Long-Term Oxygen Therapy and Risk of Fire-Related Events

Introduction: Two large major trials showed that long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT) improved mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and hypoxemia. Although oxygen accelerates combustion and is an obvious fire hazard, LTOT has traditionally been prescribed to veterans who are actively smoking.

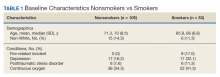

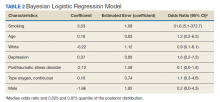

Methods: We conducted a retrospective chart review of all veterans with COPD at a single center who were prescribed new LTOT between October 2010 and September 2015. Of the 158 patients who met the study criteria, 152 were male. Bayesian logistic regression was used to model the outcome variable fire-related incident with the predictors smoking status, age, race, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and type of oxygen used.

Results: The mean age of the 158 patients with COPD in the study was 71.3 years in nonsmokers and 65.9 years in smokers. The model-estimated odds (SD) of a fire-related incident occurring in a smoker were 31.6 (5.1-372.7) times the odds of a fire-related incident occurring in a nonsmoker.

Conclusions: Patients who smoke and remain on LTOT put themselves at greater risk of having a fire-related incident than do nonsmokers.

Results

The mean age for the 158 included patients was 71.3 years in nonsmokers and 65.9 years in smokers. Fifty-three of the included patients were active smokers when LTOT was initiated. Nine veterans had fire-related incidents during the study period. All 9 patients were actively smoking (about 17%) at the time of the fire incidents. There were no deaths, and 5 patients required hospitalization due to facial burns resulting from the fire-related incidents. Our study focused on 5 baseline characteristics in our population (Table 1). After gathering data, our group inferred that these characteristics had a potential relationship to fire-related incidents compared with other variables that were studied. Future studies could look at other patient characteristics that may be linked to fire-related incidents in patients on LTOT. For example, not having PTSD also perfectly predicts fire-related incidents in our data (ie, none of the participants who had fire-related incidents had PTSD). Although this finding was not within the 95% confidence interval (CI) in the model, it does show that care must be taken when interpreting effects from small samples (Table 2). The modelestimated odds of a fire-related incident occurring in a smoker were 31.6 (5.1-372.7) times more likely than were the odds of a firerelated incident occurring in a nonsmoker, holding all other predictors at their reference level; 95% CI for the odds ratios for all other predictors in the model included a value of 1.

Discussion

This study showed evidence of increased odds of fire-related events in actively smoking patients receiving LTOT compared with patients who do not actively smoke while attempting to adjust for potential confounders. Of the 9 patients who had fire events, 5 required hospitalization for burns.

A similar retrospective cohort study by Sharma and colleagues in 2015 demonstrated an increased risk of burn-related injury when on LTOT but reiterated that the benefit of oxygen outweighs the risk of burn-related injury in patients requiring oxygen therapy.12 Interestingly, Sharma and colleagues were unable to identify smoking status for the patients studied but further identified factors associated with burn injury to include male sex, low socioeconomic status, oxygen therapy use, and ≥ 3 comorbidities. The study’s conclusion recommended continued education by health care professionals (HCPs) to their patients on LTOT regarding potential for burn injury. In the same vein, the VA National Center for Ethics in Health Care noted that “clinicians should familiarize themselves with the risks and benefits of LTOT; should inform their patients of the risks and benefits without exaggerating the risk associated with smoking; avoid undue coercion inherent in the clinician’s ability to withdraw LTOT; reduce the risk to the greatest degree possible; and consider termination of LTOT in very extreme cases and in consultation with a multidisciplinary committee.”13

This statement is in contrast to the guidelines and policies of other countries, such as Sweden, where smoking is a direct contraindication for prescription of oxygen therapy, or in Australia and New Zealand, where the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand oxygen therapy guidelines recommend against prescription of LTOT, citing “increased fire risk and the probability that the poorer prognosis conferred by smoking will offset treatment benefit.”6,14

The prevalence of oxygen therapy introduces the potential for fire-related incidents with subsequent injury requiring medical care. There are few studies regarding home oxygen fire in the US due to the lack of a uniform reporting system. One study by Wendling and Pelletier analyzed deaths in Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Oklahoma between 2000 and 2007 and found 38 deaths directly attributable to home oxygen fires as a result of smoking.15 Further, the Consumer Product Safety Commission’s National Electronic Injury Surveillance System between 2003 and 2006 attributed 1,190 thermal burns related to home oxygen fires; the majority of which were ignited by tobacco smoking.15 The Swedish National Register of Respiratory Failure (Swedevox) published prospective population-based, consecutive cohort study that collected data over 17 years and evaluated the risk of fire-related incident in those on LTOT. Of the 12,497 patients sampled, 17 had a burn injury and 2 patients died. The low incidence of burn injury on LTOT was attributed to the strict guidelines instituted in Sweden for doctors to avoid prescribing LTOT to actively smoking patients.6 A follow-up study by Tanash and colleagues compared the risk of burn injury in each country, respectively. The results found an increased number of burn injuries in those on oxygen therapy in Denmark, a country with fewer restrictions on smoking compared with those of Sweden.7 Similarly, our results showed that the rate of fire and burn injuries was exclusively among veterans who were active smokers. All patients who were prescribed oxygen therapy at CTVHCS received counseling and signed Home Safety Agreements. Despite following the recommendations set forth by the VA on counseling, extensive harm reduction techniques, and close follow-up, we found there was still a high incidence of fires in veterans with COPD on LTOT who continue to smoke.

The findings from our study concur with those previously published regarding the risk of home oxygen fire and concomitant smoking, supporting the idea for more regulated and concrete guidelines for prescribing LTOT to those requiring it.8

Limitations

The major limitation was the small sample size of our study. Another limitation was that our study population is predominantly male as is common in veteran cohorts. In fiscal year 2016, the veteran population of Texas was 1,434,361 males and 168,967 females.16 According to Franklin and colleagues, HCPs noticed an increase use of long-term oxygen among women compared with that of men.17

Conclusions

Our study showed an increased odds of firerelated incidents of patients while on LTOT, strengthening the argument that even with extensive education, those who smoke and are on LTOT continue to put themselves at risk of a fire-related incident. This finding stresses the importance of continuing patient education on the importance of smoking cessation prior to administration of LTOT or avoiding fire hazards while on LTOT. Further research into LTOT and fire hazards could help in implementing a more structured approval process for patients who want to obtain LTOT. We propose further studies evaluating risk factors for the incidence of fire events among patients prescribed LTOT. A growing and aging population with a need for LTOT necessitates examination of oxygen safe prescribing.