Engaging Veterans With Serious Mental Illness in Primary Care

Background: Veterans with serious mental illness (SMI) are at substantial risk for premature mortality. Engagement in primary care can mitigate these mortality risks. However, veterans with SMI often become disengaged from primary care. The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) measures and reports at VA facilities primary care engagement among enrolled veterans with SMI. This quarterly metric enables VA facilities to identify targets for quality improvement and track their progress. To inform quality improvement at our VA facility, we sought to identify promising practices for supporting engagement in primary care among veterans with SMI.

Methods: We conducted semistructured telephone interviews from May 2019 through July 2019 with a purposeful sample of key informants at VA facilities with high levels of engagement in primary care among veterans with SMI. All interviews were recorded, summarized using a structured template, and summaries placed into a matrix. An interdisciplinary team reviewed and discussed matrices to identify and build consensus around findings.

Results: We interviewed 18 key informants from 11 VA facilities. The strategies used to engage veterans with SMI fell into 2 general categories: targeted outreach and routine practices. Targeted outreach included proactive, deliberate, systematic approaches for identifying and contacting veterans with SMI who are at risk of disengaging from care. In targeted outreach, veterans were identified and prioritized for outreach independent of any visits with mental health or other VA services. Routine practices included activities embedded in regular clinical workflows at the time of veterans’ mental health visits, assessing, and connecting/reconnecting veterans with SMI into primary care. In addition, we identified extensive formal and informal ties between mental health and primary care that facilitated engaging veterans with SMI in primary care.

Conclusions: VA facilities with high levels of primary care engagement among veterans with SMI used extensive engagement strategies, including a diverse array of targeted outreach and routine practices. Intentionally designed organizational structures and processes and facilitating extensive formal and informal ties between mental health and primary care teams supported these efforts. Additional organizational cultural factors were especially relevant to routine practice strategies. The practices we identified should be evaluated empirically for their effects on establishing and maintaining engagement in primary care among veterans with SMI.

Interview audio recordings were used to generate detailed notes (AG). Structured summaries were prepared from these notes, using a template based on the interview guide. We organized these summaries into matrices for analysis, grouping summarized points by interview domains to facilitate comparison across interviews.10-11 Our team reviewed and discussed the matrices, and iteratively identified and defined themes to identify the common engagement approaches and the nature of the connections between mental health and primary care. To ensure rigor, findings were checked by the senior qualitative lead (JM).

Results

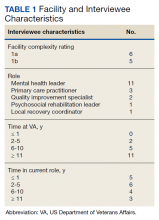

The median SMI engagement score—defined as the proportion of veterans with SMI who have had a primary care visit in the prior 12 months and who have an assigned PCP—was 75.6% across 1a and 1b VA facilities. We identified 16 VA facilities that had a median or higher score and more than 1000 enrolled veterans experiencing homelessness. From these16 facilities, we emailed 31 potential interviewees, 14 of whom were identified from a VA database and 17 referred by other interviewees. In total, we interviewed 18 key informants across 11 (69%) facilities, including chiefs of psychology and mental health services, PCPs with mental health expertise, QI specialists, a psychosocial rehabilitation leader, and a local recovery coordinator, who helps veterans with SMI access recovery-oriented services. Characteristics of the facilities and interviewees are shown in Table 1. Interviews lasted a mean 35 (range, 26-50) minutes.

Engagement Approaches

The strategies used to engage veterans with SMI were heterogenous, with no single strategy common across all facilities. However, we identified 2 categories of engagement approaches: targeted outreach and routine practices.

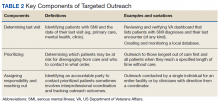

Targeted outreach strategies included deliberate, systematic approaches to reach veterans with SMI outside of regularly scheduled visits. These strategies were designed to be proactive, often prioritizing veterans at risk of disengaging from care. Designated VA care team members identified and reached out to veterans well before 12 months had passed since their prior visit (the VA definition of disengagement from care); visits included any care at VA, including, but not exclusively, primary care. Table 2 describes the key components of targeted outreach strategies: (1) identifying veterans’ last visit; (2) prioritizing which veterans to outreach to; and (3) assigning responsibility and reaching out. A key defining feature of targeted outreach is that veterans were identified and prioritized for outreach independent from any visits with mental health or other VA services.

In identifying veterans at risk for disengagement, a designated employee in mental health or primary care (eg, local recovery coordinator) reviewed a VA dashboard or locally developed report that identified veterans who have not engaged in care for several months. This process was repeated regularly. The designated employee either contacted those veterans directly or coordinated with other clinicians and support staff. When possible, a clinician or nurse with an existing relationship with the veteran would call them. If no such relationship existed, an administrative staff member made a cold call, sometimes accompanied by mailed outreach materials.

Routine practices were business-as-usual activities embedded in regular clinical workflows that facilitated engagement or reengagement of veterans with SMI in care. Of note, and in contrast to targeted outreach, these activities were tied to veteran visits with mental health practitioners. These practices were typically described as being at least as important as targeted outreach efforts. For example, during mental health visits, clinicians routinely checked the VA electronic health record to assess whether veterans had an assigned primary care team. If not, they would contact the primary care service to refer the patient for a primary care visit and assignment. If the patient already had a primary care team assigned, the mental health practitioner checked for recent primary care visits. If none were evident, the mental health practitioner might email the assigned PCP or contact them via instant message.

At some facilities, mental health support staff were able to directly schedule primary care appointments, which was identified as an important enabling factor in promoting mental health patient engagement in primary care. Some interviewees seemed to take for granted the idea that mental health practitioners would help engage patients in primary care—suggesting that these practices had perhaps become a cultural norm within their facility. However, some interviewees identified clear strategies for making these practices a consistent part of care—for example, by designing a protocol for initial mental health assessments to include a routine check for primary care engagement.

Mental Health/Primary Care Connections

Interviewees characterized the nature of the connections between mental health and primary care at their facilities. Nearly all interviewees described that their medical centers had extensive ties, formal and informal, between mental health and primary care.

Formal ties may include the reverse integration care model, in which primary care services are embedded in mental health settings. Interviewees at sites with programs based on this model noted that these programs enabled warm hand-offs from mental health to primary care and suggested that it can foster integration between primary care and mental health care for patients with SMI. However, the size, scope, and structure of these programs varied, sometimes serving a small proportion of a facility’s population of SMI patients. Other examples of formal ties included written agreements, establishing frequent, regular meetings between mental health and primary care leadership and front-line staff, and giving mental health clerks the ability to directly schedule primary care appointments.