Reducing the medicolegal risk of vacuum extraction

Focus on indications, informed consent, technique, and documentation to yield better outcomes

IN THIS ARTICLE

Indications and contraindications for vacuum extraction are similar, but not identical, to those for forceps delivery (TABLE 2).2,3 The most important determinant for either device is the experience of the operator. You must be familiar with the instrument and technique before making any attempt to assist delivery. An inability to accurately assess fetal position or station, fetopelvic proportion, adequacy of labor, engagement of the fetal head, or any degree of malpresentation (including minor degrees of deflexion) is a contraindication to a trial of operative vaginal delivery.

Vacuum extraction should be reserved for fetuses at more than 34 weeks’ gestation because of the increased risk of intracranial hemorrhage associated with prematurity.

All decisions involving vacuum extraction should be made with caution. The adequacy of the pelvis, estimated fetal size, and any suggestions of fetopelvic disproportion are of particular significance.3

FIGURE

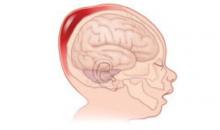

Subgaleal hemorrhage, a deadly complication

Blood can accumulate in a large potential space between the galea aponeurotica and the periosteum of the cranial bones after vacuum extraction. An infant with subgaleal hemorrhage will exhibit a boggy scalp, with swelling that crosses the suture lines and expands head circumferenceTABLE 2

Factors that predict success—or failure—of vacuum extraction

| When a woman fits overlapping categories, the decision to use vacuum extraction—or not—may be a judgment call* |

| GOOD CANDIDACY |

| Multiparous |

| Term pregnancy |

| Occiput anterior position, well-flexed |

| Wide subpubic arch |

| Compliant |

| MARGINAL CANDIDACY |

| Primiparous |

| Post-term |

| Occiput posterior position |

| Average subpubic arch |

| Gestational diabetes |

| Arrest disorders in second stage |

| POOR CANDIDACY |

| Protraction disorders in second stage |

| Narrow subpubic arch |

| Uncertain position of fetal head |

| Deflexion or asynclitism |

| Anticipated large-for-gestational-age infant |

| Poor maternal compliance |

| * When faced with a good indication in a marginal candidate, we recommend delivery in a “double setup” situation in which preparations are made for both vacuum extraction and cesarean section. If the vacuum can be properly applied, the first application of traction is crucial. We will only proceed if significant descent is achieved. If the fetal head (not the scalp) can be advanced a full station, then we proceed cautiously. If not, ready access to cesarean section allows for completion of the delivery in a timely manner. |

2. Informed consent: Elicit the patient’s desires

Thorough discussion with the patient and her family—to explain the reasoning behind the clinical decision to use the vacuum extractor and delineate the alternatives—is paramount. Moreover, the patient should be encouraged to actively participate in this discussion.

Among the alternatives to vacuum extraction are expectant observation and expedited delivery by cesarean section. Because patients increasingly are requesting elective cesarean section in the absence of obvious obstetric indications, this option should receive extra attention.

Most women still consider vaginal delivery an important milestone of female adulthood. When safety concerns arise and the situation makes vaginal delivery unwise, many women experience disappointment and postpartum depression over their “failed” attempt at vaginal delivery. These perceptions need to be addressed in discussions with the patient.

The risk–benefit equation

Vacuum extraction lessens the risk of maternal lacerations, either of the lower genital tract in the case of obstetric forceps, or of the cervix and lower uterine segment in the case of cesarean section. In addition, vacuum extraction can be performed comfortably in the absence of regional anesthesia.

Avoiding cesarean section can produce multiple benefits

Another maternal benefit of vacuum extraction is the decreased need for cesarean section. A reduction in the primary cesarean rate also lowers the need for repeat cesarean section, which can be more technically challenging than primary C-section due to the presence of dense scar tissue and intra-abdominal adhesions. Cesarean section also increases the risk of placenta accreta, increta, or percreta in subsequent pregnancies. These complications increase the likelihood of emergency hysterectomy, massive blood loss, and serious maternal morbidity and mortality.

Even in the absence of placenta accreta, both primary and repeat cesarean sections raise the risk of hemorrhage and febrile morbidity, prolong convalescence, and increase cost, compared with vaginal delivery. For these reasons, avoiding primary cesarean section can obviate the need for multiple surgical procedures and their attendant risks. The degree to which these factors favor vaginal delivery over cesarean section is subject to debate.

Maternal risks include pelvic floor trauma

Both vacuum extraction and forceps delivery increase the risk of anal sphincter injury and can impair fecal continence.4 Both methods also appear to increase trauma to the genital tract in comparison with spontaneous delivery and may predispose the woman to pelvic floor dysfunction, including urinary and anal incontinence.5-10 However, anal sphincter trauma was less frequent after vacuum extraction than after forceps delivery.1

Other maternal injuries associated with vacuum extraction include perineal lacerations and injuries to the vulva, vagina, and cervix. Vacuum extraction also has been implicated as a significant risk factor for postpartum hemorrhage11 and genital-tract infection.1