Chronic pain and depression: Treatment of 2 culprits in common

Selected antidepressants address both disorders. Non-drug therapies can be useful adjuncts.

Benzodiazepines should be avoided as a routine treatment for comorbid anxiety and pain, because these agents can produce sedation and cognitive interference, and carry the potential for dependence.

Fatigue. In patients who, in addition to pain and depression, complain of fatigue, an activating agent such as milnacipran or adjunct bupropion might be preferable to other agents. Modafinil has been shown to be a well-tolerated and potentially effective augmenting agent for antidepressants when fatigue and sleepiness are present as residual symptoms22; consider them as adjuncts when managing patients who have chronic pain and depression that manifests as excessive sleepiness and/or fatigue.

Cognitive complaints. We have noted that disturbances of cognition are common in patients with depression and chronic pain, and that cognitive dysfunction might improve after antidepressant treatment.

Studies suggest that SSRIs, duloxetine, and other antidepressants, such as bupropion, might exert a positive effect on learning, memory, and executive function in depressed patients.23 Beneficial effects of antidepressants may be “pseudo-specific,” however—that is, predominantly a reflection of overall improvement in mood, not on specific amelioration of the cognitive disturbance.

Vortioxetine has shown promise in improving cognitive function in adults with MDD; its cognitive benefits are largely independent of its antidepressant effect.24 The utility of vortioxetine in chronic pain patients has not been studied, but its positive impact on mood, anxiety, sleep, and cognition might make it a consideration for patients with comorbid depression—although it is uncertain at this time whether putative noradrenergic activity makes it suitable for use in chronic pain disorders.

Last, avoid TCAs in patients who have cognitive complaints. These agents have anticholinergic effects that can have an adverse impact on cognitive function.

Cautions: Drug−drug interactions, suicide risk, disrupted sleep

Avoiding drug−drug interactions is an important consideration when treating comorbid disorders. Many chronic pain patients take over-the-counter or prescribed nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for analgesia; these agents can increase the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding when they are combined with an SSRI or an SNRI.

The use of the opioid tramadol with an SNRI or a TCA is discouraged because of the risk of serotonin syndrome.

Combining a sedating antidepressant, such as a TCA, with gabapentin or pregabalin can increase the risk of CNS depression and psychomotor impairment, especially in geriatric patients. An opioid analgesic is likely to amplify these effects.

Suicidal ideation is not uncommon in patients with chronic pain and depression. To minimize the risk of suicide in patients with a chronic pain disorder, you should ensure optimal pain control by combining the most efficacious analgesic agent with psychotherapeutic interventions and optimal antidepressant treatment. Furthermore, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) (see the discussion below) might not only improve pain coping skills, but also ameliorate catastrophizing, anxiety, and concomitant sleep disturbance.

Complaints of sleep disturbance and anxiety can compound the risk of suicide in a chronic pain patient. When possible, these complex patients should be treated by a multidisciplinary team that includes a pain management specialist, psychotherapist, and primary care clinician. It is important to strengthen the clinician−patient relationship to facilitate close monitoring of symptoms and to provide a trusting environment in which patients feel free to discuss thoughts of suicide or self-harm. For such patients, prescribing opiates and TCAs in small quantities is a prudent action.

When a patient struggles with suicidal thoughts, his (her) family might need to dispense these medications. Most important, if a patient is actively suicidal, consider referral to an inpatient facility or intensive outpatient program, where aggressive treatment of depressive symptoms and intensive monitoring and support can be provided.25

Usefulness of non-drug interventions

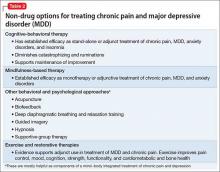

There is, of course, a diversity of non-drug treatments for MDD and for chronic pain; discussion here focuses primarily on modalities with established efficacy in both disease states (Table 2). On rare occasions, non-drug treatments can constitute a stand-alone approach; most often, they are incorporated into a multimodal treatment plan or applied as an adjunct intervention.26

Psychotherapy. The most robust evidence supports the use of CBT in addressing MDD and chronic pain—occurring individually and comorbidly.26-28 Efficacy is well established in MDD, as monotherapy and adjunct treatment, spanning acute and maintenance phases.

Furthermore, CBT also has support from randomized trials, meta-analyses, and treatment guidelines, either as monotherapy or co-therapy for both short-term relief and long-term pain reduction. Additionally, CBT has demonstrated value for relieving pain-related disability.26,28

Combination of a special form of CBT, rumination-focused CBT with ongoing pharmacological therapy over a 26-week period in a group of medication-refractory MDD patients produced a remission rate of 62%, compared with 21% in a treatment-as-usual group.29 This is of particular interest in chronic pain patients, because rumination-related phenomena of pain catastrophizing and avoidance facilitate a transition from acute to chronic pain, while augmenting pain severity and associated disability.30