A cognitive-behavioral strategy for preventing suicide

Consider a 3-phase course of CBT to put distance between a patient and repeat suicide attempts, in outpatient and inpatient settings

Practitioners must ensure that the safety plan contains contact information that the patient can use to reach the practitioner, the clinic, the on-call provider (if available), the local 24-hour emergency department, and the 24/7 National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (800-273-TALK [8255]). Discussion of how to limit access to lethal means also is important.

Because safety planning is a collaborative process, it is imperative that practitioners check on the patient’s willingness to follow the safety plan and help him overcome perceived obstacles in implementation. Copies of the plan can be kept at different locations and shared with family members, friends, or both with the patient’s permission.

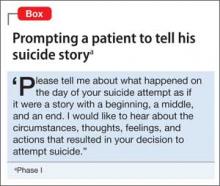

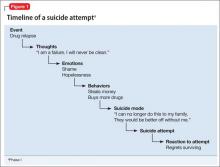

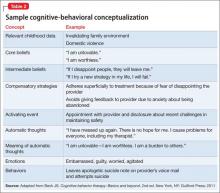

Develop a cognitive-behavioral conceptualization. The cognitive-behavioral conceptualization is an individualized map of a patient’s automatic thoughts (eg, “I am going to get fired today”), conditional assumptions (“If I get fired, then my life is over”), and core beliefs (“I am an utter failure”) that are activated before, during, and after suicidal self-directed violence. To develop that conceptualization, the patient is asked to tell a story about his (her) most recent suicidal crisis (the Box, offers a sample script) and to describe reactions to having survived a suicide attempt. (Note: Patients who report regret after an attempt are at greatest risk for dying by suicide.10)

This activity gives the patient an opportunity to disclose details surrounding his suicidal thoughts and actions, and might allow for a cathartic experience through storytelling. As practitioners listen to the suicide narrative, they collect data on the patient’s early childhood experiences (typically, suicide-activating events), associated automatic thoughts and images, emotional responses, and subsequent behaviors.

Based on this information, a cognitive-behavioral case conceptualization diagram (Figure 1, and Table 2) is generated collaboratively with the patienta and used to personalize treatment planning.

a Judith Beck offers sample case conceptualization diagrams in Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond, 2nd ed. New York, New York: Guilford Press; 2011.

Phase II: Build skills

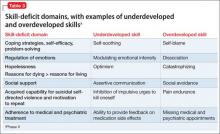

Build skills to prevent episodes of suicidal self-directed violence. Information obtained from the conceptualization is used to generate an individualized cognitive-behavioral plan of intervention. The overall goal is to determine skill-based problem areas that are associated with the most recent episode of suicidal self-directed violence.

Practitioner and patient collaboratively identify skills that are underdeveloped and ones that are overdeveloped so that they can be addressed systematically. In general, based on our clinical experience with suicidal patients, we recommend focusing on skills captured within ≥1 of the deficit domains in Table 3. Explanation of the various cognitive-behavioral strategies used in this phase of treatment is beyond the scope of this article, but 2 activities that highlight the clinical work conducted in this phase are described in the following sections. We selected those activities because they are easy to implement and, we have found, receive overall patient acceptability.

For a detailed understanding of strategies used in Phase II of CBT for preventing suicide, see Related Resources. In addition, the book Choosing to live: How to defeat suicide through cognitive therapy11 can serve as a self-help guide for patients to follow through with CBT skill-building strategies.

Sample activity #1: Construct a ‘hope box.’ One activity that you can use to help a patient cope with suicide-activating core beliefs (eg, “My life is worthless”) involves construction of a so-called hope box. The box helps the patient directly challenge his extreme distress, by being reminded of previous successes, positive experiences, and reasons for living. The process of constructing a hope box allows the patient to work on modifying his problematic core beliefs (eg, worthlessness, helplessness, incapable of being loved).

It can be helpful to have the patient construct his hope box during a session, to ensure that everything that is put in the box is truly helpful and personalized. Items included vary from patient to patient, and might consist of pictures of loved ones, a favorite poem, a prayer, coping cards (see next section), or all of these. For example, one of our patients chose to include a picture of herself in her early 20s as a reminder of a positive, fulfilling time in her life; this gave her hope that it is possible to experience those feelings again.

Bush et alb at the National Center for Telehealth and Technology have developed a Virtual Hope Box, a free mobile application for tablets and smartphones (compatible with Android and iOS operating systems) that patients can use under the guidance of their practitioner.

bwww.t2.health.mil/apps/virtual-hope-box

Sample activity #2: Generate coping cards. Effective problem-solving skills can be promoted by having the patient construct coping cards —wallet-size cards generated collaboratively in session. Coping cards are note cards that a patient keeps nearby to cope better during a difficult situation. They provide an easily accessible way to jump-start adaptive thinking during a suicidal crisis. The patient is encouraged to use coping cards to practice adaptive thinking even when not in a crisis.