Minimally invasive surgery in ovarian cancer

Laparoscopy has dramatically altered management of many gynecologic malignancies, but its utility in ovarian cancer has been limited—until now.

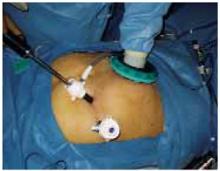

The nondominant hand and surgical instruments can be inserted and removed through the special port without affecting pneumoperitoneum.

Surgical Staging

Maria’ case

resection and analysis of ovary

Maria underwent laparoscopy via the open technique. The surgeon found a cystic right ovarian mass, a fibroid uterus, and small diaphragmatic nodules, which were biopsied and found to be benign.

Pelvic washings were obtained, and after the right infundibular pelvic ligament and right utero-ovarian ligament were clamped and cut, the intact ovary was placed in a laparoscopic bag. The bag was pulled through the 12-mm suprapubic trocar, the cyst wall was perforated, and the cyst was drained within the laparoscopic bag, producing brown fluid. The bag was removed from the peritoneal cavity through this port, and the cyst was sent to pathology.

There was no contamination to the peritoneal cavity or abdominal wall, and the bag remained intact. Surgical gloves were then changed, and instruments used to drain the cyst were removed from the operating field.

When frozen-section analysis revealed a borderline serous ovarian tumor, Maria underwent BSO, infracolic omentectomy, laparoscopic pelvic and paraaortic lymphadenectomy, and laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy. There were no intraoperative complications, the total time in the operating room was 330 minutes, and there was blood loss of approximately 150 mL.

When an ovarian malignancy is discovered, immediate staging is indicated, and should include:

- peritoneal biopsies,

- pelvic and para-aortic lymph node sampling,

- infracolic omentectomy, and

- bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) and hysterectomy.1

With presumed stage I disease, there is a 20% to 30% likelihood of upstaging after comprehensive surgical staging, with disease often discovered in the lymph nodes.19,20

Since changes in staging affect prognosis and treatment, complete staging should include the retroperitoneal nodes.

When the patient wants to preserve fertility

In selected younger women who have not yet completed childbearing, conservative treatment with retention of the uterus and contralateral ovary is an option—though we lack outcomes data on patients treated this way.

This option should be restricted to women with proven stage I disease after comprehensive staging.1

Can staging be done laparoscopically?

Complete staging—consisting of a detailed peritoneal assessment (with BSO and vaginal hysterectomy), omentectomy, and pelvic and para-aortic node dissection—can safely be done laparoscopically.19-21 Studies show low morbidity, with accurate findings and adequate node counts.21,22

A comparison of laparoscopic and conventional (laparotomy) staging in women with apparent stage I adnexal cancers found no differences in omental specimen size or the number of lymph nodes removed, and none of the patients required conversion to laparotomy.22

When definitive staging is delayed

Several studies have found poorer outcomes with delayed staging. However, the tumor ruptured in some of these studies, with considerable delay from the initial laparoscopy until definitive staging and treatment.

To increase the likelihood of an accurate stage, gather as much information as possible on the extent of disease: Describe the intraoperative findings and inspect the abdomen and pelvis thoroughly at initial surgery if a skilled oncologic surgeon is not immediately available. Then make every effort to schedule a complete staging procedure as soon as possible, as some consider this an “oncologic emergency.”9

Whether and when to stage LMP tumors

Preoperative prediction and intraoperative diagnosis of low malignant potential (LMP) tumors is challenging. If such a tumor is confirmed by frozen section, the usual treatment is unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. When the patient is postmenopausal or has completed childbearing, BSO, hysterectomy, and staging should be considered.1

Surgical staging should be performed at the initial surgery, if at all possible. However, if final pathology confirms an LMP tumor and disease appears to be confined to the adnexa, repeat surgery for staging is controversial because of the limited data on its benefit, particularly in regard to mucinous borderline tumors.

Restaging may be more useful in selected cases of serous LMP tumors with histologic micropapillary features, since these tumors may be associated with a higher incidence of invasive implants (eg, in the omentum or peritoneum) that may require chemotherapy.

If a malignant cyst ruptures, does it affect staging?

The effect of intraoperative tumor spillage in stage I disease is debatable, although ascites and preoperative rupture are associated with a poorer prognosis.23

Even though a number of investigators (TABLE) have found intraoperative spillage to have no adverse impact on survival, make every effort to maintain capsular integrity to minimize any possibility of peritoneal tumor dissemination.

In some cases, intraoperative cyst rupture warrants upstaging from International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage IA to 1C, necessitating adjuvant chemotherapy when it otherwise would not have been required.1