Low-Carbohydrate and Ketogenic Dietary Patterns for Type 2 Diabetes Management

Background: Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) has been traditionally considered a chronic, progressive disease. Since 2017, guidelines from the US Department of Veterans Affairs and US Department of Defense have included low-carbohydrate (LC) dietary patterns in managing T2DM. Recently, carbohydrate reduction, including ketogenic diets, has gained renewed interest in the management and remission of T2DM.

Observations: This narrative review examines the evidence behind carbohydrate reduction in T2DM and a practical guide for clinicians starting patients on therapeutic LC diets. We present an illustrative case and provide practical approaches to prescribing a very LC ketogenic (< 50 g), LC (50-100 g), or a moderate LC (101-150 g) dietary plan and discuss adverse effects and management of LC diets. We provide a medication management and deprescription approach and discuss strategies to consider in conjunction with LC diets. As patients adopt LC diets, glycemia improves, and medications are deprescribed, hemoglobin A1c levels and fasting glucose may drop below the diagnostic threshold for T2DM. Remission of T2DM may occur with LC diets (hemoglobin A1c < 6.5% for ≥ 3 months without T2DM medications). Finally, we describe barriers and limitations to applying therapeutic carbohydrate reduction in a federal health care system.

Conclusions: The effective use of LC diets with close and intensive lifestyle counseling and a safe approach to medication management and deprescribing can improve glycemic control, reduce the overall need for insulin and medication and provide sustained weight loss. The efficacy and continuation of therapeutic carbohydrate reduction for patients with T2DM appears promising. Further research on LC diets, emerging strategies, and long-term effects on cardiometabolic risk factors, morbidity, and mortality will continue to inform practice.

Medications to Reduce or Discontinue

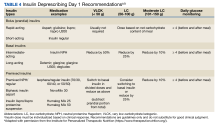

Medications that can cause hypoglycemia should be the first to be reduced or discontinued upon starting an LC diet, including bolus insulin (although a small amount may be needed to correct for high blood sugar), sulfonylureas, and meglitinides. Combination insulin should be stopped and changed to basal insulin to avoid the risk of hypoglycemia (see Table 4 for insulin deprescribing recommendations). The mechanism of action in preventing the breakdown of carbohydrates in the gastrointestinal tract makes the use of α-glucosidase inhibitors superfluous, and they can be discontinued, reducing pill burden and polypharmacy risks. Sodium-glucose transport protein 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) should be discontinued for patients on VLCK diets due to the risk of euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis. However, with LC and moderate LC plans, the SGLT2i may be used with caution as long as patients are made aware of ketoacidosis symptoms. To help prevent the risk of hypoglycemia, basal/long-acting insulin can be continued, but at a 50% reduced dose. Patients should closely monitor blood sugar to assess for appropriateness of dose reductions. While thiazolidinediones are not contraindicated, clinicians can consider discontinuation given both their penchant for inducing weight gain and their limited outcomes data.

Medications to Continue

Medications that pose minimal risk for hypoglycemia can be continued, including metformin, dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors, and glucagon-like peptide-1 agonists. However, even though these may pose a low risk of hypoglycemia, patients should still closely monitor their blood glucose so medications can be deprescribed as soon as safely and reasonably possible.

Other Medications

The improvement in metabolic health with the reduction of carbohydrates can render other classes of medications unnecessary or require adjustment. Patients should be counseled to monitor their blood pressure as significant and rapid improvements can occur. In the event of a systolic blood pressure of 100 to 110 mm Hg or signs of hypotension, down titration or discontinuation of antihypertensives should be initiated. Limited evidence exists on the preferred order of discontinuation but should be informed by other comorbidities, such as coronary artery disease and chronic kidney disease. Given an LC diet’s diuretic effect, tapering and stopping diuretics may be an option. Other medications requiring closer monitoring include lithium (can be affected by fluid and electrolyte shifts), warfarin (may alter vitamin K intake), valproate (which may be reduced), and zonisamide and topiramate (kidney stone risk).

Remission of T2DM with LC Diets

As patients adopt LC diets and medications are deprescribed and glycemia improves, HbA1c and fasting glucose levels may drop below the diagnostic threshold for T2DM.20 As new evidence emerges surrounding the management of T2DM from a lifestyle perspective, major health care organizations have acknowledged that T2DM is not necessarily an incurable, progressive disease, but rather a disease that can be reversed or put in remission.35-37 In 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) global report on diabetes acknowledged that T2DM reversal can be achieved via weight loss and calorie restriction.35

In 2021, a consensus statement from the ADA, the Endocrine Society, the EASD, and Diabetes UK defined T2DM remission as an HbA1c level < 6.5% for at least 3 months with no T2DM medications.36 Diabetes Australia also published a position statement in 2021 about T2DM remission.37 Like the WHO, Diabetes Australia acknowledged that remission of T2DM is possible following intensive dietary changes or bariatric surgery.37 Before the 2021 consensus statement, some experts argued that excluding metformin from the T2DM medication list may not be warranted since metformin has indications beyond T2DM. In this case, remission of T2DM could be defined as an HbA1c level < 6.5% for at least 3 months and on metformin or no T2DM medications.8