The VA My Life My Story Project: Keeping Medical Students and Veterans Socially Connected While Physically Distanced

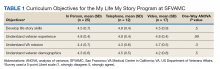

Introduction: Narrative competence comprises the skills of acknowledging, interpreting, and acting on the stories of others. Developing narrative competence is integral to providing patient-centered care. In January 2020, we designed a narrative medicine curriculum in which medical students at the San Francisco Veteran Affairs (VA) Medical Center in California participated as interviewers in My Life My Story (MLMS) program. The curricular objectives for medical students were to build life story skills, appreciate the impact of storytelling on a veteran’s health care experience, and understand the VA mission.

Observations: Students attended a training session to build narrative medicine skills, interviewed a veteran, entered their life story into the health record, and attended a second session to debrief. Students completed a survey after the MLMS program. From March to July 2020, COVID-19-related restrictions prompted transition of the program to a virtual format. Sixty-two veteran stories were collected, and 54 (87%) veterans requested that their stories be entered into the health record. Students reported that the program helped them develop life story collection skills and understand how sharing a life story can impact a veteran’s experience of receiving health care. There was no statistically significant difference in survey responses whether interviews were in person, by telephone, or over video.

Conclusions: A curriculum incorporating MLMS effectively taught narrative medicine skills to medical students. The program achieved its objectives despite curricular redesign for the virtual setting. This report details an adaptation of a life story-focused narrative medicine curriculum to a virtual environment and can inform similar programs at other VA medical centers.

COVID-19-Related Adaptation

In March 2020, shortly after the second student cohort began, medical students were removed from the clinical setting in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The 8-week clerkship was converted to a 3-week remote learning rotation. The MLMS experience was preserved by converting small group sessions to videoconferences and expanding the pool of eligible patients to include veterans who students had met on prior rotations, current inpatients, and outpatients from VA primary care clinics. Students contacted veterans after an instructor had introduced MLMS to the veteran and confirmed that the veteran was interested in participating.

Students in the second and third cohorts completed a telephone-based iteration of MLMS in which interviews and life story reviews were conducted over the telephone and printed copies mailed to the veteran. For the fourth, fifth, and sixth cohorts, MLMS was transitioned to a video-based program with inpatients. Instructors collaborated with a volunteer group supplying tablet devices to inpatients to make video calls to their families during the pandemic.14 Clerkship students coordinated with that volunteer group to interview veterans and review their stories through the tablet devices.

From July to December 2020 medical students returned to 4-week on-site clinical rotations at the SFVAMC. The program returned to the original format for cohorts 7 to 10, with students attending in-person small group sessions and conducting in-person interviews with inpatients.

Curriculum Evaluation

Students completed surveys in the week after the curriculum concluded. Survey completion was voluntary, anonymous, and had no bearing on their evaluation or grade (pass/fail only). Likert scale questions (1, strongly disagree; 5, strongly agree) were used to assess the program (eAppendix 1). One-way analysis of variance testing was used to compare means stratified by method of interview (in person, telephone, or video). Surveys also included free-response questions asking students to highlight aspects of the program they valued or would change; responses were summarized by theme. This program evaluation was deemed exempt from review by the UCSF Human Research Protection Program Institutional Review Board.

Sixty-two veteran stories were collected by 54 participating students (one student was unable to complete an interview, while several students completed multiple interviews). Fifty-four (87%) veterans requested their stories be entered into the medical record.

All 54 students completed the survey. Students reported that the MLMS curriculum helped them develop new skills for eliciting and recording a life story (mean [SD] 4.5 [0.7]). Most students strongly agreed that MLMS helped them understand how sharing a life story can impact a veteran’s experience of receiving health care, with a mean (SD) score of 4.8 (0.4). After completing MLMS, students also reported a better understanding of the mission of the VA and veteran demographics with a mean (SD) score of 4.4 (0.7) and 4.3 (0.7), respectively. Stratification of survey responses by method of interview (in person, telephone, or video) revealed no statistically significant differences in evaluations (Table 1).

Fifty-two (96%) students provided responses to free-response survey questions. Students reported that they valued shifting the focus of an interview from medical history to rapport-building and patient engagement, having protected time to focus on the humanistic aspect of doctoring, and redefining healing as a process that occurs in the greater context of a patient’s life. One student reported, “We talk so much about seeing the person instead of the disease, but this is the first time that I really felt like I had the opportunity to wholeheartedly commit myself to that. It was an incredible opportunity and something I wish all medical trainees would have the chance to do.” Another student, after participating in the video version of the project, reported, “I found so much comfort in the time that I just sat and listened to another person’s story firsthand. Not only did this opportunity remind me of why I wanted to work in medicine, but also why I wanted to work with and for other people.” Thirty-three (61%) students provided constructive feedback in response to a free-response question soliciting suggestions for improvement, which guided iterative programmatic changes. For example, 3 students who completed the telephone iteration of MLMS felt that patient engagement suffered due to the lack of nonverbal cues and body language that can enhance the bond between storyteller and interviewer. This prompted a switch to video interviews beginning with the fourth cohort.