Distress Screening and Management in an Outpatient VA Cancer Clinic: A Pilot Project Involving Ambulatory Patients Across the Disease Trajectory

Mr. K. was scared about having cancer; some of his veteran colleagues have developed cancer recently, and 2 have died. He told the psychologist that he feels worthless and that this disease just makes him more of a burden on society. He has had thoughts of taking his life so that he doesn’t have to deal with cancer, but he does not have a plan. The team formulated a plan to address his anxiety and depression. Mr. K. started a serotonin reuptake inhibitor, and he met with the VA psychiatrist weekly to help develop coping strategies. The team’s psychologist worked closely with Mr. K.’s psychiatrist, and he successfully completed surgery and chemotherapy. He is now being seen in survivorship clinic, continuing care with the team and his psychologist.

Spiritual Distress

Although spiritual/religious concerns are part of DT screening, it is only a single item on the DT. Just 8% of patients (21/276) reported moderate-to-severe spiritual distress. However, there was access to a chaplain at LSCVAMC.

Case Study

Mr. H., a 63-year-old veteran with stage IV melanoma, was seen in the clinic for severe pain in his left hip and ribs (8 on a 10-point scale); he was unresponsive to escalating doses of oxycodone. During the visit, he reported that his distress level is a 10, and in addition to identifying pain as a source of distress, he indicated that he has spiritual distress. When questioned further about spiritual distress, Mr. H. reported that he deserves this pain since he caused so many others pain during his time in Vietnam. The chaplain was contacted, and the patient was seen in clinic at this visit. The chaplain gave him the opportunity to share his feelings of guilt. The importance of spiritual care when the patient is experiencing “total pain” is essential to pain management. Within 3 days, his pain score decreased to an acceptable level of 3 with no additional pharmacologic intervention.

Physical Distress

Physical problems associated with the distress scores were addressed by the surgical and medical oncologists and the APRNs (CNS patient navigator and survivorship NP). When the clinic opened, the team used the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale to assess physical and psychological symptoms.16 However, patients reported experiencing distress at having to complete 2 tools that had a great deal of overlap. The team determined that the DT could be used as the sole screening tool for all QOL domains.

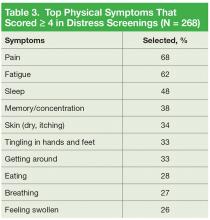

It is important to note that 92% of patients with moderate-to-severe distress reported physical symptoms as a source of distress (Table 3).

Case Study

Ms. L. is a Vietnam War veteran aged 64 years who was seen in the survivorship clinic. She was diagnosed with estrogen-receptor (ER) and progesterone-receptor (PR) breast cancer 1 year previously, had a lumpectomy followed by radiation therapy, and was on hormonal therapy. She recorded her distress score as a 6 and indicated that multiple physical symptoms were her major concern. She had difficulty with insomnia, fatigue, and hot flashes. The survivorship NP talked with Ms. L. about her symptoms and made nonpharmacologic recommendations for improving sleep, provided an exercise plan for fatigue, and initiated venlafaxine to manage the hot flashes. Ms. L. continued to be seen by the team in survivorship clinic, and during her 3-month follow-up visit, she reported improvement in sleep as the hot flashes diminished.

Multifactoral Distress

Many patients endorsed ≥ 1 component of distress. This required a team approach to intervene for the multifactorial nature of the distress.

Case Study

Mr. K. is a veteran aged 82 years who had been a farmer most of his life. He was cared for at the VA for an advancedstage squamous cell skin cancer of his scalp, which he had allowed to go untreated. The cancer has completely eroded beneath his scalp, and he wore a hat to cover the foul-smelling wound. He lived in rural Ohio with his wife of 55 years; 3 adult daughters lived in the Cleveland area. His daughters served as primary caregivers when Mr. K. came to Cleveland for daily radiation and weekly chemotherapy treatments. He had not been away from his wife since the war and misses her terribly, returning home only on weekends during the 6-week course of radiation.

His primary goal was to return home in time to harvest his farm’s produce 2 months later. He was aware that he has < 6 months to live but wanted chemotherapy and radiation to control the growth of the cancer. During this visit to the ambulatory clinic, he reported a distress score of 5 andidentified family concerns (eg, living away from his wife most of every week) and endorsed emotional concerns of fear, worry, and sadness, and reported pain, fatigue, insomnia, and constipation as physical concerns.

