Stories of the Heart: Illness Narratives of Veterans Living With Heart Failure

Background: Illness narratives for veterans living with heart failure (HF) have been largely unexplored, yet HF is a significant and impactful illness affecting the lives of many veterans.

Methods: This study used narrative inquiry to explore the domains of psychosocial adjustments using the model of adjustment to illness, including self-schema, world schema, and meaning.

Results: Five illness narratives of veterans living with HF were cocreated and explored domains which were found across all the narratives explored in this study. Emergent themes included: uniqueness of the veteran experience and the social, historical, and cultural context of narrator and researcher.

Conclusions: Veterans living with HF are a unique population who experience changes in their self-schema, world schema, and meaning through their illness experience. These findings have important implications for interdisciplinary health care research and clinical practice, providing important insight into how people live with chronic illness.

Narrative Analysis

Riessman described general steps to conduct narrative analysis, including transcription, narrative clean-up, consideration of contextual factors, exploration of thematic threads, consideration of larger social narratives, and positioning.12 The first author read transcripts while listening to the audio recordings to ensure accuracy. With narrative clean-up each narrative was organized to cocreate overall meaning, changed to protect anonymity, and refined to only include the illness narrative. For example, if a narrator told a story about childhood and then later in the interview remembered another detail to add to their story, narrative clean-up reordered events to make cohesive sense of the story. Demographic, historical, cultural, and social contexts of both the narrator and audience were reflected on during analysis to explore how these components may have shaped and influenced cocreation. Context was also considered within the larger VA setting.

Emergent themes were explored for convergence, divergence, and points of tension within and across each narrative. Larger social narratives were also considered for their influence on possible inclusion/exclusion of experience, such as how gender identity may have influenced study participants’ descriptions of their roles in social systems. These themes and narratives were then shared with our team, and we worked through decision points during the analysis process and discussed interpretation of the data to reach consensus.

Results

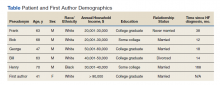

Five veterans living with HF were recruited and consented to participate in the study. Demographics of the participants and first author are included in the Table. Five illness narratives were cocreated, entitled: Blame the Cheese: Frank’s Illness Narrative; Love is Love: Bob’s Illness Narrative; The Brighter Things in Life is My Family: George’s Illness Narrative; We Never Know When Our Time is Coming: Bill’s Illness Narrative; and A Dream Deferred: Henry’s Illness Narrative.

Each narrative was explored focusing on the domains of the model of adjustment to illness. An emergent theme was also identified with multiple subthemes: being a veteran is unique. Related subthemes included: financial benefits, intersectionality of government and health care, the intersectionality of masculinity and military service, and the dichotomy of military experience.

The search for meaning creation after the experience of chronic illness emerged across interviews. One example of meaning creation was in Frank's illness narrative. Frank was unsure why he got HF: “Probably because I ate too much cheese…I mean, that’s gotta be it. It can’t be anything else.” By tying HF to his diet, he found meaning through his health behaviors.

Model of Adjustment to Illness

The narratives illustrate components of the model of adjustment to illness and describe how each of the participants either shifted their self-schema and world schema or reinforced their previously established schemas. It also demonstrates how people use narratives to create meaning and illness understanding from their illness experience, reflecting, and emphasizing different parts creating meaning from their experience.

A commonality across the narratives was a shift in self-schema, including the shift from being a provider to being reliant on others. In accordance with the dominant social narrative around men as providers, each narrator talked about their identity as a provider for themselves and their families. Often keeping their provider identity required modifications of the definition, from physical abilities and employment to financial security and stability. George made all his health care decisions based on his goal of providing for his family and protecting them from having to care for him: “I’m always thinking about the future, always trying to figure out how my family, if something should happen to me, how my family would cope, and how my family would be able to support themselves.” Bob’s health care goals were to stay alive long enough for his wife to get financial benefits as a surviving spouse: “That’s why I’m trying to make everything for her, you know. I’m not worried about myself. I’m not. Her I am, you know. And love is love.” Both of their health care decisions are shaped by their identity as a provider shifting to financial support.

Some narrators changed the way they saw their world, or world schema, while others felt their illness experience just reinforced the way they had already experienced the world. Frank was able to reprioritize what was important to him after his diagnosis and accept his own mortality: “I might as well chill out, no more stress, and just enjoy things ’cause you could die…” For Henry, getting HF was only part of the experience of systemic oppression that had impacted his and his family’s lives for generations. He saw how his oppression by the military and US government led to his father’s exposure to chemicals that Henry believed he inherited and caused his illness. Henry’s illness experience reinforced his distrust in the institutions that were oppressed him and his family.