Cost-conscious choices for minimally invasive gynecologic surgery

Attention to the costs of the surgical devices, instruments, and related products you use can help ensure greater value for the care you provide—and may just help you maximize reimbursement, too

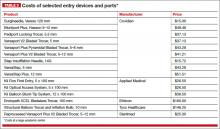

Entry style and ports

The peritoneal cavity can be entered using either a closed (Veress needle) or open (Hasson) technique.5 Closed entry may allow for quicker access to the peritoneal cavity. A recent Cochrane review of 28 randomized, controlled trials, including 4,860 patients undergoing laparoscopy, compared outcomes between laparoscopic entry techniques.6 It found no difference in major vascular or visceral injury between closed and open techniques at the umbilicus. However, open entry was associated with greater successful entry into the peritoneal cavity, as well as less extraperitoneal insufflation and a lower omental injury rate, compared with closed entry.6

Left-upper-quadrant entry is another option when adhesions are anticipated or abnormal anatomy is encountered at the umbilicus.

In general, complications related to laparoscopic entry are quite rare in gynecologic surgery, ranging from 0.18% to 0.5%.7,8 A minimally invasive surgeon may prefer one entry technique over the other, but should be able to perform both methods competently and recognize when a particular technique is warranted.

Choosing a port

Laparoscopic ports usually range from 5 mm to 12 mm and can be fixed or variable in size. The primary port, usually placed through the umbilicus, can be a standard, blunt, 10-mm (Hasson) port, or it can be specialized to ease entry of the port or stabilize the port once it is introduced through the skin incision.

Optical trocars have a transparent tip that allows the surgeon to visualize the abdominal-wall entry layer by layer using a 0° laparoscope, usually after pneumoperitoneum is created with a Veress needle. Other specialized ports include those that have balloons or foam collars, or both, to secure the port without traditional stay sutures on the fascia and minimize leakage of pneumoperitoneum.

Accessory ports

When choosing an accessory port type and size, it is important to anticipate what instruments and devices, such as an Endo Catch bag, suture, needle, or morcellator, will need to pass through it. Also know whether 5-mm and 10-mm laparoscopes are available, and anticipate whether a second port with insufflation capabilities will be required.

Related article: Update on Minimally Invasive Surgery Amy Garcia, MD (April 2011)

Pediport trocars are user-friendly 5-mm bladed ports that deploy a mushroom-shaped stabilizer to prevent dislodgement. A Versaport bladed trocar has a spring-loaded entry shield, which slides over to protect the blade once the peritoneal cavity is entered.

VersaStep bladeless trocars are introduced after a Step insufflation needle has been inserted. These trocars create a smaller fascial defect than conventional bladed trocars for an equivalent cannula size (TABLE 3).

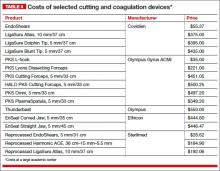

Cutting and coagulating

Both monopolar and bipolar electrosurgical techniques are commonly employed in gynecologic laparoscopy. A wide variety of disposable and reusable instruments are available for monopolar energy, such as scissors, a hook, and a spatula.

Bipolar devices also can be disposable or reusable. Although bipolar electrosurgery minimizes injury to surrounding tissues by containing the current within the jaws of the forceps, it cannot cut or seal large vessels. As a result, several advanced bipolar devices with sealing and transecting capabilities have emerged (LigaSure, ENSEAL). Ultrasonic devices also can coagulate and cut at lower temperatures by converting electrical energy to mechanical energy (TABLE 4).

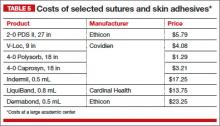

Sutures

Aspects of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery that require the use of suture include, but are not limited to, closure of the vaginal cuff, oophoropexy, and reapproximation of the ovarian cortex after cystectomy. Syntheticand delayed absorbable sutures, such as PDS II, are used frequently.

Recently, a new class of suture emerged and continues to gain popularity: barbed suture. This type of suture anchors to the tissue without the need for intra- or extracorporeal knots (TABLE 5).

Related article: Ins and outs of straight-stick laparoscopic myomectomy James Robinson, MD, MS, and Gaby Moawad, MD (September 2012)

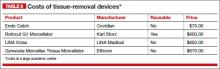

Tissue removal

Adnexae and pathologic tissue, such as dermoid cysts, can be removed intact from the peritoneal cavity using an Endo Catch Single-Use Specimen Pouch, a polyurethane sac. Careful use, with placement of the ovary with the cyst into the pouch prior to cystectomy, can prevent spillage beyond the bag.

Large uteri that cannot be extracted through a colpotomy can be morcellated into smaller pieces to ease removal through a small laparoscopic incision or the colpotomy. Both reusable and disposable morcellator hand pieces are available (TABLE 6).

Skin closure

Final subcuticular closure can be accomplished using sutures or skin adhesive. Sutures may be synthetic, absorbable monofilament (eg, Caprosyn), or synthetic, absorbable, braided multifilament (eg, PolySorb).

Related article: 10 practical, evidence-based recommendations for improving maternal outcomes of cesarean delivery Baha M. Sibai, MD (March 2012)

Skin adhesives close incisions quickly, avoid inflammation related to foreign bodies, and ease patient concerns that sometimes arise when absorbable suture persists postoperatively (TABLE 5).