Sarcopenia and the New ICD-10-CM Code: Screening, Staging, and Diagnosis Considerations

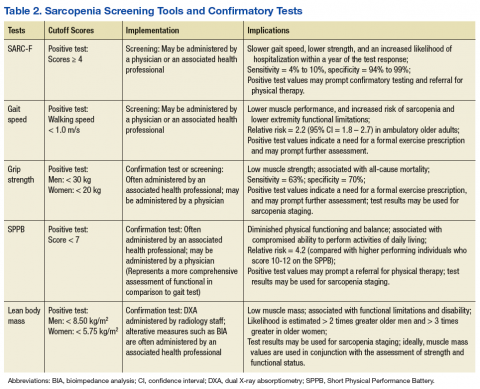

Gait speed (in those who are ambulatory) and grip-strength values could be entered into the EMR evaluation note by the primary care provider (PCP). Elements of the VA EMR, such as the ability to review the diagnosis of sarcopenia on the Problem List or the nominal enhancement of providing LBM estimates within the Cumulative Vitals and Measurements Report would support the management of sarcopenia. See Table 2 for cutoff values for frequently used sarcopenia screening and staging tests.

The pitfalls of excessive or inappropriate screening are well documented. The efforts to screen for prostate cancer have highlighted instances when inappropriate followup tests and treatment fail to alter mortality rates and ultimately yield more harm than good.30 However, there are several points of departure concerning the screening for sarcopenia vs screening for prostate cancer. The screening assessments for sarcopenia are low-cost procedures that are associated with a low patient burden. These procedures may include questionnaires, functional testing, or the assessment of muscle performance. Additionally, there is a low propensity for adverse effects stemming from treatment due to disease misclassification given the common nonpharmacologic approaches used to manage sarcopenia.31 Nonetheless, the best screening examination—even one that has low patient burden and cost—may prove to be a poor use of medical resources if the process is not linked to a viable intervention.

Screening people aged ≥ 65 years may strike a balance between controlling health care expenditures and identifying people with the initial signs of sarcopenia early enough to begin monitoring key outcomes and providing a formalized exercise prescription. Presuming an annual age-related decline in LBM of 1.5%, and considering the standard error measurement of the most frequently used methods of strength and LBM assessment, recurrent screening could occur every 2 years.21,32

Earlier screening may be considered for patient populations with a higher pretest probability. These groups include those with conditions associated with accelerated muscle loss, such as chronic kidney disease, peripheral artery disease, and diabetes mellitus (DM).32 Although accelerated muscle loss characterized by an inflammatory motif (eg, cancer-related cachexia) may share some features of the sarcopenia screening and assessment approach, important differences exist regarding the etiology, medical evaluation, and ICD-10-CM code designation.

Staging and Classification

Staging criteria are generally used to denote the severity of a given disease or syndrome, whereas classification criteria are used to define homogenous patient groups based on specific pathologic or clinical features of a disorder. Although classification schemes may incorporate an element of severity, they are primarily used to characterize fairly distinct phenotypic forms of disease or specific clinical presentation patterns associated with a well-defined syndrome. Although not universally adopted, the European consensus group sarcopenia staging criteria are increasingly used to provide a staging algorithm presumably driven by the severity of the condition.19

The assessment of functional performance for use in sarcopenia staging often involves measuring habitual gait speed or completing the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB).23 The SPPB involves a variety of performance-based activities for balance, gait, strength, and endurance. This test has predictive validity for the onset of disability and adverse health events, and it has been extensively used in research and clinical settings.33 Additional tests used to characterize function during the staging or diagnostic process include the timed get up and go test (TGUG) and the timed sit to stand test.34,35 The TGUG provides an estimate of dynamic balance, and the sit to stand test has been used as very basic proxy measure of muscular power.36 The sit to stand test and habitual gait speed are items included in the SPPB.33

Accepted methods to obtain the traditional index measure of sarcopenia—based on estimates of LBM—include bioimpedance analysis (BIA) and dual X-ray absorptiometry (DXA). The BIA uses the electrical impedance of body tissues and its 2 components, resistance and reactance, to derive its body composition estimates.37 Segmental BIA allows for isolated measurements of the limbs, which may be calibrated to DXA appendicular lean body mass (ALM) or magnetic resonance imaging-based estimates of LBM. This instrument is relatively safe for use, inexpensive for medical facilities, and useful for longitudinal studies, but it can be confounded by issues, such as varying levels of hydration, which may affect measurement validity in some instances.

Despite the precision of DXA for estimating densities for whole body composition analysis, the equipment is not very portable and involves low levels of radiation exposure, which limits its utility in some clinical settings. While each body composition assessment method has its advantages and disadvantages, DXA is regarded as an acceptable form of measurement for hospital settings, and BIA is frequently used in outpatient clinics and community settings. Other methods used to estimate LBM with greater accuracy, such as peripheral quantitative computed tomography, doubly labeled water, and whole body gamma ray counting, are not viable for clinical use. Other accessible methods such as anthropometric measures and skinfold measures have not been embraced by sarcopenia classification consensus groups.23,37

Alternative methods of estimating LBM, such as diagnostic ultrasound and multifrequency electrical impedance myography, are featured outcomes in ongoing clinical trials that involve veteran participants. These modalities may soon provide a clinically viable approach to assessing muscle quality via estimates of muscle tissue composition.37,38 Similar to the management of other geriatric syndromes, interprofessional collaboration provides an optimal approach to the assessment of sarcopenia. Physicians and other health care providers may draw on the standardized assessment of strength and function (via the SPPB and hand-grip dynamometry) by physical therapists (PTs), questionnaires administered by nursing staff (the SARC-F), or body composition estimates from other health professionals (ranging from BIA to DXA) to aid the diagnostic process and facilitate appropriate case management (Table 2).

