Improving Veteran Access to Treatment for Hepatitis C Virus Infection

Phase 2: Increase Recruitment

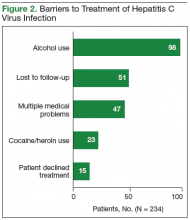

The records of 534 patients with advanced liver disease (F3-F4 fibrosis on the Fibrosis-4 Index for Liver Fibrosis) and HCV infection were identified in the CCR database for the period August 2015 to December 2015 (Figure 1).8 Patients were excluded if they were deceased, were receiving palliative care (n = 45), or if they had transferred their care to another VA facility (n = 69). Of the 420 patients in the study reviewed, 234 (56%) had not previously been referred to an HCV clinic or been started on treatment because of a variety of social issues, including active substance use (Figure 2).

Many of the patients were difficult to engage because the clinic could not effectively assist them in achieving sobriety and lacked support personnel who could address their complex social issues. Given the availability of all-oral HCV treatments, the VA Public Health Department issued guidance allowing all HCV-infected patients to receive DAA treatment regardless of ongoing drug or alcohol use disorders.9 Substance use was not to be considered a contraindication to therapy. It was suggested that health care providers determine these patients’ treatment eligibility on a case-by-case basis. An official VA memorandum supporting this initiative was released in September 2016.10

Interventions

In an effort to engage all HCV-infected patients, the CCR review was expanded to include patients without advanced liver disease. All patients were contacted by mail. Any patient registered for secure messaging through MyHealtheVet also received a secure message. Patients were informed about the newly approved DAA therapies and were connected directly with specialized HCV clinic schedulers at RLRVAMC. Patients who responded were scheduled for a group education class facilitated by 2 members of the HCV treatment team.

Unlike patients in the group treatment clinic, patients in the education class had not completed the necessary workup for treatment initiation. In the class, patients received education on new HCV treatments and were linked to social work care if needed to streamline the referral process. All baseline laboratory test results also were obtained.

Another intervention implemented to recruit patients in this difficult-to-treat population was the addition of a social worker to the treatment team. Beginning in late June 2016, high-risk patients were referred to the social worker by HCV providers or pharmacists. For each referred patient, the social worker performed a psychosocial assessment to identify potential barriers to successful treatment and then connected the patient with either VA or community resources for support.

The social worker linked patients to mental health or substance use-related services, empowered them to access transportation resources for clinic appointments, orchestrated assistance with medication adherence from a home health nurse, and reached out to patients in person or by telephone to address specific needs that might limit their ability to attend appointments. The social worker also provided harm reduction planning and goal setting support to help patients with substance use disorders achieve sobriety or reduce substance use while on HCV treatment. All efforts were made to ensure that patients adhered to their clinic visits and medication use. In addition, during social work assessment, factors such as housing concerns, travel barriers, and loss and grief were identified and promptly addressed.

Results

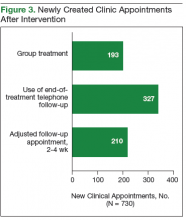

After the phase 1 intervention, 730 additional appointments were added in FY 2016 (Figure 3). As a result, 409 patients with HCV infection were started on treatment in FY 2016 compared with 192 in FY 2015. More important, the rapid increase in capacity and treatment initiation did not sacrifice the quality of care provided. Ninety-eight percent of patients who started treatment in FY 2016 successfully completed their treatment course. The overall SVR12 rate was 96% for all genotype 1 patients treated with ledipasvir/sofosbuvir, ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir plus dasabuvir, or elbasvir/grazoprevir with or without ribavirin. In addition, the SVR12 rate was 82% for genotype 2 patients (almost all cirrhotic) treated with sofosbuvir plus ribavirin and 93% for genotype 3 patients treated with daclatasvir, sofosbuvir, and ribavirin.

Phase 2: Increase Recruitment

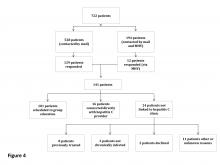

The expanded CCR review identified 234 patients with advanced liver disease and 546 patients without advanced disease. As this was a rolling review, 58 patients were linked to care before being contacted. Of the 722 patients in the cohort, 528 were contacted by mail and 194 both by mail and by MyHealtheVet messaging. One hundred forty-one patients responded: 129 by mail and 12 by MyHealtheVet messaging (eFigure 1).

Of the 101 patients scheduled for group education, 43 attended education in FY 2016 (eFigure 2).