Nonpathologic Postdeployment Transition Symptoms in Combat National Guard Members and Reservists

Health care providers are in the unique position to promote a healthy postdeployment transition by assisting veterans to recognize nonpathologic transition symptoms, select appropriate coping strategies, and seek further assistance for more complex problems.

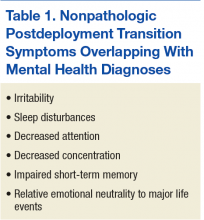

Relationship of Symptoms to Mental Health Diagnoses

Postdeployment transition symptoms do not automatically indicate the presence of an underlying mental health diagnosis. However, persistent and/or severe symptoms of postdeployment transition can overlap with or contribute to the development of mental health concerns (Table 1).14 The effects of the emotional disconnect also can exacerbate underlying mental health diagnoses.

While postdeployment emotional numbness to major life events, irritability, sleep disturbances, and impaired concentration can be associated with acute stress disorder (ASD) or PTSD, there is a constellation of other symptoms that must be present to diagnose these psychiatric conditions.16 Diagnostic criteria include persistent intrusive symptoms associated with the trauma, persistent avoidance of triggers/reminders associated with the trauma, significant changes in physiologic and cognitive arousal states, and negative changes in mood or cognition related to the trauma.16 The symptoms must cause significant impairment in some aspect of functioning on an individual, social, or occupational level. Acute stress disorder occurs when the symptoms last 30 days or less, whereas PTSD is diagnosed if the symptoms persist longer than a month.

Impaired emotional regulation, sleep disturbances, and decreased concentration also can be associated with depression or anxiety but are insufficient in themselves to make the diagnosis of those disorders.16 At least a 2-week history of depressed mood or inability to experience interest or pleasure in activities must be present as one of the criteria for depression as well as 4 or more other symptoms affecting sleep, appetite, energy, movement, self-esteem, or suicidal thoughts. Anxiety disorders have varying specific diagnostic criteria, but recurrent excessive worrying is a hallmark. Just like ASD or PTSD, the diagnostic symptoms of either depression or anxiety disorders must be causing significant impairment in functioning on an individual, social, or occupational level.

Irritability, sleep disturbances, agitation, memory impairment, and difficulty with concentration and attention can mimic the symptoms associated with mild-to-moderate traumatic brain injury (TBI).17,18 However, symptom onset must have a temporal relationship with a TBI. The presence of other TBI symptoms not associated with normal postdeployment transition usually can be used to differentiate between the diagnoses. Those TBI symptoms include recurrent headaches, poor balance, dizziness, tinnitus, and/or light sensitivity. In the majority of mild TBI cases, the symptoms resolve spontaneously within 3 months of TBI symptom manifestation.16,19 For those with persistent postconcussive syndrome, symptoms usually stabilize or improve over time.18,19 If symptoms worsen, there is often a confounding diagnosis such as PTSD or depression.17,20,21

Some returning combat veterans mistakenly believe postdeployment emotional transition symptoms are always a sign of a mental health disorder. Because there is a significant stigma associated with mental health disorders as well as potential repercussions on their service record if they use mental health resources, many reservists and National Guard members avoid accessing health care services if they are experiencing postdeployment adjustment issues, especially if those symptoms are related to emotional transitions.22-24 Unfortunately, such avoidance carries the risk that stress-inducing symptoms will persist and potentiate adjustment problems.

Course of Symptoms

The range for the postdeployment adjustment period generally falls within 3 to 12 months but can extend longer, depending on individual factors.10,11,25 Factors include presence of significant physical injury or illness, co-occurrence of mental health issues, underlying communication styles, and efficacy of coping strategies chosen. Although there is no clear-cut time frame for transition, ideally transition is complete when the returning veteran successfully enters his or her civilian lifestyle roles and feels a sense of purpose and belonging in society.

Postdeployment transition symptoms occur on a continuum in terms of duration and intensity for reservists and National Guard members. It is difficult to predict how specific transition symptoms will affect a particular veteran. The degree to which those symptoms will complicate reintegration depends on the individual veteran’s ability to adapt within the psychosocial context in which the symptoms occur. For example, minor irritation may be short-lived if a veteran can employ techniques to diffuse that feeling. Alternatively, minor irritation also suddenly may explode into a powerful wave of anger if the veteran has significant underlying emotional tension. Similarly, impaired short-term memory may be limited to forgetting a few appointments or may be so common that the veteran is at risk of losing track of his or her day. The level of memory impairment depends on emotional functioning, co-occurring stressors, and use of adaptive strategies.

