Public speaking fundamentals. Preparation: Tips that lead to a solid, engaging presentation

Although you may not be a seasoned public speaker—and may even feel some trepidation at the idea of speaking—several simple preparatory steps can bolster your confidence and help ensure a seamless, memorable talk

In this Article

- Preparing a presentation

- Your speech opening

- AV equipment and support

Ask about the meeting agenda. If a meal is to be served, will you be speaking beforehand? This is the least favorable time slot, as you are holding people hostage before they can eat. Our preference is to speak after the appetizer is served and the orders have been taken by the wait staff. This way, attendees are not starving and they have something to drink. You can assure the waiters they won’t be disturbing you, and you can ask them to avoid walking in front of the projector. Ideally, you should end your presentation before dessert arrives and use the remaining time to field questions.

We suggest that you prepare a handout to be distributed at the end of the program, not before. You want your audience focused on you and your slides as you are speaking. Tell the audience you will be providing a handout of your presentation, which will minimize note-taking during your talk.

Your speech opening

The first and last 30 seconds of any speech probably have the most impact.1 Give extra thought, time, and effort to your opening and closing remarks. Do not open with “Good evening, it is a pleasure to be here tonight.” That wastes precious seconds.

While opening a speech with a joke or funny story is the conventional wisdom, ask yourself1:

- Is my selection appropriate to the occasion and for this audience?

- Is it in good taste?

- Does it relate to me (my service) or to the event or the group? Does it support my topic or its key points?

A humorous story or inspirational vignette that relates to your topic or audience can grab the audience’s attention. If you feel that demands more presentation skill than you possess at the outset of your public-speaking career, give the audience what you know and what they most want to hear. You know the questions that you have heard most at cocktail receptions or professional society meetings. So, put the answers to those questions in your speech.

For example. A scientist working with a major corporation was preparing a speech for a lay audience. Since most of the audience did not know what scientists do, he offered the following analogy: “Being a scientist is like doing a jigsaw puzzle in a snowstorm at night...you don’t have all the pieces...and you don’t have the picture on the front of the box to work from.” You can say more with less.1

Your closing

The closing is an important aspect of your speech. Summarize the key elements to your presentation. If you are going to take questions, a good approach is to say, “Before my closing remarks, are there any questions?” Following the questions, finish with a takeaway message that ties into your theme.1

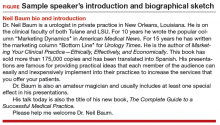

Prepare an autobiographical introduction

We suggest that you write your own introduction and e-mail it to the person who will be introducing you. Let them know it is a suggestion that they are welcome to modify. We have found that most emcees or meeting planners are delighted to have the introduction and will use it just as you have written it. Also bring hard copy with you; many emcees will have forgotten to download what you sent. The figure shows an example of the introduction that one of us (NHB) uses, and you are welcome to modify it for your own use.

Ask about and confirm audiovisual support

Ask the meeting planner ahead of time if they will be providing the computer, projector, and screen. And if, for instance, they will provide a projector but not a computer, make sure the computer you will bring is compatible with their projector. Also, you will probably not require a microphone for a small group, but if you are speaking in a loud restaurant, a portable microphone-speaker system may be helpful.

Arrive early at the program venue to make sure the computers, projector, screen placement, and seating arrangement are all in order. Nothing can sidetrack a speaker (even a seasoned one) like a problem with the computer or equipment setup—for example, your flash drive requiring a USB port cannot connect to the sponsor’s computer, or your program created on a Mac does not run on the sponsor’s PC.

Show time: Getting ready

Another benefit in arriving early, besides being able to check on the equipment, is the chance to greet the audience members as they enter. It is easier to speak to a group of friends than strangers. And if you can remember their names, you can call on them and ask their opinion or how they might manage a patient who has the condition you are discussing. You also could suggest to the meeting planner that name tags for attendees would be helpful.