The VA My Life My Story Project: Keeping Medical Students and Veterans Socially Connected While Physically Distanced

Introduction: Narrative competence comprises the skills of acknowledging, interpreting, and acting on the stories of others. Developing narrative competence is integral to providing patient-centered care. In January 2020, we designed a narrative medicine curriculum in which medical students at the San Francisco Veteran Affairs (VA) Medical Center in California participated as interviewers in My Life My Story (MLMS) program. The curricular objectives for medical students were to build life story skills, appreciate the impact of storytelling on a veteran’s health care experience, and understand the VA mission.

Observations: Students attended a training session to build narrative medicine skills, interviewed a veteran, entered their life story into the health record, and attended a second session to debrief. Students completed a survey after the MLMS program. From March to July 2020, COVID-19-related restrictions prompted transition of the program to a virtual format. Sixty-two veteran stories were collected, and 54 (87%) veterans requested that their stories be entered into the health record. Students reported that the program helped them develop life story collection skills and understand how sharing a life story can impact a veteran’s experience of receiving health care. There was no statistically significant difference in survey responses whether interviews were in person, by telephone, or over video.

Conclusions: A curriculum incorporating MLMS effectively taught narrative medicine skills to medical students. The program achieved its objectives despite curricular redesign for the virtual setting. This report details an adaptation of a life story-focused narrative medicine curriculum to a virtual environment and can inform similar programs at other VA medical centers.

The second small group session provided space for students to reflect on their experience. During this session, students frequently referenced the unique connections they developed with veterans. Several students described feeling refreshed by these connections and that MLMS helped them recall their original commitment to become physicians. Students also discovered that the events veterans included in their stories often echoed current societal issues. For example, as social unrest and protests related to racial injustice occurred in the summer of 2020, veterans’ life stories more frequently incorporated examples of prejudice or inequities in the justice system. As the use of force by police moved to the forefront of political discourse, life stories more often included veterans’ experiences working as military and nonmilitary law enforcement. In identifying these common themes, students reported a greater appreciation of the impact of society on patients’ overall health and well-being.

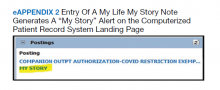

Stories were recorded as CPRS notes titled “My Story,” and completion of a note generated a “My Story” alert on the CPRS landing page at the SFVAMC (eAppendix 2). Physicians and nurses who have discovered the notes reported that patient care has been enhanced by the contextualization provided by a life story. HCPs now frequently contact MLMS instructors inquiring whether students are available to collect life stories for their patients. One physician wrote, “I learned so much from what you documented—much more than I could appreciate in my clinic visits with him. His voice comes shining through. Thank you for highlighting the humanism of medicine in the medical record.” Another physician noted, “The story captured his voice so well. I reread it over the weekend after I got the news that he died, and it helped me celebrate his life. Please tell your students how much their work means to patients, families, and the providers who care for them.”

Discussion

Previous research has demonstrated that a narrative medicine curriculum can help medicine clerkship students develop narrative competence through patient storytelling with a focus on a patient’s illness narrative.15 The VA MLMS program extends the patient narrative beyond health care–related experiences and encompasses their broader life story. This article adds to the MLMS and narrative medicine literature by demonstrating that the efficacy of teaching patient-centered care to medical trainees through direct interviews can be maintained in remote formats.9 The article also provides guidance for MLMS programs that wish to conduct remote veteran interviews.

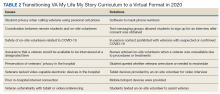

The widespread adoption of telemedicine will require trainees to develop communication skills to establish therapeutic relationships with patients both face-to-face and through videoconferencing. In order to promote this important skill across varying levels of physical distancing, narrative medicine programs should be adaptable to a virtual learning environment. As we redesigned MLMS for the remote setting, we learned several key lessons that can guide similar curricular and programmatic innovations at other institutions. For example, videoconferencing created stronger connections between the students and veterans than telephone calls. However, tablet-based video interviews also introduced many technological challenges and required on-site personnel (nurses and volunteers) to connect students, veterans, and technology. Solutions for technology and communication challenges related to the basic personnel and infrastructure needed to start and maintain a remote MLMS program are outlined in Table 2.

We are now using this experience to guide the expansion of life story curricula to other affiliated clerkship sites and other medical student rotations. We also are expanding the interviewer pool beyond medical students to VA staff and volunteers, some of whom may be restricted from direct patient contact in the future but who could participate through the remote protocols that we developed.

Limitations

Limitations of this study include the participation of trainees from a single institution and a lack of assessment of the impact of MLMS on veterans. Future research could assess whether life story skills and practices are maintained after the medicine clerkship. In addition, future studies could examine veterans’ perspectives through interviews with qualitative analysis to learn how MLMS affected their experience of receiving health care.

Conclusions

This is the first report of a remote-capable life story curriculum for medical students. Shifting to a virtual MLMS curriculum requires protocols and people to link interviewers, veterans, and technology. Training for in-person interactions while being prepared for remote interviewing is essential to ensure that the MLMS experience remains available to interviewers and veterans who otherwise may never have the chance to connect. The restrictions and isolation of the COVID-19 pandemic will fade, but using MLMS to virtually connect patients, providers, and students will remain an important capability and opportunity as health care shifts to more virtual interaction.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Emma Levine, MD, for her assistance coordinating video interviews; Thor Ringler, MS, MFA, for his assistance with manuscript review; and the veterans of the San Francisco VA Health Care System for sharing their stories.