Competing staging and classification definitions have been cited as a primary factor behind the CDC’s delayed recognition of the sarcopenia diagnosis, which in turn posed a barrier to formal clinical recognition by geriatricians.24 However, this reaction to the evolving sarcopenia staging criteria also may reveal the larger misapplication of the staging process to the diagnostic process. The application of classification and staging criteria results in a homogenous group of patients, whereas the application of diagnostic criteria results in a heterogeneous group of patients to account for variations in clinical presentation associated with a given disorder. Classification criteria may be equivalent to objective measures that are used in the diagnostic process when a given disease is characterized by a well-established biomarker.39

However, this is not the case for most geriatric syndromes and other disorders marked by varied clinical presentation patterns. On considering the commonly used sarcopenia staging criteria of LBM ≤ 8.50 kg/m2 or grip strength < 30 kg in men and LBM ≤ 5.75 kg/m2 or grip strength < 20 kg in women, it is easy to understand that such general cutoff values are far from diagnostic.40,41 Moreover, stringent cutoff values associated with classification and staging may not adequately capture those with an atypical presentation of the syndrome (eg, someone who exhibits age-related muscle weakness but has retained adequate LBM). Such criteria often prove to have high specificity and low sensitivity, which may yield a false negative rate that is appropriate for clinical research eligibility and group assignment but inadequate for clinical care.

Screening, staging, and classification criteria with high specificity may indeed be desirable for confirmatory imaging tests associated with radiation exposure concerns or for managing risk in experimental clinical trials involving pharmacologic treatment. For example, a SARC-F score ≥ 4 may prompt the formal assessment of LBM via a DXA examination.4 In contrast, those with a SARC-F score ≤ 3 with low gait speed or grip strength may benefit from consultation regarding regular physical activity and nutrition recommendations. Given the challenges of establishing sarcopenia classification criteria that perform consistently across populations and geographic regions, classification and staging criteria may be best viewed as clinical reasoning tools that supplement, but not supplant, the diagnostic process.7,42

Diagnosis

Geriatric syndromes do not lend themselves to a simple diagnostic process. Syndromes such as frailty and sarcopenia are multifactorial and lack a single distinguishing clinical feature or biomarker. The oft-cited refrain that sarcopenia is an underdiagnosed condition is partially explained by the recent ICD-10-CM code and varied classification and diagnostic criteria.5 This circumstance highlights the need to distinctly contrast the diagnostic process with the screening and staging classifications.

The diagnostic process involves the interpretation of the patient history, signs, and symptoms within the context of individual factors, local or regional disease prevalence, and the results of the best available and most appropriate laboratory tests. After all, a patient that presents with low LBM and a gradual loss of strength without a precipitating event would necessitate further workup to rule out many clinical possibilities under the aegis of a differential diagnosis. Clinical features, such as the magnitude of weakness and pattern of strength loss or muscle atrophy along with the determination of neurologic or autoimmune involvement, are among the key elements of the differential examination for a case involving the observation of frank muscle weakness. Older adults with low muscle strength may have additional risk factors for sarcopenia such as obesity, pain, poor nutrition, previous bone fracture, and a sedentary lifestyle. However, disease etiology with lower probabilities, such as myogenic or neurogenic conditions associated with advancing age, also may be under consideration during the clinical assessment.6

In many instances, the cutoff scores associated with the sarcopenia staging criteria may help to guide the diagnostic process and aid clinical decision making. Since individuals with a positive screening result based on the SARC-F questionnaire (score ≥ 4) have a high likelihood of meeting the staging criteria for severe sarcopenia, a PCP may opt to obtain a confirmatory estimate of LBM both to support the clinical assessment and to monitor change over the course of rehabilitation. Whereas people who present with a decline in strength (ie, grip strength < 30 kg for a male) without an observable loss of function or a positive SARC-F score may benefit from consultation from the physician, NP, or rehabilitation health professional regarding modifiable risk factors associated with sarcopenia.

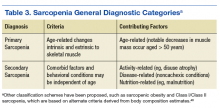

Incorporating less frequently used sarcopenia classification schemes such as identifying those with sarcopenic obesity or secondary sarcopenia due to mitigating factors such as chronic kidney disease or DM (Table 3) may engender a more comprehensive approach to intervention that targets the primary disease while also addressing important secondary sequelae. Nevertheless, staging or classification criteria cannot be deemed equivalent to diagnostic criteria for sarcopenia due to the challenges posed by syndromes that have a heterogeneous clinical presentation.

The refinement of the staging and classification criteria along with the advances in imaging technology and mechanistic research are not unique to sarcopenia. Practitioners involved in the care of people with rheumatologic conditions or osteoporosis also have contended with continued refinements to their classification criteria and approach to risk stratification.39,43,44 Primary care providers will now have the option to use a new ICD-10-CM code (M62.84) for sarcopenia, which will allow them to properly document the clinical distinctions between people with impaired strength or function largely due to age-related muscle changes and those who have impaired muscle function due to cachexia, inflammatory myopathies, or forms of neuromuscular disease.