A Step Toward Health Equity for Veterans: Evidence Supports Removing Race From Kidney Function Calculations

Background: The practice of race-based medicine fails to recognize that race cannot be used as a proxy for genetic ancestry and that racial and ethnic categories are complex sociopolitical constructs without biological basis. Clinical algorithms and equations that incorporate race modifiers and are currently considered standard for diagnosis and management of disease are appropriately being scrutinized for lack of biological plausibility and their role in exacerbating health inequities. In this paper, we review the history, evidence, and implications of using a Black race coefficient when calculating estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) in the diagnosis and management of kidney disease.

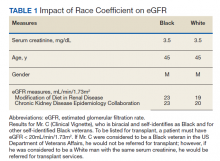

Observations: Currently, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) uses the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equation for eGFR. This equation includes a Black race coefficient that results in an eGFR that is 21% higher for a Black patient when compared with a patient of any other race. The rationale for the inclusion of this coefficient is based on racist science that incorrectly assumes race as a proxy for genetic ancestry. Multiple studies across diverse Black populations demonstrate that the application of a race coefficient in kidney function estimation equations is inferior when compared with the race-neutral option. Furthermore, the most utilized eGFR equations are biased and imprecise. Because eGFR is the primary diagnostic method for detecting and managing kidney disease, preventing its progression, planning for dialysis, and evaluating for transplantation, it is vital that eGFR be as accurate, precise, and equitable as possible.

Conclusions: The incorporation of a race coefficient in kidney estimation equations lacks biological plausibility and its use exacerbates kidney health disparities. Until a better method to estimate kidney function becomes available, a race-neutral option for current estimation equations should be applied for all patients.

Clinical Consequences of Race Coefficient Use

The use of a race coefficient in these estimation equations causes adverse clinical outcomes. In early stages of CKD, overestimation of eGFR using the race coefficient can cause an under-recognition of CKD, and can lead to delays in diagnosis and failure to implement measures to slow its progression, such as minimizing drug-related nephrotoxic injury and iatrogenic acute kidney injury. Consequently, a patient with an overestimated eGFR may suffer an accelerated progression to ESKD and premature mortality from cardiovascular disease.23

In advanced CKD stages, eGFR overestimation may result in delayed referral to a nephrologist (recommended at eGFR < 30mL/min/1.73 m2), nutrition counseling, renal replacement therapy education, timely referral for renal replacement therapy access placement, and transplant evaluation (can be listed when eGFR < 20 mL/min/1.73 m2).16,24,25

In the Clinical Vignette, it is clear from the information presented that Mr. C’s concerns are well-founded. Table 1 presents the impact on eGFR caused by the race coefficient using the MDRD and CKD-EPI equations. In many VA systems, this overestimation would prevent him from being referred for a kidney transplant at this visit, thereby perpetuating racial health disparities in kidney transplantation.

Concerns About Removal of Race From eGFR Calculations

Opponents of removing the race coefficient assert that a lower eGFR will preclude some patients from qualifying for medications such as metformin and certain anticoagulants, or that it may result in subtherapeutic dosing of drugs such as antibiotics and chemotherapeutic agents.26 These recommendations are in place for patient safety, so conversely maintaining the race coefficient and overestimating eGFR will expose some patients to medication toxicity. Another fear is that lower eGFRs will have the unintended consequence of limiting the kidney donor pool. However, this can be prevented by following current guidelines to use mGFR in settings where accurate GFR is imperative.16 Additionally, some nephrologists have expressed concern that diagnosing more patients with advanced stages of CKD will result in inappropriately early initiation of dialysis. Again, this risk can be mitigated by ensuring that nephrologists consider multiple clinical factors and data points, not simply eGFR when deciding to initiate dialysis. Also, an increase in referrals to nephrology may occur when the race coefficient is removed and increased wait times at some VA medical centers could be a concern. An increase in appropriate referrals would show that removing the race coefficient was having its intended effect—more veterans with advanced CKD being seen by nephrologists.

When considering the lack of biological plausibility, inaccuracy, and the clinical harms associated with the use of the race coefficient in eGFR calculations, the benefits of removing the race coefficient from eGFR calculations within the VA far outweigh any potential risks.

A Call for Equity

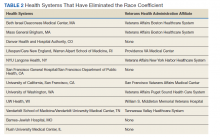

The National Conversation on Race and eGFR

To advance health equity, members of the medical community have advocated for the removal of the race coefficient from eGFR calculations for years. Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center was the first establishment to institute this change in 2017. Since then, many health systems across the country that are affiliated with Veterans Health Administration (VHA) medical centers have removed the race coefficient from eGFR equations (Table 2). Many other hospital systems are contemplating this change.