Healthy Aging Project-Brain: A Psychoeducational and Motivational Group for Older Veterans

Introduction: Positive health behaviors can promote brain health with age. Although healthy lifestyle factors are often encouraged by health care providers, many older adults experience difficulty incorporating these into their daily life.

Methods: To address this gap, we developed a novel health education and implementation group for older veterans (aged > 50 years). The primary objectives of this group were to provide psychoeducation about the link between behaviors and brain health, increase personal awareness of specific health behaviors, and promote behavior change through individualized goal setting, monitoring, and support. Based on input from medical providers, group content targeted behaviors known to support cognitive functioning: physical activity, sleep, cognitive stimulation, and social engagement.

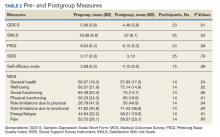

Results: Thirty-one veterans participated in six 90-minute weekly classes and attended 5 of the 6 groups on average. The average age for the predominantly male (90%) and white (70%) group was 71 years. Qualitative feedback indicated high satisfaction and increased awareness of health behaviors. Results of paired samples t tests comparing baseline to posttreatment self-report measures revealed a significant decline in depressive symptoms ( P = .01) and increases in satisfaction with life ( P = .003) and self-efficacy ( P = .008).

Conclusions: This development project showed evidence of increased awareness of health behaviors and improved mood. Expanded data collection will strengthen power and generalizability of results (increase sample diversity). It will also allow us to examine moderating factors, such as perceived self-efficacy, on outcomes.

At the start of the class, the mean (SD) reports of participants were mild depressive symptoms 5.96 (3.8) on the GDS scale, moderate levels of self-efficacy 3.69 (0.5) on the self-efficacy scale, and moderate levels of satisfaction with life 18.08 (6.8) on the SWLS scale (Table 2). Data from 25 of 31 veterans who completed both pregroup and postgroup surveys were analyzed and paired samples t tests without corrections indicated a reduction in depressive symptoms (P = .01), improved self-efficacy (P = .08), and improved satisfaction with life (P = .03). There were no significant differences in self-reported sleep quality or perceived social support from pregroup to postgroup evaluations. Because the sample size was smaller for the MOS-36, which was not used until group 3, and the subscales are composed of few items each, we conducted exploratory analyses of the 8 MOS-36 subscales and found that well-being, physical functioning, role limitations due to physical and emotional functioning, and energy/fatigue significantly improved over time (Ps < .04).

Twenty-eight veterans provided written feedback following the final session. Qualitative feedback received at the completion of the group focused on participants’ desire for increased number of classes, longer sessions (eg, 2 participants recommended lengthening the group to 2 hours), and integrating mindfulness-based activities into each class. Participants rated themselves somewhat likely to very likely to recommend this group to other veterans (mean, 2.9 [SD, 0.4]).

Discussion

The ability and need to promote brain health with age is an emerging priority as our aging population grows. A growing body of evidence supports the role of health behaviors in healthy brain aging. Education and skills training in a group setting provides a supportive, cost-effective approach for increasing overall health in aging adults. Yet older adults are statistically less likely to engage in these behaviors on a regular basis. The current investigation provides preliminary support for a model of care that uses a comprehensive, experiential psychoeducational approach to facilitate behavior change in older adults. Our aim was to develop and implement an intervention that was feasible and acceptable to our older veterans and to determine any positive outcomes/preliminary effects on overall health and well-being.

Participants indicated that they enjoyed the group, learned new skills (per participant feedback and facilitator observation), and experienced improvements in mood, self-efficacy, and life satisfaction. Given the participants’ positive response to the group and its content, as well as continued referrals by HCPs to this group and low difficulty with ongoing recruitment, this program was deemed both feasible and acceptable in our veteran health care setting. Questions remain about the extent to which participants modified their health behaviors given that we did not collect objective measurements of behaviors (eg, time spent exercising), the duration of behavior change (ie, how long during and after the group were behaviors maintained), and the role of premorbid or concurrent characteristics that may moderate the effect of the intervention on health-related outcomes (eg, sleep quality, perceived social support, overall functioning, concurrent interventions, medications).