Sarcopenia and the New ICD-10-CM Code: Screening, Staging, and Diagnosis Considerations

Sarcopenia is an age-related loss of skeletal muscle that may result in diminished muscle strength and functional performance. The prevalence of sarcopenia varies based on the cohort and the assessment criteria. According to the Health Aging and Body Composition (ABC) study, the prevalence of sarcopenia in community-dwelling older adults is about 14% to 18%, whereas the estimate may exceed 30% for those in longterm care.1,2 This geriatric syndrome may disproportionately affect veterans given that they are older than the civilian population and may have disabling comorbid conditions associated with military service.3

Recently, there has been a call to action to systematically address sarcopenia by interdisciplinary organizations such as the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO) and the International Working Group on Sarcopenia (IWGS).4,5 This call to action is due to the association of sarcopenia with increased health care costs, higher disability incidence, and elevated risk of mortality.6,7 The consequences of sarcopenia may include serious complications, such as hip fracture or a loss of functional independence.8,9 The CDC now recognizes sarcopenia as an independently reportable medical condition. Consequently, physicians, nurse practitioners (NPs), and other associated health professionals within the VA will need to better understand clinically viable and valid methods to screen and diagnose this geriatric syndrome.

The purpose of this paper is to inform practitioners how sarcopenia screening is aided by the new ICD-10-CM code and briefly review recent VA initiatives for proactive care. Additional objectives include identifying common methods used to assess sarcopenia and providing general recommendations to the VHA National Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention (NCP) concerning the management of sarcopenia.

Addressing Sarcopenia

While the age-related decline in muscle size and performance has long been recognized by geriatricians, sustained advocacy by several organizations was required to realize the formal recognition of sarcopenia. Aging in Motion (AIM), a coalition of organizations focused on advancing research and treatment for conditions associated with age-related muscle dysfunction, sought the formal recognition of sarcopenia. The CDC established the ICD-10-CM code for sarcopenia in October of 2016, which allowed the syndrome to be designated as a primary or secondary condition.10

The ubiquitous nature of agerelated changes in muscle and the mandate to engage in proactive care by all levels of VA leadership led to the focus on addressing sarcopenia. The recognition of sarcopenia by the CDC comes at an opportune time given recent VA efforts to transform itself from a facilitator mainly of care delivery to an active partner in fostering the health and well-being of veterans. Initiatives that are emblematic of this attempt to shift the organizational culture across the VHA include establishing the VA Center for Innovation (VACI) and issuing guidance documents, such as the Blueprint for Excellence, which was introduced in 2014 by then VA Secretary Robert McDonald.11,12 Many of the following Blueprint themes and strategies potentially impact sarcopenia screening and treatment within the VA:

- Delivering high-quality, veteran-centered care: A major Blueprint theme is attaining the “Triple Aims” of a health care system by promoting better health among veterans, improving the provision of care, and lowering costs through operational efficiency. The management of sarcopenia has clear clinical value given the association of age-related muscle loss with fall risk and decreased mobility.13 Financial value also may be associated with the effort to decrease disability related to sarcopenia and the use of a team approach featuring associated health professionals to help screen for this geriatric syndrome.14,15 (Strategy 2)

- Leveraging health care informatics to optimize individual and population health outcomes: The inclusion of the most basic muscle performance and functional status measures in the electronic medical record (EMR), such as grip strength and gait speed, would help to identify the risk factors and determinants of sarcopenia among the veteran population. (Strategy 3)

- Advancing personalized, proactive health care that fosters a high level of health and well-being: The long-term promotion of musculoskeletal health and optimal management of sarcopenia cannot be sustained through episodic medical interactions. Instead, a contemporary approach to health services marked by the continuous promotion of health education, physical activity and exercise, and proper nutrition has demonstrated value in the management of chronic conditions.16,17 (Strategy 6)

The new sarcopenia ICD-10-CM code along with elements of the VHA Blueprint can serve to support the systematic assessment and management of veterans with age-related muscle dysfunction. Nevertheless, renewed calls for health promotion and screening programs are often counterbalanced by the need for cost containment and the cautionary tales concerning the potential harms or errors associated with some forms of medical screening. The American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation has spearheaded the Choosing Wisely campaign to raise awareness about excessive medical testing. However, the Institute of Medicine has linked the provision of quality health care to a diagnostic process that is both timely and accurate.18 Careful consideration of these health care challenges may help guide practitioners within the VA concerning the screening and diagnosis of sarcopenia.

Sarcopenia Assessment

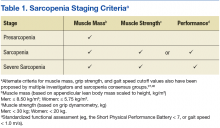

Sarcopenia can have several underlying causes in some individuals and result in varied patterns of clinical presentation and differing degrees of severity. The European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People first met in 2009 and used a consensus-based decision-making process to determine operational definitions for sarcopenia and create a staging algorithm for the syndrome.19 This consensus group developed a conceptual staging model with 3 categories: presarcopenia, sarcopenia, and severe sarcopenia (Table 1). The impetus for sarcopenia staging was the emerging research findings suggesting that lean body mass (LBM) alone did not provide a high degree of clinical value in outpatient settings due to the nonlinear relationship between LBM and muscle function in older adults.20,21 Using the consensus model approach, an individual is classified as sarcopenic on presenting with both low LBM and low muscle function.

Screening: A Place to Start

Findings from the Health ABC Study suggested that older adults who maintained high levels of LBM were less likely to become sarcopenic. Whereas, older adults in the cohort with low levels of LBM tended to remain in a sarcopenic state.6 Consequently, the early detection of sarcopenia may have important health promotion implications for older adults. Sarcopenia is a syndrome with a continuum of clinical features; it is not a disease with a clear or singular etiololgy. Therefore, the result of the screening examination should identify those who would most benefit from a formal diagnostic assessment.

One approach to screening for sarcopenia involves the use of questionnaires, such as the SARC-F (sluggishness, assistance in walking, rise from a chair, climb stairs, falls), which is a brief 5-item questionnaire with Likert scoring for patient responses.13 In a cohort of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) participants, SARC-F scores ≥ 4 were associated with slower gait speed, lower strength, and an increased likelihood of hospitalization within a year of the test response.22 However, rather than stratify patients by risk, the SARC-F exhibits a high degree of test specificity regarding the major consensus-based sarcopenia classification criteria (specificity = 94.2% to 99.1%; sensitivity = 3.8% to 9.9%).13 Given the known limitations of screening tools with low sensitivity, organizations such as the ESCEO have recommended supplementing the SARC-F questionnaire with other forms of assessment.4 Supplements to the screening examination may range from the use of “red flag” questions concerning changes in nutritional status, body weight, and physical activity, to conducting standard gait speed and grip-strength testing.4,19,23

Performance-based testing, including habitual gait speed and grip-strength dynamometry, also may be used in both the screening and classification of sarcopenia.2 Although walking speed below 1.0 m/s has been used by the IWGS as a criterion to prompt further assessment, many people within the VA health care system may have gait abnormalities independent of LBM status, and others may be nonambulatory.24,25 As a result, grip-strength testing should be considered as a supplementary or alternate screening assessment tool.26,27

Hand-grip dynamometry is often used diagnostically given its previous test validation, low expense, and ease of use.23 Moreover, recent evidence suggests that muscle strength surpasses gait speed as a means of identifying people with sarcopenia. Grip strength is associated with all-cause mortality, even when adjusting for age, sex, and body size,28 while slow gait speed (< .82 m/s) has a reported sensitivity of 63% and specificity of 70% for mortality in population-based studies involving older adults.29