Quality of Care for Veterans With In-Hospital Stroke

For our analysis, patients were stratified into 2 categories: patients admitted to the hospital for another diagnosis who developed an IHS, and patients presenting with stroke to the ED. We excluded patients transferred from other facilities. We then compared the demographic and clinical features of the 2 groups as well as eligibility and passing rates for each of the 11 QIs. Patients were recorded as eligible if they did not have any clinical contraindication to receiving the assessment or intervention measured by the quality metric. Passing rates were defined by the presence of clear documentation in the patient record that the quality metric was met or fulfilled. Comparisons were made using nonparametric Mann-Whitney U tests and chi-square tests. All tests were performed at α .05 level.

Results

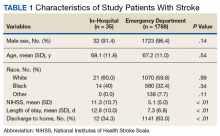

A total of 1823 patients were included in this analysis: 35 IHS and 1788 ED strokes. The 2 groups did not differ with respect to age, race, or sex (Table 1). Patients with IHS had higher stroke severity (mean NIHSS 11.3 vs 5.1, P <.01) and longer length of stay than did ED patients with stroke (mean 12.8 vs 7.3 days, P < .01). Patients with IHS also were less likely to be discharged home when compared with ED patients with stroke (34.3% vs 63.8%, P < .01).

Table 2 summarizes our findings on eligibility and passing rates for the 11 QIs. For acute care metrics, we found that stroke severity documentation rates did not differ but were low for each patient group (51% vs 48%, P = .07). Patients with IHS were more likely to be eligible for IV tissue plasminogen activator (tPA; P < .01) although utilization rates did not differ. Only 2% of ED patients met eligibility criteria to receive tPA (36 of 1788), and among these patients only 16 actually received the drug. By comparison, 5 of 6 of eligible patients with IHS received tPA. Rates of dysphagia screening also were low for both groups, and patients with IHS were less likely to receive this screen prior to initiation of oral intake than were ED patients with stroke (27% vs 50%, P = .01).

Beyond the acute period, we found that patients with IHS were less likely than were ED patients with stroke to be eligible to receive antithrombotic therapy by 2 days after their initial stroke evaluation (74% vs 96%, P < .01), although treatment rates were similar between the 2 groups (P = .99). In patients with documented atrial fibrillation, initiation of anticoagulation therapy also did not differ (P = .99). The 2 groups were similar with respect to initiation of venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis (P = .596) and evaluation for rehabilitation needs (P = .42). Although rates of smoking cessation counseling and stroke education prior to discharge did not differ, overall rates of stroke education were very low for both groups (25% vs 36%, P = .55).

Similar to initiation of antithrombotic therapy in the hospital, we found lower rates of eligibility to receive antithrombotic therapy on discharge in the IHS group when compared with the ED group (77% vs 93%, P = .04). However, actual treatment initiation rates did not differ (P = .12). Use of lipid-lowering agents was similar for the 2 groups (P = .12).