The generalist’s guide to interstitial cystitis

How to diagnose and treat all but refractory cases of this not-so-uncommon disease

Heparin is another option. It is administered at a dose of 10,000 U thrice weekly.

Hyaluronic acid. In a small study involving 20 patients, weekly intravesical hyaluronic acid improved symptoms in 65% of patients, with a 40% and 30% decrease in nocturia and pain, respectively.20

Intravesical pentosan polysulfate sodium is another option that improves symptoms and increases bladder capacity,21 although larger studies of its efficacy are lacking.

Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) solution intravesically had a 60% response rate in 1 study (versus 27% for placebo).22 The mechanism of action is unknown, but the solution may modulate the bladder immune response. Additional studies are pending.

Although their link to interstitial cystitis has not been proven, these foods are thought to be implicated and should be limited or avoided

ACIDIC FOODS

All alcoholic beverages

Apples

Apple juice

Cantaloupe

Carbonated drinks

Chilies/spicy foods

Citrus fruits (lemons, limes, oranges, etc)

Coffee

Cranberries

Grapes

Guava

Lemon juice

Peaches

Pineapples

Plums

Strawberries

Tea

Tomatoes

Vinegar

FOODS HIGH IN TYROSINE, TRYPTOPHAN, OR ASPARTATE

Aspartame

Avocado

Bananas

Beer

Brewer’s yeast

Canned figs

Champagne

Cheese

Chicken livers

Chocolate

Corned beef

Cranberries

Fava beans

Lima beans

Mayonnaise

Nuts

Onions

Pickled herring

Pineapple

Prunes

Raisins

Rye bread

Saccharine

Sour cream

Soy sauce

Wines

Yogurt

Vitamins buffered with aspartate

Adapted from You Don’t Have to Live with Cystitis! by Larrian Gillespie, MD (revised and updated 1996)

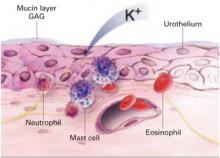

1. Altered bladder permeability

In interstitial cystitis, the protective glycosaminoglycan layer of the bladder epithelium may be deficient, increasing bladder permeability. Antiproliferative factor in the urine may impair the proliferation and repair of urothelium, increasing bladder permeability further.28 This breakdown allows potassium to penetrate the urothelium, stimulating pain receptors and causing an inflammatory response in the detrusor muscle.

Loss of the normal protective layer

In a normal bladder, the epithelium is protected by an ionic, hydrophilic, glycosaminoglycan (GAG) layer that serves as a barrier against urine, which is hyperosmolar and rich in acid and potassium. When the GAG layer is deficient, as it is thought to be in interstitial cystitis, bladder permeability increases, triggering an inflammatory response that inhibits repair of the GAG layer, creating a vicious cycle of exposure, inflammation, and pain.

2. Mast cell activation

Mast cell degranulation may cause or contribute to interstitial cystitis and produce its hallmark symptoms. Mast cells also may be activated in response to a noxious factor. These cells secrete histamine, prostaglandins, leukotrienes, cytokines, and chemotactic factors. Urine from women with interstitial cystitis contains histamine, histamine metabolites, and tryptase,29,30 and electron microscopy of bladder biopsies from affected women shows degranulating mast cells adjacent to sensory nerve fibers. When these fibers are stimulated, they release neuropeptides (such as substance P) and may promote inflammation by activating mast cells and nearby nerve terminals.31

3. Inflammation

Inflammation clearly plays a role in interstitial cystitis. Bladder biopsies reveal mild to severe inflammation, and the presence of T cells, B cells, plasma cells, neutrophils, eosinophils, and mast cells. Inflammatory mediators such as kallikrein, interleukin-6, interleukin-2 inhibitor, and neutrophil chemotactic factor are increased in the urine of individuals with the disease.

4. Autoimmunity

Clinical features of interstitial cystitis that mimic those of other autoimmune diseases include chronic symptoms that wax and wane; higher prevalence in women; immunological deposits in bladder biopsies with mononuclear cell infiltrates, which suggests the presence of bladder autoantigens; association with other autoimmune disorders such as Sjögren’s syndrome and lupus; and, in some cases, a positive response to steroids or other immunosuppressants.32

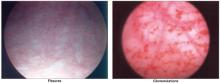

Glomerulations and fissures are telltale signs

When the bladder is distended under anesthesia, examination may reveal a pattern of fissures and glomerulations, which are hallmarks of interstitial cystitis. These findings are sometimes present in asymptomatic women as well, and do not always correlate with severity of symptoms.

5. Infection

Some experts have postulated that occult infection with fastidious organisms, fungi, or viruses plays a role in the development of interstitial cystitis. However, special cultures, serology, and electron microscopy have not shown any organisms consistently associated with the disease.33

The use of polymerase chain reaction techniques to test for bacterial DNA in bladder biopsies of patients with interstitial cystitis has yielded conflicting results.34,35 Infection may be the inciting event that injures the bladder epithelium, causing a cascade of inflammation.

6. Neurologic changes

Studies have revealed increased sympathetic nerve fiber density in the bladders of patients with interstitial cystitis.31,36 The disease may also be a type of reflex-sympathetic dystrophy with increased and abnormal spinal sympathetic activity. Butrick describes interstitial cystitis as a “visceral pain syndrome.”37 C-fibers (silent afferents) transmit pain when activated by a prolonged or noxious stimulus. This leads to neuroplastic changes that lower the threshold of nociceptive nerves, thus reducing the amount of stimulus needed to provoke pain (allodynia). Pelvic viscera share innervation, which may explain the association between

interstitial cystitis and irritable bowel syndrome and endometriosis. Interstitial cystitis is not limited to the bladder; it involves chronic neuropathic inflammation, afferent overactivity, and central sensitization. Increased pain perception may cause pelvic floor muscle instability, spasm, and hypertonic state.38