Laparoscopic challenges: The large uterus

Total laparoscopic hysterectomy is possible when the uterus is larger than 14 weeks’ gestational size—if you incorporate several novel techniques and use the right instruments

IN THIS ARTICLE

Control the blood supply

Our laparoscopic approach is very similar to our technique for abdominal hysterectomy, beginning with the blood supply. The main blood supply to the uterus enters at only four points. If this blood supply is adequately controlled, morcellation of the large uterus can proceed without excessive blood loss.

Visualization of the blood supply is normally restricted because of tense, taut round ligaments that limit mobility of the large uterus. A simple step to improve mobility is to transect each round ligament in its middle position before addressing the uterine blood supply.

If the ovaries are being conserved, transect the utero-ovarian ligament and tube as close to the ovary as possible with your instrument and technique of choice (electrical or mechanical energy, etc); they all work. Stay close to the ovary to avert bleeding that might otherwise occur when the ascending uterine vascular coils are cut tangentially.

If the ovaries are being removed, transect the infundibulopelvic ligament close to the ovary, being careful not to include ovarian tissue in the pedicle. Use your method of choice, but relieve tension on the pedicle as it is being transected to minimize the risk of pedicle bleeding.

Now, 20% to 40% of the uterine blood supply is controlled, with minimal blood loss.

The key to controlling the remaining blood supply is transecting the ascending vascular bundle as low as possible on either side. The 45° endoscope provides optimal visualization for this part of the procedure. Many times the field of view attained using the 45° endoscope is all that is necessary to facilitate occlusion and transection of these vessels at the level of the internal cervical os.

We commonly use ultrasonic energy to coagulate and cut the ascending vascular bundle. Ultrasonic energy provides excellent hemostasis for this part of the procedure. Again, use the technique of your choice.

Use a laparoscopic “leash”

At times, large broad-ligament fibroids obscure the field of view and access to the ascending vascular bundle. Standard laparoscopic graspers cannot maintain a firm hold on the tissue to improve visibility or access. The solution? A laparoscopic “leash,” first described in 1999 by Tsin and colleagues.13

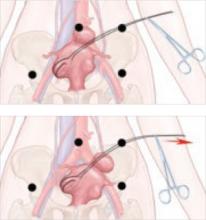

Giesler extended that concept with a “puppet string” variation to maximize exposure in difficult cases. To apply the “puppet string” technique, using No. 1 Prolene suture, place a large figure-of-eight suture through the tissue to be retracted (FIGURE 4). Bring the suture out of the abdomen adjacent to the trocar sleeve in a location that provides optimal traction. (First, bring the suture through the trocar sleeve. Then remove the trocar sleeve and reinsert it adjacent to the retraction suture.) This secure attachment allows better visualization and greater access to the blood supply at a lower level. It also is possible to manipulate this suture inside the abdomen using traditional graspers to provide reliable repositioning of the uterus. This degree of tissue control improves field of vision and allows the procedure to advance smoothly.

FIGURE 4 A “puppet string” improves access

This secure attachment allows better visualization and greater access to the blood supply at a lower level. Manipulation of this suture inside the abdomen using traditional graspers also helps reposition the uterus.

Morcellation techniques

Once the ascending blood supply has been managed on both sides, morcellation can be performed with minimal blood loss using one of two techniques:

- Amputate the body of the uterus above the level where the blood supply has been interrupted

- Morcellate the uterine body to a point just above the level where the blood supply has been interrupted.

Use basic principles, regardless of the technique chosen

- Hold the morcellator in one hand and a toothed grasper in the other hand to pull tissue into the morcellator. Do not push the morcellator into tissue or you may injure nonvisualized structures on the other side.

- Morcellate tissue in half-moon portions, skimming along the top of the fundus, instead of coring the uterus like an apple; it creates longer strips of tissue and is faster. This technique also allows continuous observation of the active blade, which helps avoid inadvertent injury to tissues behind the blade.

- Attempt morcellation in the anterior abdominal space to avoid injury to blood vessels, ureters, and bowel in the posterior abdominal space. The assistant feeds uterine tissue to the surgeon in the anterior space.

It is essential to control the blood supply to the tissue to be morcellated before morcellation to avoid massive hemorrhage.

Amputating the upper uterine body

Amputation of the large body of the uterus from the lower uterine segment assures complete control of the blood supply and avoids further blood loss during morcellation, but it also poses difficulties. The free uterine mass is held in position by the assistant using only one grasper. If this grasper slips, the mass can be inadvertently released while the morcellator blade is active. If the assistant is also holding the camera, there are no options for stabilizing the free uterine mass. If a mechanical scope holder or second assistant is available to hold the camera, a second trocar port can be placed on the side of the assistant to provide access for a second grasper to stabilize the uterine body during morcellation. The need for a stable uterine mass is important to minimize the risk of injury.