Mr. K. received support from the social worker, the psychologist, and the APRN for symptom management during this visit. The social worker was able to advocate for limited palliative radiation therapy treatments rather than a 6-week course; the psychologist spent 45 minutes talking with him about his fears of a painful death, worries about his wife, and sadness at not being alive for another planting season. The APRN recommended both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions for his fatigue and insomnia and initiated a pain and bowel pharmacologic regimen. The team respected Mr. K.’s wish to reconsider hospice care at the following visit after he had talked with his wife. Mr. K. died peacefully in his home with his wife and family just before the start of planting season.

Clinical Implications

Distress screening and intervention is essential for quality cancer care. While a great deal of controversy exists about the best time to screen for distress, the LSCVAMC CoE has taken on the challenge of screening and intervening in real time at every patient visit across the disease trajectory. The model of distress screening all veterans at CoE clinic visits has been rolled out to other cancer clinics at LSCVAMC.

Distress screening at each visit is not time intensive. Patients are willing to fill out the instrument while waiting for their clinic visit, and most patients find that it takes less than 5 minutes to complete. The major challenge for institutions considering screening with each visit is not the screening but access to appropriate providers able to provide timely intervention. The success of this model results, in part, because the clinic RN assesses the responses to the DT and refers to the appropriate discipline, utilizing precious resources of social work and psychology appropriately. The VA system is already committed to improving the psychosocial well-being of veterans and has established social work and psychology resources specifically for the cancer clinics.

Many patients reported to the authors that they might not have been able or willing to return to LSCVAMC to see the behavioral health specialists on another day. In addition, scheduling behavioral health appointments at another time would not allow for attending to the distress in real time. Also, from a systems standpoint, it would have been an added cost to the VA and/or the veteran for transportation for additional appointments on different days.

Finally, although the impact of the CoE project on health professional trainees has been reported elsewhere, the distress screening and intervention process were valued as being very positive for all trainees who participated in CoE clinic.17 The trainees were able to stay with the patient for the entire clinic visit, including the visits made by disciplines other than their own. For example, the family medicine residents stayed with the patient they examined to observe the distress assessments and interventions offered by the social worker and/or psychologist for the patients who scored ≥ 4 on the DT.

At the end of their rotations in the CoE, trainees reported an increased awareness of the importance of distress screening in a cancer clinic. Many were not aware of the NCCN guidelines and the ACoS CoC mandate for distress screening as a standard of cancer care. Interdisciplinary trainees rated the CoE curriculum and the conference teaching/learning sessions on distress management highly. However, observing the role of the social worker and psychologist were the most valuable to trainees, regardless of the area of practice they enter.

Conclusion

Addressing practical, psychosocial, physical, and spiritual needs will help decrease distress, support patients’ ability to tolerate treatment, and improve veterans’ QOL across the cancer-disease trajectory. Screening all patients at an outpatient cancer clinic at LSCVAMC is feasible and does not seem to be a burden for patients or providers. This pilot project has become standard of care across the LSCVAMC cancer clinics, demonstrating its sustainability.

Screening with the DT provides information about the intensity of the distress and the components contributing to the distress. The most important aspect of the screening is assessing the components of the distress and providing real-time intervention from the appropriate discipline. It is critical that the oncology team refer to the appropriate discipline based on the source of the distress rather than on only the intensity. Findings from this project indicate that physical symptoms are frequently the source of distress and may not require behavioral health intervention. However, for patients with psychosocial needs, rapid access to behavioral health care services is critical for quality veteran-centered cancer care.

Since 2015, all VA cancer centers are required to have implemented distress screening. According to the CoC, at least 1 screening must be done on every patient.10 Many institutions have begun to screen at diagnosis, but it is well known that there are many points along the cancer trajectory when patients may experience an increase in distress. Simple screening with the DT at every cancer clinic visit helps identify the veterans’ needs at any point along the disease spectrum.

At LSCVAMC, the CoE was designed as an interdisciplinary cancer clinic. With the conclusion of funding in FY 2015, the clinic has continued to function. The rollout into other clinics has continued with movement toward use of formal consult requests and continual, real-time evaluation of the process. Work on accurate, timely identification of new cancer patients and identifying pivotal cancer visits is underway. The LSCVAMC is committed to improving care and access to its veterans with cancer to ensure appropriate and adequate services across the cancer trajectory.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.