Outcomes Comparison of the Veterans’ Choice Program With the Veterans Affairs Health Care System for Hepatitis C Treatment

Background: The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has been stressed by the large number of veterans requiring direct-acting antiviral (DAA) medications for hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment. The Veterans Choice Program provides VA patients more options to receive treatment. This study compared the experience of veterans who received HCV treatment through the Veterans Choice Program and those that received treatment at the VA Loma Linda Healthcare System (VALLHCS) in fiscal year (FY) 2016.

Methods: A chart review was performed on all veterans referred by VALLHCS to Choice for HCV treatment during FY 2016, and matched to veterans who received treatment at VALLHCS. Data collected included Fibrosis-4 score (Fib-4), platelet count, days elapsed between time of referral and time of appointment (wait time), rate of sustained virologic response at 12 weeks (SVR12), reason for treatment failure, and cost effectiveness.

Results: One hundred veterans were referred to Choice; 71 were seen at least once by a Choice provider, and 61 completed a treatment course. Mean Fib-4 and platelet count was 1.9 and 228,000 for the Choice population and 3.4 and 158,000 for the VALLHCS population, respectively. There was no difference in SVR12 rate. Mean wait time was 42 days for Choice vs 29 days for VALLHCS (P < .001). Choice health care providers incurred a mean $8,561.40 in additional costs per veteran seen.

Conclusions: While treatment success rates were similar between Choice and VALLHCS, the degree of liver fibrosis was more advanced in the VALLHCS population. The wait time for care was longer with Choice compared with a direct referral within the VA. While Choice offers a potential solution to providing care for veterans, the current program has unique problems that must be considered.

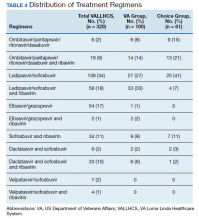

The mean wait time from referral to appointment was 28.6 days for the VA group and 42.3 days for the Choice group (P < .001), indicating that a Choice referral took longer to complete than a referral within the VA for HCV treatment. Thirty of the 71 (42%) veterans seen by a Choice provider accrued extraneous cost, with a mean additional cost of $8,561.40 per veteran. In the Choice group, 61 veterans completed a treatment regimen with the Choice HCP. Fifty-five veterans completed treatment and had available SVR12 data (6 were lost to follow up without SVR12 testing) and 50 (91%) had confirmed SVR12. The charts of the 5 treatment failures were reviewed to discern the cause for failure. Two cases involved early termination of therapy, 3 involved relapse and 2 failed to comply with medication instructions. There was 1 case of the Choice HCP not addressing simultaneous use of ledipasvir and a proton pump inhibitor, potentially causing an interaction, and 1 case where both the VA and Choice providers failed to recognize indicators of cirrhosis, which impacted the regimen used.

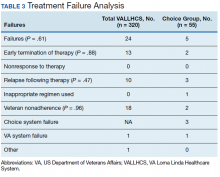

In the VALLHCS group, records of 320 veterans who completed treatment and had SVR12 testing were reviewed. While the Choice memorandum was active, veterans selected to be treated at VALLHCS had advanced liver fibrosis or cirrhosis, medical and mental health comorbidities that increased the risk of treatment complications or were considered to have difficulty adhering to the medication regimen. For this group, 296 (93%) had confirmed SVR12. Eighteen of the 24 (75%) treatment failures were complicated by nonadherence, including all 13 cases of early termination. One patient died from complications of decompensated cirrhosis before completing treatment, and 1 did not receive HCV medications during a hospital admission due to poor coordination of care between the VA inpatient and outpatient pharmacy services, leading to multiple missed doses.

The difference in SVR12 rates (ie, treatment failure rates), between the VA and Choice groups was not statistically significant (P = .61). None of the specific reasons for treatment failure had a statistically significant difference between groups. A treatment failure analysis is shown in Table 3, and Table 4 indicates the breakdown of treatment regimens.

Discussion

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the largest integrated health care system in the US, consisting of 152 medical centers and > 1,700 sites of care. The VA has the potential to meet the health care needs of 21.6 million veterans. About 9 million veterans are enrolled in the VA system and 5.9 million received health care through VHA.17 However, every medical service cannot realistically be made available at every facility, and some veterans have difficulty gaining access to VHA care; distance and wait times have been well-publicized issues that need further exploration.18,19 The Choice program is an attempt to meet gaps in VA coverage using non-VA HCPs.

HCV infection is a specific diagnosis with national treatment guidelines and wellstudied treatments; it can be cured, with an evidence- based definition of cure. The VACO policy memorandum to refer less sick veterans to Choice while treating sicker veterans at the VA provided the opportunity to directly compare the quality of the 2 programs. The SVR12 rates of VALLHCS and Choice providers were comparable to the national average at the time, and while the difference in SVR12 rate was not significant, VALLHCS treated a significantly higher number of patients with cirrhosis because of the referral criteria.20

The significant difference in medical comorbidities between the VA and Choice groups was not surprising, partly because of the referral criteria. Cirrhosis can impact the treatment regimen, especially in regard to use of ribavirin. Since the presence of mental health comorbidities did not affect selection into the Choice group, it makes sense that there was no significant difference in prevalence between the groups.

VACO allowed veterans with HCV treatment plans that VA HCPs felt were too complicated for the Choice program to be treated by VHA HCPs.9 VALLHCS exercised this right for veterans at risk for nonadherence, because in HCV treatment, nonadherence leads to treatment failure and development of drug resistant virus strains. Therefore, veterans who would have difficulty traveling to VALLHCS to pick up medications, those who lacked means of communication (such as those who were homeless), and those who had active substance abuse were treated at the VA, where closer monitoring and immediate access to a wide range of services was possible. Studies have confirmed the impact of these types of issues on HCV treatment adherence and success. 21 This explains the higher prevalence of social issues in the VA group.