How to avoid major vessel injury during gynecologic laparoscopy

Attention to anatomy, entry techniques, and operative devices can help avert serious injury. Also vital is a plan to manage potential complications.

IN THIS ARTICLE

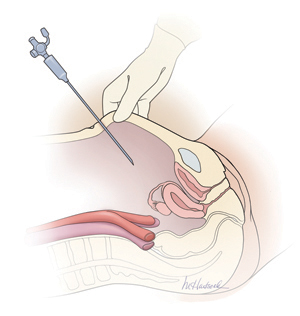

Most laparoscopic surgeons stand on the left-hand side of the patient and face her feet. Trocar deviation for a right-handed person tends to vector to the right, especially when a twisting motion is utilized. Correct alignment of the primary trocar is straight down the middle of the lower abdomen on a virtual or real line drawn from the center of the navel to the center of the symphysis.

An entry angle of 45° to 60° will carry the needle or trocar toward the bladder or uterus and away from the aorta and left common iliac vein. In contrast, a 90° thrust will aim the device dangerously toward the great vessels. A slightly upward and right-sided deviation from the subumbilical entry will place the needle and trocar in the direction of the inferior vena cava and right common iliac vessels. A 90° entry with deviation to the left will position the entry device at the inferior mesenteric vessels and the left common iliac vessels.

Primary abdominal entry

An entry angle of 45° to 60°, regardless of whether a needle or trocar is used, will carry the device toward the bladder or uterus and away from the aorta and left common iliac vein.In a review of access complications associated with laparoscopy, including major vascular injuries, Philips and Amaral listed variables responsible for large-vessel injury; they also documented the incidence of such injuries associated with laparoscopic cholecystectomy.8 They recommended that the patient be placed in the Trendelenburg position and that the needle or trocar be inserted at a 45° angle that stays within the midline; they also concluded that the trocar should be placed when pneumoperitoneal pressures exceed 20 mm Hg. They advised against direct insertion in patients with a history of pelvic surgery as well as in thin patients.

Place secondary trocars under direct visualization

Secondary trocars should always be placed under direct, visually controlled entry and, at least hypothetically, should never injure any great vessel. Nevertheless, secondary trocars do sometimes cause injury, most often as a result of extreme lateral entry near the inguinal ligament. The vessels at risk are the external iliac artery and vein.

Injuries are also invariably associated with adhesiolysis and anatomic problems. Precise knowledge of pelvic anatomy is not only a requisite for pelvic surgery in general but also for laparoscopic surgery, in which the operative view is less clear than it is in open procedures.

Know the risks associated with operative tools

Suturing and knot tying are not easy maneuvers during laparoscopic procedures and add significant operative time. Although they are performed more easily when robotics is utilized, few gynecologists are skilled practitioners. As a result, accessory instruments have been developed to prevent and control bleeding during laparoscopic operations. These devices include monopolar and bipolar instruments, lasers, ultrasonic tools, and stapling devices.

Avoid monopolar electrosurgery

This modality should be avoided whenever possible because the risk of injury is significantly higher than with bipolar electrosurgery. The key disadvantages of monopolar energy are high-frequency leaks; low-frequency currents; direct, indirect, and capacitative coupling; and return-electrode failures. None of these problems are common with bipolar techniques.

However, all electrosurgical devices carry a risk of thermal injury through direct tissue contact and conduction of heat to neighboring tissues and structures.

A full discussion of the physics and tissue actions of electrosurgical devices may be found elsewhere.9

CO2 is the safest laser

A variety of lasers have been used in laparoscopic surgery. The neodymium–YAG, KTP-532, and CO2 lasers have been used most frequently for gynecologic operations.

Because of its wavelength, the CO2 laser is the safest device for intra-abdominal use. Advantages include precision and control. In addition, the CO2 laser is absorbed by water very effectively. As a result, hydrodissection techniques can facilitate effective backstopping of the laser beam in strategic locations, thereby preventing injury to surrounding structures.

Laser energy is not conducted through tissue in the same way that electrosurgical energy is conducted. Therefore, the laser is ideal for vaporizing endometrial implants and cutting adhesions.

Beware of heat generated by the ultrasonic shears

This device, known more commonly as the Harmonic Scalpel (Ethicon), employs high-frequency sound waves to shear and coagulate tissue and prevent bleeding. It does not require conduction through tissues but does require contact with tissues. Because friction produces heat, these devices can become hot enough to inflict unintended burns on tissues that are inadvertently touched by the hot tip or by heat transmitted from the operative site by thermal conduction.

Stapler may inadvertently involve adjacent structures

This laparoscopic device has the advantage of not requiring or emitting energy other than the mechanical force of the operator’s hand. Disadvantages associated with the stapler center on the inadvertent inclusion of other structures within the jaws of the instrument. In addition, the staplers themselves tend to be large and somewhat unwieldy in close quarters, adding to the risk of stapling nearby viscera.