Chronic pain and depression: Treatment of 2 culprits in common

Selected antidepressants address both disorders. Non-drug therapies can be useful adjuncts.

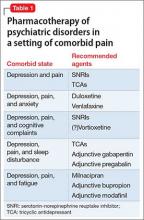

Patients who have chronic pain and those with a major depressive disorder (MDD) share clinical features, including fatigue, cognitive complaints, and functional limitation. Sleep disturbance and anxiety are common with both disorders. Because pain and depression share common neurobiological pathways (see Part 1 of this article in the February 2016 issue and at CurrentPsychiatry.com) and clinical manifestations, you can use similar strategies and, often, the same agents to treat both conditions when they occur together (Table 1).

What are the medical options?

Antidepressants. Using an antidepressant to treat chronic pain is a common practice in primary care and specialty practice. Antidepressants that modulate multiple neurotransmitters appear to be more efficacious than those with a single mechanism of action.1 Convergent evidence from preclinical and clinical studies supports the use of serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) as more effective analgesic agents, compared with the mostly noradrenergic antidepressants, which, in turn, are more effective than selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).2 The mechanism of the analgesic action of antidepressants appears to rely on their inhibitory effects of norepinephrine and serotonin reuptake, thereby elevating the performance of endogenous descending pain regulatory pathways.3

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), primarily amitriptyline, nortriptyline, and desipramine, have the advantage of years of clinical experience and low cost. Their side effect burden, however, is higher, especially in geriatric patients. Dose-dependent side effects include sedation, constipation, dry mouth, urinary retention, and orthostatic hypotension.

TCAs must be used with caution in patients with suicidal ideation because of the risk of a potentially lethal intentional overdose.

The key to using a TCA is to start with a low dosage, followed by slow titration. Typically, the dosages of TCAs used in clinical trials that focused on pain have been lower (25 to 100 mg/d of amitriptyline or equivalent) than the dosage typically necessary for treating depression; however, some experts have found that titrating TCAs to higher dosages with an option of monitoring serum levels may benefit some patients.4

SNRIs are considered first-line agents for both neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia. Duloxetine has been shown to be effective in both conditions5; venlafaxine also has shown efficacy in neuropathic pain.6 Milnacipran, another SNRI that blocks 5-HT, and norepinephrine equally and exerts a mild N-methyl-D-aspartate inhibition, has proven efficacy in fibromyalgia.7,8

SSRIs for alleviating central pain or neuropathic pain are supported by minimal evidence only.9 A review of the effectiveness of various antidepressants on pain in diabetic neuropathy concluded that fluoxetine was no more effective than placebo.10,11 Schreiber and Pick11 evaluated the antinociceptive properties of several SSRIs and offered the opinion that fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, and citalopram were, at best, weak antinociceptors.

Opioids. Data on the long-term benefits of opioids are limited, except for use in carefully selected patients; in any case, risk of abuse, diversion, and even death with these agents is quite high.12 Also, there is evidence that opioid-induced hyperalgesia might limit the usefulness of opioids for controlling chronic pain.13

Gabapentin and pregabalin, both anticonvulsants, act by binding to the α-2-σ subunit of voltage-gated calcium channels within the CNS.14 By reducing calcium influx at nerve terminals, the drugs diminish the release of several neurotransmitters, including glutamate, noradrenaline, and substance P. This mechanism is thought to be the basis for the analgesic, anticonvulsant, and anxiolytic effects of these drugs.15

Gabapentin and pregabalin have been shown to decrease pain intensity and improve quality of life and function in patients with neuropathic pain conditions. Pregabalin also has shown efficacy in treating central neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia.16

Added benefits of these drugs is that they have (1) a better side effect profile than TCAs and (2) fewer drug interactions when they are used as a component of combination therapy. Pregabalin has the additional advantage of less-frequent dosing, linear pharmacokinetics, and a predictable dose-response relationship.17

Addressing other comorbid psychiatric conditions

Sleep disturbance is common among patients with chronic pain. Sleep deprivation causes a hyperexcitable state that amplifies the pain response.18

When a patient presents with chronic pain, depression, and disturbed sleep, consider using a sedating antidepressant, such as a TCA. Alternatively, gabapentin or pregabalin can be added to an SNRI; anticonvulsants have been shown to improve quality of sleep.19 Cognitive-behavioral interventions targeting sleep disturbance may be a helpful adjunct in these patients.20

When anxiety is comorbid with chronic pain, antidepressants with proven efficacy in treating anxiety disorders, such as duloxetine or venlafaxine, can be used. When chronic pain coexists with a specific anxiety disorder (social anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder), an SSRI might be more advantageous than an SNRI,21 especially if it is combined with a more efficacious analgesic.