine clearance < 30 mL/min/1.73m2 for sofosbuvir or a positive resistance panel for specific medications. Eleven of 62 (18%) veterans who were started on HCV treatment by a Choice HCP received a regimen not consistent with VA guidelines—an alarming result.

Follow up for veterans referred to Choice was extremely labor intensive, and assessment of personnel requirements in a Choice-based VA system must take this into consideration. The Choice HCP has no obligation to communicate with the VA HCP. At the time of chart review, 57 of 71 (80%) Choice veterans had inadequate documentation to make a confident assessment of the treatment outcome. Multiple calls to the offices of the Choice HCP were needed to acquire records, and veterans had to be tracked down for additional tests. Veterans often would complete treatment and stop following up with the Choice provider before SVR12 confirmation. The VA hepatology provider reviewing Choice referrals served as clinician, case manager, and clerk in order to get veterans to an appropriate end point in their hepatitis C treatment, with mostly unmeasured hours of work.