Minimally Invasive Surgical Treatments for Obstructive Sleep Apnea

Surgery remains an option for patients who cannot tolerate positive airway pressure treatment but carries risks that must be considered.

Nasal expiratory positive end pressure (EPAP) devices may be helpful in treating OSA in some patients. These devices contain a mechanical valve with very low inspiratory resistance but high expiratory resistance. The device has an adhesive and is applied by the patient to create a seal. Exhalation causes a high expiratory resistance that splints the upper airway open. This increases the resistance of the airway to close on inspiration.7 An EPAP device is recommended for potential use in mild to moderate OSA for patients who either have an intolerance to CPAP therapy or have failed to respond to it.8

Finally, there are major surgeries performed by oral surgeons that can benefit some patients with OSA. One of these is maxillomandibular advancement (MMA). According to the AASM practice parameter: MMA “involves simultaneous advancement of the maxilla and mandible through sagittal split osteotomies. It provides enlargement of the retrolingual airway and some advancement of the retropalatal airway.”9 It is indicated as a surgical treatment for patients with severe OSA who are either unwilling or do not tolerate CPAP treatment. These individuals would not benefit from an oral appliance (recommended for mild to moderate OSA) or would find it undesirable.9

There is also stepwise or multilevel surgery (MLS) that can be performed. These include a number of combined procedures, which address multiple sites with narrowing in the upper airway. Frequently, MLS will consist of

2 phases: the first involves use of the uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP) procedure “and or genioglossus advancement and hyoid myotomy (GAHM). The second phase surgeries consist of utilizing maxillary and mandibular advancement osteotomy (MMO), offered to those failing Phase I surgeries.”9

OSA Surgical Procedures

Tracheostomies are first estimated to have been performed in 2000 BC.10 Performing a tracheostomy to bypass the upper airway was used in the 1960s and 1970s for the treatment of OSA and for many years was the only treatment available for people with Pickwickian syndrome (OHS) and nocturnal upper airway obstruction. The procedure was generally not tolerated or accepted by patients, even though it improved their quality of life and added to their life expectancy. Once CPAP treatment proved successful for OSA, tracheostomy has rarely been necessary.11

Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty surgery was introduced in 1981. The aim of this surgery is to decrease snoring and treat OSA by removing obstructive tissues, enlarging the cross-sectional portion of the upper airway, and bypassing the upper airway. Tissue that is removed includes the tonsils, uvula, and the distal portion of the soft palate.12

Woodson considers surgery for OSA to be the third-line of treatment. The first-line treatment would be CPAP therapy, and second-line therapy would include oral appliances to enlarge the airway or retain the tongue (if the individual has no dentition). The intent of surgery falls into 3 categories: curative, salvage, and ancillary.

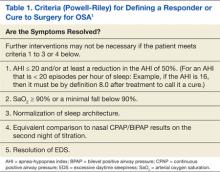

In a chronic disease such as OSA, “many may question whether a cure exists.” Instead of eliminating OSA, the curative intent is definitively to reduce symptoms and disease morbidity for long periods. The criteria for defining a responder or cure to surgery for OSA are found in Table 1.5

Surgery for salvage aims at treating patients who have failed CPAP therapy. Successful treatment with the intent of salvage can occur with a lessening of disease severity, including morbidity and mortality, but not necessarily totally eliminating the symptoms. Finally, ancillary surgery for OSA aims to combine a surgical procedure with the first-line therapy (positive pressure) to add an additional therapeutic benefit. The combination of CPAP and ancillary procedures may be of the most benefit to patients with OSA.5

As mentioned previously, the AASM has developed practice parameters for the treatment of OSA, including surgery. Desired outcomes of treatment for OSA include the resolution of symptoms and clinical signs, normalization of the quality of sleep, AHI, and levels of oxyhemoglobin saturation. It is recognized that normalization of the AHI may not reverse all the components of OSA, and up to 22% of patients continue to have residual hypersomnia with CPAP therapy.9

Despite this, most studies that show significant benefits in lowering cardiovascular risk, mortality rates, symptoms, and neurocognitive effects have also shown significant reductions in the AHI.9 Therefore, the AASM puts a high value on treating OSA with the goal of normalization of the AHI. There exists a lack of quality studies and good evidence regarding the effectiveness of surgical procedures of the upper airway as treatment for OSA. Despite this, the AASM recommendation is that “all reasonable treatment alternatives for OSA be discussed in a manner that allows the patient to make an informed decision.”9