In general, as these veterans successfully take on civilian routines, postdeployment transition symptoms will improve. Although such symptom improvement may be a passive process for some veterans, others will need to actively employ strategies to help change the military combat mind-set. The goal is to initiate useful interventions early in transition before symptoms become problematic.14

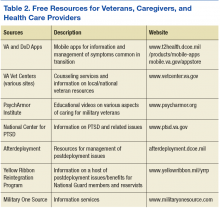

There are numerous self-help techniques and mobile apps that can be applied to a wide number of symptoms. Viable strategies include exercise, yoga, meditation, mindfulness training, and cognitive reframing. Reaching out for early assistance from various military assistance organizations that are well versed in dealing with postdeployment transition challenges often is helpful for reducing stress and navigating postdeployment obstacles (Table 2).

Symptom Strain and Exacerbation

Whenever stumbling blocks are encountered during the postdeployment period, any transition symptom can persist and/or worsen.10,11,14 Emotional disconnect and other transition symptoms can be exacerbated by physical, psychological, and social stressors common in the postdeployment period. Insomnia, poor quality sleep, or other sleep impairments that frequently occur as part of postdeployment transition can negatively impact the veteran’s ability to psychologically cope with daytime stressors. Poor concentration and short-term memory impairment noted by many reservists and National Guard members in the postdeployment phase can cause increased difficulty in attention to the moment and complicate completion of routine tasks. These difficulties can compound frustration and irritation to minor events and make it hard to emotionally connect with more serious issues.

Concentration and attention to mundane activities may be further reduced if the veteran feels no connection to the civilian world and/or experiences the surreal sensation that he or she should be attending to more serious life and death matters, such as those experienced in the combat theater. Ongoing psychological adjustment to physical injuries sustained during deployment can limit emotional flexibility when adapting to either minor or major stressors. Insufficient financial resources, work issues, or school problems can potentiate irritation, anger, and sadness and create an overwhelming emotional overload, leading to helplessness and hopelessness.

Perceived irregularities in emotional connection to the civilian world can significantly strain interpersonal relationships and be powerful impediments to successful reintegration.9,11,14 Failure to express emotions to major life events in the civilian world can result in combat veterans being viewed as not empathetic to others’ feelings. Overreaction to trivial events during postdeployment can lead to the veteran being labeled as unreasonable, controlling, and/or unpredictable. Persistent emotional disconnect with civilians engenders a growing sense of emotional isolation from family and friends when there is either incorrect interpretation of emotional transitions or failure to adapt healthy coping strategies. This isolation further enlarges the emotional chasm and may greatly diminish the veteran’s ability to seek assistance and appropriately address stressors in the civilian world.

Transition and the Family

Emotional disconnection may be more acutely felt within the immediate family unit.26 Redistribution of family unit responsibilities during deployment may mean that roles the veteran played during predeployment now may be handled by a partner. On the veteran’s return to the civilian world, such circumstances require active renegotiation of duties. Interactions with loved ones, especially children, may be colored by the family members’ individual perspectives on deployment as well as by the veteran’s transition symptoms. When there is disagreement about role responsibilities and/or underlying family resentment about deployment, conditions are ripe for significant discord between the veteran and family members, vital loss of partner intimacy, and notable loss of psychological safety to express feelings within the family unit. If there are concerns about infidelity by the veteran or significant other during the period of deployment, postdeployment tensions can further escalate. If unaddressed in the presence of emotional disconnect, any of these situations can raise the risk of domestic violence and destruction of relationships.

Without adequate knowledge of common postdeployment transitions and coping strategies, the postdeployment transition period is often bewildering to returning veterans and their families. They are taken aback by postdeployment behaviors that do not conform to the veteran’s predeployment personality or mannerisms. Families may feel they have “lost” the veteran and view the emotionally distant postdeployment veteran as a stranger. Veterans mistakenly may view the postdeployment emotional disconnect as evidence that they were permanently altered by deployment and no longer can assimilate into the civilian world. Unless veterans and families develop an awareness of the postdeployment transition symptoms and healthy coping strategies, these perspectives can contribute to a veteran’s persistent feelings of alienation, significant sense of personal failure, and loss of vital social supports.