Veterans as Caregivers:Those Who Continue to Serve

Results

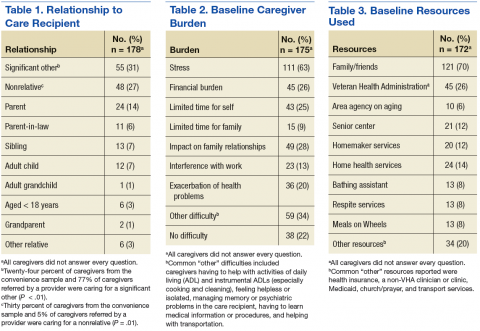

For the study, 433 PCC veterans were interviewed, and 157 (36%) self-identified as a caregiver. An additional 22 referrals were included for a total of 179 caregivers. Caregiver and care recipient characteristics, caregiver burden, and resource utilization were calculated for all 179 caregivers; however, all caregivers did not answer every question. Ninety-eight percent (176) of caregivers were men; 64% (109/170) were from Salt Lake County, and 5% were from outside Utah (8). Twelve percent (21) of the 179 caregivers were providing care for > 1 person. Of 177 caregivers, 3% (5) were caring for both a veteran and a nonveteran, 69% (122) were caring for a nonveteran only, and 28% (49) were caring for another veteran only (Table 1).

The most common burden reported by caregivers was stress (63%); 70% endorsed family/friends as a resource (Table 2). Just 6% (10) of caregivers used the AAA, whereas 26% (45) received VHA support. Of the 54 veterans who were caring for a veteran, 40 reported using the VHA as a resource. Five people caring for nonveterans reported using the VHA as a resource; however, data about which resources those caregivers were accessing were not collected (Table 3).

AAA Referral and Randomization

Sixty-five percent of caregivers accepted AAA referrals. Of 109 Salt Lake County caregivers, 70% accepted referral to the AAA. There was no statistically significant difference in referral acceptance rates when comparing Salt Lake County residents with nonresidents (P = .09).The authors were unable to obtain the phone number for 1 caregiver who had accepted a referral, and 1 caregiver who accepted referral did not want a follow-up. This left 111 caregivers available for follow-up, 75 in Salt Lake County. Fifty Salt Lake County veterans were randomly assigned to the VIR group and 25 to the PIR group. The 36 caregivers who accepted referrals outside Salt Lake County also were placed in the VIR group, for a total of 86 caregivers.

Follow-up

Ninety-eight percent of caregivers were reached for follow-up. Both people lost to follow-up were in Salt Lake County (1 in each group).

In Salt Lake County, 12% (6) of the VIR group and 64% (16) of the PIR group had connected with the AAA (P < .01). Although 64% of those in the PIR group reported having been called by the AAA, the AAA representative reported all 25 had been called. The AAA records showed 9 of those called were reached by voice mail, 6 were provided information about caregiving resources, 2 formally joined the support program, 5 declined help, 1 was no longer caregiving, 1 was too busy to talk, and 1 was the wrong phone number (and was lost to follow-up as well).

Outside of Salt Lake County 19% (7) reported calling the local AAA. There was no difference in referral completion between the Salt Lake County/non-Salt Lake County VIR groups (P = .4).

Fifteen percent of all VIR caregivers reported calling the AAA. There were no statistical differences between Salt Lake County VIR and non-Salt Lake County VIR for reasons why the veteran had not called the AAA (Table 4).

Of 28 people who connected with the AAA, 16 (57%) said they had received access to a needed resource as a result of the phone call. Seven caregivers (25%) said they had not been referred to other resources as a result of the call. The VIR group was more likely to be referred to other resources after contacting the AAA than was the PIR group, although this difference did not reach significance (69% vs 47%, P = .28).

Discussion

More than one-third (36%) of veterans seen in the VASLCHCS PCC are caregivers. This prevalence is higher than that reported for the general U.S. population and higher than that reported in other veteran groups.5,17,18 Most caregivers in this project were caring for nonveterans and only had access to VHA psychosocial caregiver support programs because VHA functional caregiver support (eg, respite, homemaker services) is not available to veterans who care for nonveterans. A majority (78%) of caregiving veterans reported some caregiver burden. Despite the burden, most are not using community resources. However when offered, more than half the caregivers were interested in an AAA referral.

Although the VHA does not provide functional caregiver support resources to veterans caring for nonveterans, there are other agencies that can assist veterans: AAAs for care recipients aged ≥ 60 years and the ADRCs for younger veterans. Through AAAs, caregivers can access a variety of support services, including transportation, adult day care, caregiver support, and health promotion programs. Partnership between agencies such as the VHA and the AAAs could benefit caregiving veterans. This QI project suggests ways to strengthen interagency cooperation.

This study also suggests that a provider or clinic-initiated referral is more likely to connect veterans with information and resources than the current practice of recommending that the veteran initiate the referral. Once in contact with the AAA, most caregivers were referred to needed resources. The next step will be to establish an efficient way for clinic staff to identify caregiving veterans and make referrals to community programs. Referrals could be made by any member of the patient aligned care team (PACT) to further standardize and streamline the process.

Thirty-one percent of veterans in this project were eligible for the VHA caregiver support program because they cared for a veteran. However, 25% of these caregiving veterans were not accessing this resource. Increasing awareness of the VHA caregiver support program among veterans caring for other veterans would improve caregiver support to both caregiving and care recipient veterans.