Driving-Related Coping Thoughts in Post-9/11 Combat Veterans With and Without Comorbid PTSD and TBI

Assessment

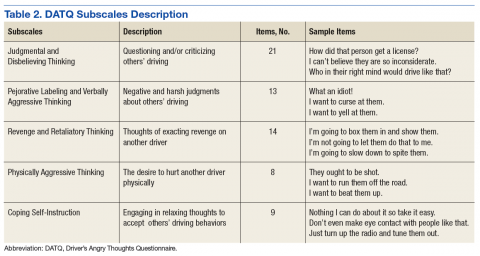

All participants completed a battery of questionnaires, including the Driver’s Angry Thoughts Questionnaire (DATQ).23 The DATQ was used to investigate the specific thoughts that veterans experienced while driving.23 Participants indicated on a Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (all the time) how often they experienced any of 65 thoughts while driving. Each item was categorized into 1 of 5 distinct subscales (Table 2). A frequency score was generated for each of the 5 subscales. Each subscale had good internal consistency and convergent, divergent, and predictive validity. The Coping Self-Instruction subscale, which is defined as engaging in relaxing thoughts to accept others’ driving behaviors, was of primary interest. It is a 9-item scale (frequency score can range from 9 to 45) with good reliability (α = .83).23

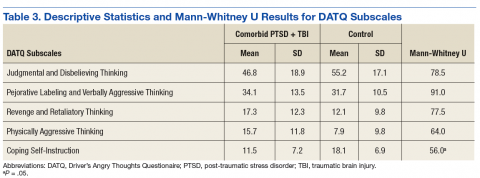

Given the small and unequal sample sizes, nonparametric independent samples Mann-Whitney U-tests were selected to compare frequency of driving-related thoughts across veterans with comorbid PTSD and TBI and those of veterans without either PTSD or TBI.

Results

Descriptive statistics and results for each DATQ subscale are reported in Table 3. Group comparisons revealed that veterans with comorbid PTSD and TBI endorsed statistically significantly fewer coping self-instruction thoughts while driving (M = 11.5, SD = 7.2) than did combat veterans without either PTSD or TBI (M = 18.1, SD = 6.9; U = 56.0, P = .05). Conversely, frequency of angry thoughts were statistically significant in their difference as a function of PTSD or TBI diagnostic status.

Discussion

While driving, veterans with PTSD or TBI endorsed statistically significantly fewer coping self-instruction thoughts than did veterans without either PTSD or TBI. Prior research suggests that veterans with PTSD or TBI experience greater anxiety than do veterans without either condition while driving.2,3 Taken together, this suggests that veterans with PTSD or TBI may lack efficient cognitive coping strategies related to the anxiety they experience while driving. Furthermore, the groups did not significantly differ in frequency of angry thoughts behind the wheel. This result was expected based on prior analyses that suggested that veterans with and without PTSD or TBI endorsed feelings of aggression, impatience, and frustration while driving at similar frequencies.3

Because all veterans in the current sample were exposed to combat, these results help to parse out the unique contribution of PTSD and TBI diagnoses on driving in civilian environments. Exposure to combat plus diagnoses of PTSD or TBI may be related to veterans’ ability to cope with typical driving situations at home. In the context of prior literature, results suggest that veterans with PTSD or TBI automatically may perceive neutral roadside stimuli as threatening, feel anxious in response to this perceived threat, and be ill-equipped to cope with this anxiety.3,5,17,18 According to CBT models, negative automatic thoughts play a critical role in maintaining anxiety.24 Particular cognitive distortions associated with PTSD symptomatology and combat driving experiences, such as misperceiving ambiguous stimuli as threatening because of an inability to suppress trauma-related schema and associations, may therefore maintain driving anxiety following military separation.

Research on CBT interventions suggests that cognitive restructuring, including coping self-instruction, are effective treatments to reduce anxiety.22,24 The current findings suggest that combat veterans with PTSD and TBI who experience driving anxiety endorse significantly fewer coping self-instruction thoughts than do controls in response to anxiety-provoking driving situations. In fact, prior research suggests that a majority of veterans experiencing driving-related anxiety do not seek help for their symptoms, and many of those who do prefer to reach out to friends rather than mental health professionals.2 However, due to their high levels of anxiety, these veterans likely would benefit from CBT interventions specifically targeted to coping strategies for civilian driving. These coping strategies should focus on recognizing that common roadside stimuli are not necessarily threatening in civilian environments. This type of cognitive restructuring may help veterans better manage anxiety while driving.

Limitations

The current study is limited by its small and unequal sample sizes and lack of a noncombat exposure comparison group. Additionally, while this study highlights a potential relationship between reduced cognitive coping strategies and behind-the-wheel anxiety in veterans with PTSD or TBI, causal inferences cannot be made. It is possible that individuals without coping strategies who are deployed to combat are more likely to develop PTSD or TBI. Being equipped with few coping strategies may then lead these veterans to experience greater anxiety while driving. Conversely, PTSD and TBI symptoms may prevent veterans from developing coping strategies over time.

Furthermore, the comorbid PTSD and TBI group was separated from the military for significantly longer than was the control group. Future studies using a longitudinal design could better examine the potential causal relationship between comorbid PTSD and TBI and coping and determine whether endorsement of coping self-instruction changes as a function of time since military separation.

Veterans in the current study report a variety of deployment experiences and locations. Methods of combat, type of vehicle, driving terrain, and prevalence of IEDs changed over the multiple post-9/11 military campaigns. Veterans who were deployed to Iraq in the mid-2000s were instructed to drive quickly and erratically to avoid IEDs and mortars, whereas veterans deployed in later years were taught to drive slowly and carefully to hunt for IEDs in heavily armored vehicles.3 Seventy-five percent of the veterans with PTSD or TBI in the current sample were deployed to Iraq in the early to mid-2000s, compared with 33% of the veterans without PTSD or TBI. Thus, the 2 groups in the current sample may have experienced different combat environments, which could impact how they perceived roadside stimuli. Future studies should recruit a larger and more balanced sample to better determine whether specific combat experiences impact coping strategies while driving.

Conclusion

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, the current study is the first to examine specific types of thoughts that veterans with and without PTSD or TBI experience while driving on civilian roads. Veterans with PTSD or TBI are not engaging in as many coping self-instruction thoughts behind the wheel, despite experiencing greater anxiety than that of veterans without either PTSD or TBI. Cognitive behavioral therapy interventions for anxiety include engaging in coping self-instruction during anxiety-provoking situations.22 Therefore, veterans with PTSD or TBI may benefit from learning targeted coping self-instruction thoughts that they can utilize when anxiety-provoking situations arise behind the wheel. Results suggest that clinicians should work with veterans with comorbid PTSD and TBI to develop specific coping self-instruction statements that they can utilize internally when faced with anxiety-provoking driving situations.

Acknowledgments

This study is the result of work supported by the Council on Brain Injury (grant #260472). The authors thank Dr. Rosette Biester for her guidance.