The Social Worker’s Role in Delirium Care for Hospitalized Veterans

Delirium, or the state of mental confusion that may occur with physical or mental illness, is common, morbid, and costly; however, of the diagnosed cases, delirium is mentioned in hospital discharge summaries only 16% to 55% of the time.1-3

Social workers often coordinate care transitions for hospitalized older veterans. They serve as interdisciplinary team members who communicate with VA medical staff as well as with the patient and family. This position, in addition to their training in communication and advocacy, primes social workers for a role in delirium care and provides the needed support for veterans who experience delirium and their families.

Background

Delirium is a sudden disturbance of attention with reduced awareness of the environment. Because attention is impaired, other changes in cognition are common, including perceptual and thought disturbances. Additionally, delirium includes fluctuations in consciousness over the course of a day. The acute development of these cognitive disturbances is distinct from a preexisting chronic cognitive impairment, such as dementia. Delirium is a direct consequence of underlying medical conditions, such as infections, polypharmacy, dehydration, and surgery.4

Delirium subtypes all have inattention as a core symptom. In half of the cases, patients are hypoactive and will not awaken easily or participate in daily care plans readily.4 Hyperactive delirium occurs in a quarter of cases. In the remaining mixed delirium cases patients fluctuate between the 2 states.4

Delirium is often falsely mistaken for dementia. Although delirium and dementia can present similarly, delirium has a sudden onset, which can alert health care professionals (HCPs) to the likelihood of delirium. Another important distinction is that delirium is typically reversible. Symptom manifestations of delirium may also be confused with depression.

Related: Delirium in the Cardiac ICU

Preventing delirium is important due to its many negative health outcomes. Older adults who develop delirium are more likely to die sooner. In a Canadian study of hospitalized patients aged ≥ 65 years, 41.6% of the delirium cohort and 14.4% of the control group died within 12 months of hospital admission.5 The death rate predicted by delirium in the Canadian study was comparable to the death rate of those who experience other serious medical conditions, such as sepsis or a heart attack.6

Those who survive delirium experience other serious outcomes, such as a negative impact on function and cognition and an increase in long-term care placement.7 Even when the condition resolves quickly, lasting functional impairment may be evident without return to baseline functioning.8 Hospitalized veterans are generally older, making them susceptible to developing delirium.9

Prevalence

Delirium can result from multiple medical conditions and develops in up to 50% of patients after general surgery and up to 80% of patients in the intensive care unit.10,11 From 20% to 40% of hospitalized older adults and from 50% to 89% of patients with preexisting Alzheimer disease may develop delirium.12-15 The increasing number of aging adults who will be hospitalized may also result in an increased prevalence of delirium.1,16

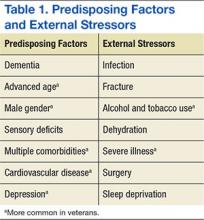

Delirium is a result of various predisposing and precipitating factors.1 Predisposing vulnerabilities are intrinsic to the individual, whereas precipitating external stressors are found in the environment. External stressors may trigger delirium in an individual who is vulnerable due to predisposing risk. The primary risk factors for delirium include dementia, advanced age, sensory impairment, fracture, infection, and dehydration (Table 1).12

Predisposing factors for delirium, such as age and sex, lifestyle choices (alcohol, tobacco), and chronic conditions (atherosclerosis, depression, prior stroke/transient ischemic attack) are more prevalent in the veteran population.9,17-20 In 2011, the median age for male veterans was 64 and the median age for male nonveterans was 41. Of male veterans, 49.9% are aged ≥ 65 years in comparison with 10.5% of the nonveteran male population.21 Veterans also have higher rates of comorbidities; a significant risk factor for delirium.20 A study by Agha and colleagues found that veterans were 14 times more likely to have 5 or more medical conditions than that of the general population.9 In a study comparing veterans aged ≥ 65 years with their age matched nonveteran peers, the health status of the veterans was poorer overall.22 Veterans are more likely to have posttraumatic stress disorder, which can increase the risk of postsurgery delirium and dementia, a primary risk factor for delirium.23-26

Delirium Intervention

Up to 40% of delirium cases can be prevented.27 But delirium may remain undetected in older veterans because its symptoms are sometimes thought to be the unavoidable consequences of aging, dementia, preexisting mental health conditions, substance abuse, a disease process, or the hospital environment.28 Therefore, to avoid the negative consequences of delirium, prevention is critical.28