Acetaminophen as Renoprotective Treatment in a Patient With Severe Malaria

Background: Severe falciparum malaria with renal impairment carries a significant risk of poor outcomes, including death. Previous randomized controlled trials using acetaminophen as adjunctive treatment for malaria-associated renal failure have demonstrated improvements in renal function and kidney injury progression.

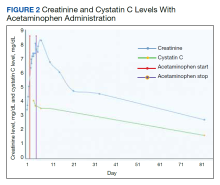

Case Presentation: A 50-year-old man with severe falciparum malaria presented with hemolytic anemia, oliguric acute kidney injury, nephrotic range proteinuria, and significant architectural changes on renal ultrasound. Treatment with oral acetaminophen 975 mg every 6 hours was based on the randomized controlled trial protocol to salvage his renal function and avoid dialysis. During the acetaminophen course, urine output and cystatin C level improved with only mild, asymptomatic elevations in aminotransferases that were corrected on follow-up. The patient recovered without requiring dialysis.

Conclusions: Acetaminophen’s potential to mitigate the oxidative damage of hemoproteins suggests its use as a treatment in severe malaria with renal impairment.

The patient received multiple boluses of IV isotonic fluids and a single maximum dose of atovaquone and proguanil before procurement of IV artesunate to manage the malaria. Good response with IV artesunate lowered parasitemia from a high at admission of 10.5% to 0.1% before transitioning to oral artemether and lumefantrine. Concomitantly, the patient’s oliguric renal failure continued to progress early during the hospital stay, and he consented to anticipated dialysis.

To halt progression of his renal injury, salvage renal function, and avoid dialysis, the nephrology team considered acetaminophen 975 mg tablets every 6 hours for 72 hours per the Plewes and colleagues randomized trial.5 The patient met the criteria for severe falciparum malaria per the inclusion criteria in the Plewes and colleagues study and was deemed eligible for acetaminophen-based adjunctive treatment. The patient discussed and considered both dialysis and a trial of acetaminophen with the nephrology team, and he understood all the associated risks and benefits, including liver failure. The patient agreed to a trial of acetaminophen with close monitoring of his liver function.

Before starting acetaminophen, the patient’s aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels both measured 53 IU/L or 1.3 times the upper limit of normal (Figure 2).

Discussion

AKI in malaria predominantly occurs with P falciparum infection and represents a significant independent factor in determining morbidity and mortality in adults with severe malaria.8 In severe malaria, any hemodynamic compromise likely contributes to the development of acute tubular necrosis (ATN) with insensible losses and poor intake decreasing renal perfusion.8 Direct tubular injury from hemoglobinuria or less commonly myoglobinuria from concomitant rhabdomyolysis may also drive malarial AKI.8 In addition, proposed mechanisms explaining the pathogenesis of malarial AKI include ATN secondary to disruptions in renal microvasculature, immune dysregulation with proinflammatory reactions within the kidneys, and metabolic disturbances.8 Oxidate tubular damage caused by the release of cell-free hemoglobin during red blood cell hemolysis represents 1 form of metabolic derangement possibly responsible for renal impairment.8 Acetaminophen administration may help mitigate this oxidative stress, especially in cases of significant hemolysis.5