Steroid-Induced Sleep Disturbance and Delirium: A Focused Review for Critically Ill Patients

Objective: Insomnia and delirium have gained much attention since the publication of recent guidelines for the management in critically ill adults. Neurologic effects such as sleep disturbance, psychosis, and delirium are commonly cited adverse effects (AEs) of corticosteroids. Steroid use is considered a modifiable risk factor in intensive care unit patients; however, reported mechanisms are often lacking. This focused review will specifically evaluate the effects of steroids on sleep deprivation, psychosis, delirium, and what is known about these effects in a critically ill population.

Observations: The medical literature proposes 3 pathways primarily responsible for neurocognitive AEs of steroids: behavior changes through modification of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, changes in natural sleep-wake cycles, and hyperarousal caused by modification in neuroinhibitory pathways. Initial search fields produced 285 articles. Case reports, reviews, letters, and articles pertaining to primary care or palliative populations were excluded, leaving 8 relevant articles for inclusion.

Conclusions: Although steroid therapy often cannot be altered in the critically ill population, research showed that steroid overuse is common in intensive care units. Minimizing dosage and duration are important ways clinicians can mitigate AEs.

Mitigating Effects

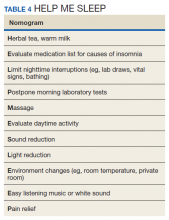

Although steroid therapy often cannot be altered in the critically ill population, research showed that steroid overuse is common in ICUs.56,57 Minimizing dosage and duration are important ways clinicians can mitigate unwanted effects. CNS AEs seen with steroids often can be reversed once therapy is discontinued. Avoiding split-dose administration has been proposed given the natural diurnal production of cortisol.58 A review by Flaherty discusses the importance of avoiding pharmacologic agents in hospitalized older patients if possible due to known risks (falls, dependency, hip fractures, rebound insomnia, and risk of delirium) and provides a HELP ME SLEEP nomogram for nonpharmacologic interventions in hospitalized patients (Table 4).59

Historically, lithium has been recommended for steroid-induced mania with chronic steroid use; however, given the large volume and electrolyte shifts seen in critically ill patients, this may not be a viable option. Antidepressants, especially tricyclics, should generally be avoided in steroid-induced psychosis as these may exacerbate symptoms. If symptoms are severe, either typical (haloperidol) or atypical (olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone) antipsychotics have been used with success.60 Given the known depletion of serum melatonin levels, melatonin supplements are an attractive and relatively safe option for steroid-induced insomnia; however, there are no robust studies specifically aimed at this intervention for this population.

Conclusions

With known, multimodal foci driving sleep impairment in ICU patients, PADIS guidelines recommend myriad interventions for improvement. Recommendations include noise and light reduction with earplugs and/or eyeshades to improve sleep quality. Nocturnal assist-control ventilation may improve sleep quality in ventilated patients. Finally, the development of institutional protocols for promoting sleep quality in ICU patients is recommended.17