Bolus Insulin Prescribing Recommendations for Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

Method 2: Basal-Bolus

When basal plus is insufficient to get the HbA1c and BG readings to goal, taking bolus insulin for all main meals containing carbohydrates must be considered. This is often called basal-bolus, multiple daily injections, or intensive insulin therapy.

In order to understand the concept of basal-bolus, HCPs should consider normal physiology. The pancreas releases a constant amount of insulin, aka background insulin, to cover glucose produced by the liver to the cells between meals. In addition, a burst of insulin, aka bolus insulin, to meet the blood glucose elevation from food to maintain homeostasis. In patients with T2DM, the relative amount produced by the pancreas is insufficient to meet the demand due to pancreatic exhaustion or insulin resistance. This necessitates the need to replace background and bolus insulin.7

The ideal final total bolus insulin amount (the sum of all meal bolus doses) should be about half the basal dosing. Calculation of starting bolus dosing can be done as in the basal plus regimen, either 4 to 6 units per meal or 0.1 U/kg/d.10 Alternatively, if the patient is on 60 units of long-acting analog and BGs are well above goal range, the prescriber could consider about 20 units of bolus dose (60 U divided by 3 meals) if the patient eats 3 routine meals a day with at least 30 g of carbohydrates, and physical activity levels are fairly consistent. If the patient eats the most carbohydrates at lunchtime, consider more bolus at lunch (ie, 18 U of bolus for breakfast and dinner and 24 U of bolus for lunch coverage). Patients need to separate the time between the bolus doses, usually a minimum of 4 hours apart, to avoid insulin stacking, which is a common reason for hypoglycemia. Insulin stacking occurs when additional quick or rapid insulin is injected when the previous insulin is still in the body or when there is insulin on board.8,11 Typically, bolus analogs stay in the body for about 4 to 6 hours, thus necessitating separation of the doses at least 4 hours apart. Patients sometimes inject more bolus insulin after high postprandial readings, which can result in insulin stacking. In some cases, the patient may misunderstand and take mealtime insulin at a scheduled time instead of at the time of the meal.

Injecting bolus insulin for every snack must be avoided to prevent a vicious cycle: Postprandial hyperglycemia –> extra bolus insulin, resulting in insulin stacking –> hypoglycemia –> overtreatment with food –> hyperglycemia –> extra bolus insulin, resulting in insulin stacking –> and so on. Whenever there are readings in the hypoglycemic and hyperglycemic range, address hypoglycemia first because hyperglycemia often is due to overtreatment of hypoglycemia.

Method 3: Premix or Split-Mix (Patient-Mix) Insulin

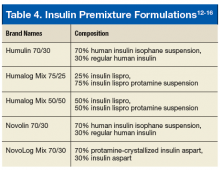

Postprandial BG excursions can be minimized by changing basal insulin to premix or split-mix (patient-mix) insulin that has a mixture of mealtime and intermediate action insulin (Table 4).12-16 The use of premixed insulin is a viable option due to its ease of use and for those who have restrictions based on the complexity of the basal-bolus regimen.7 If a patient has routine meals and prefers not to carry around insulin for lunch, the schedule of premix insulin taken at breakfast and dinner is ideal.

Some caveats for safe prescribing should be understood. A recent summary of premixed insulin regimens noted that they seem to have a similar efficacy and safety profile compared with regimens that include basal insulin with or without mealtime insulin; however, cost and patient adherence are improved.17 It is important to monitor insulin-naïve patients for hypoglycemia and reduced efficacy when used twice daily compared with basal plus 3-times daily prandial insulin in patients needing insulin intensification.17

A randomized trial noted that hypoglycemia rates were twice as high with premixed insulin compared with basal-bolus insulin.18 This study also noted that the premixed insulin group experienced the highest dropout rate, partly due to hypoglycemia. A regimen of basal insulin with the option to add a single prandial insulin injection at the main meal was as effective in reducing HbA1c with less hypoglycemia. The premixed insulin is convenient but does not allow a separate correction of either mealtime or intermediate-acting insulin doses. If the premixed dose needs to be adjusted due to fasting hyperglycemia > 180 mg/dL(10.0 mmol/L), the TDD can be increased by 10%.2

In contrast, a split-mix (patient-mix) insulin regimen allows for the ability to vary the amount/ratio of combinations and adjustment of bolus and intermediate insulin doses. The disadvantages of split-mix insulin include the inconvenience of manually mixing of insulin and the potential for dosing errors. The patient needs to be taught additional steps on how to mix both insulins. Ensure the correct mixing order to maintain insulin potency; regular first, then neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH). An HCP should remember the RN acronym if the patient is combining regular insulin and NPH. If there is doubt about the patient’s insulin injection technique, HCPs should ask the patient to demonstrate how to correctly pull up a dose of normal saline and inject it during a clinic visit. The only basal insulin that can be physically mixed with quick or rapid insulin is NPH. It should never be mixed with long-acting analogs. The patient should not even use the same syringe to draw up bolus analog insulin and inject it and then use the same syringe to draw up long-acting analog insulin.

One caveat to a fixed regimen (same amount of insulin dose) is that providers often expect that the patient will eat a consistent amount of carbohydrates at each meal and premeal glucose readings are fairly stable. Oftentimes, this is not true. If a patient took a bolus dose of 8 units of rapid-acting insulin and ate a 6 oz steak, 3 oz baked potato, steamed broccoli at a dinner; and no bread, the after dinner BG might register 145 mg/dL (8.1 mmol/L). Then, the next day for dinner, if he or she took the same amount of 8 units of rapid-acting insulin and ate 1 cup of spaghetti, ½ cup of spaghetti meat sauce, and 2 slices of garlic bread, the after dinner reading might be 322 mg/dL (17.9 mmol/L). The patient’s BG was higher on the second day because of the higher carbohydrate content of the meal. If the rapid-acting insulin was increased to 12 units of bolus based on the high carbohydrate meal and the patient ate a lower carbohydrate meal, hypoglycemia could ensue. Thus, it is important to work with the patient regarding the consumption of a consistent amount of carbohydrates and refer to a registered dietitian for carbohydrate consistency.

For the flexible regimen, the prescriber may consider using an insulin to carbohydrate (IC) ratio and sensitivity factor (SF), also called sliding scale or correction factor. The IC ratio represents how much insulin is needed to cover consumed carbohydrates. For instance, if the patient uses IC ratio of 1:15, 1 unit of bolus insulin will cover 15 g of carbohydrates. If the patient eats a meal with 60 g of carbohydrates and is using IC ratio of 1:15, the patient will inject 4 units of bolus insulin. Sensitivity factor represents how much BG will be lowered in mg/dL by taking 1 unit of bolus insulin. For example, if the patient uses SF of 1:50, 1 unit of bolus insulin will lower BG by 50 mg/dL (2.8 mmol/L). When the desired (target) BG reading is 100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L) and the patient’s current BG is 200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L), the patient will divide 100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L) by 50 (derived from SF of 1:50). The net result is 2 units of bolus insulin are needed to lower BG by 100 mg/dL (5.6 mmol/L). If the premeal BG is 200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L) and 60 g of carbohydrates are eaten, then the patient will need a total of 6 units (4 U for carbohydrate and 2 U for high BG) bolus before the meal. For additional information, readers are encouraged to read the articles by Petznick and by Joslin Diabetes Center for IC and SF.19,20