Preventing and treating acute gout attacks across the clinical spectrum: A roundtable discussion

ACUTE FLARES IN THE SETTING OF PROPHYLAXIS AND URATE LOWERING: WHAT TO DO?

Dr. Mandell: It sounds like most of us would treat patients prophylactically with colchicine for a while after an attack, certainly after several attacks, and then continue on chronic low-dose colchicine during the introduction and adjustment of the urate-lowering therapy that constitutes comprehensive gout treatment. Yet some patients will still have flares. So how does this baseline low-dose colchicine prophylaxis—a 0.6-mg tablet once or twice daily—influence your choice of therapy for those attacks? Do you bump up the colchicine dose, or do you absolutely avoid increasing the colchicine?

Dr. Sundy: I wouldn’t absolutely avoid an increase, but I would tend not to adjust it. I would maintain the dose and add a different agent on top of it—an NSAID or corticosteroid—to manage the acute attack. In general, if a patient is on regular colchicine prophylaxis, the assumption is that they have sufficient renal function to support that use, so such a patient may do fine with an NSAID.

Dr. Simkin: I trust we all agree that it’s critically important to continue the urate-lowering therapy the patient is taking if he suffers an attack. The same thing pertains to the prophylactic regimen. Both of these components should continue through the flare, but I agree that we usually want to add something to treat a flare, and it should be something the patient has on hand and can take without needing to talk to his physician if it’s the middle of the night.

Dr. Mandell: So I’m hearing that most of us would add something else for the short term on top of the prophylactic colchicine dose when a flare developed rather than increasing the colchicine dose.

Dr. Simkin: Yes, although one exception I’d be comfortable with is the example we discussed earlier of the patient who has found that taking an extra colchicine pill or two can help abort or diminish a flare without causing diarrhea.

Dr. Mandell: We cannot extrapolate the AGREE data to support a short-course regimen for an acute attack in patients who are already on chronic colchicine for prophylaxis.

PROPHYLAXIS IN THE PERIOPERATIVE SETTING

Dr. Mandell: Admission to the hospital for acute medical or surgical reasons is not infrequently associated with gout flares. Jim, have we in the rheumatologic community made it clear that chronic colchicine prophylaxis and urate-lowering therapy should ideally be continued when patients with gout are hospitalized for any reason, or is it a reflex for these drugs be held?

Dr. Pile: I think there’s a general appreciation, at least in the hospital medicine community, that these therapies should be continued in that situation. My sense is that these prophylactic gout therapies are viewed by most hospitalists as somewhat analogous to beta-blockers for chronic heart failure, which are understood to be necessary to continue when a patient is admitted with an acute exacerbation of heart failure. I don’t have data to support this contention, however.

Dr. Edwards: My experience suggests that discontinuing urate-lowering therapy during an acute gout attack is a common mistake in general practice. I think that’s been demonstrated in surveys of primary care physicians. And when the uratelowering therapy is stopped, the attack is often prolonged and made worse. Widespread misperception about this remains—it’s a big problem.

Dr. Mandell: Based on educational lectures I’ve given to primary care audiences, I agree with Larry. If I present a case question on a scenario like this, many physicians in the audience will anonymously indicate via the audience response system that they would stop a patient’s allopurinol if an acute attack occurred.

Let’s turn to the scenario of a patient who’s admitted for surgery—elective or emergent—who has a history of gout and is on prophylaxis. What’s the general routine in managing these medications in patients who are going to surgery?

Dr. Pile: In my preoperative consultations I’ve always stressed to gout patients and their surgeons that the postoperative period is a high-risk setting for acute exacerbation of gout. My routine recommendation in this setting is that patients continue any of their goutrelated medications through the postoperative period, but that often doesn’t happen. All sorts of medications are inappropriately stopped perioperatively, including statins and beta-blockers in addition to colchicine or allopurinol. Something I haven’t done routinely is to recommend introducing prophylaxis in the postoperative period for patients who were not already receiving it. Is that something you consider doing, given the likelihood of postoperative flare?

Dr. Edwards: It’s important to appreciate the reasons why gout flares postoperatively. It has a lot to do with why uric acid levels go up postoperatively: fluid changes, starvation, ketosis for any reason, lactic acidosis—these all cause pretty remarkable changes in systemic pH, which certainly is a trigger for that. The perioperative state also changes the exchange of uric acid in the kidney so that there is greater accumulation, and anything that rapidly bumps up serum urate levels while also creating a change in the pH is a setup for flares. So any recommendations about whether or not to give prophylaxis have a lot to do with the anticipated impact of the surgery on all of those physiologic parameters.

Dr. Sundy: As rheumatologists we’re usually called after the fact, so I can’t say I’ve given the issue of prophylaxis in the perioperative setting a lot of thought. I would add that patients who are undergoing cardiac catheterization, especially with stenting procedures that may require a large dye load, are another group that tends to be at increased risk of flare, especially in the setting of acute myocardial infarction.

Dr. Edwards: They could get a subtle change in renal function related to the dye load that isn’t throwing them into acute tubular necrosis or acute renal failure but is enough to reduce elimination of urate for long enough that they get this bump of uric acid that triggers the flare.

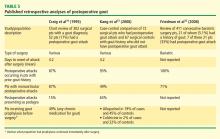

Dr. Mandell: The retrospective analyses of perioperative gout show that patients who come in with lower urate to begin with are less likely to have flares,33 which suggests that perioperative flares are less likely in patients who have been better controlled and managed. The question of whether to introduce prophylaxis at admission, given the likelihood of postoperative flare, hasn’t been studied formally. Despite this absence of data, I would be comfortable introducing colchicine at a low dose for prophylaxis in this setting, especially in a patient who has had frequent or recent attacks. The major exception would be for patients undergoing bowel surgery or similar procedures, since colchicine’s potential to cause diarrhea and other GI side effects is a main concern with its perioperative use. But a study of prophylactic colchicine before surgery in a “high-risk” population is a trial begging to be done. The challenge is that because the event rate is low, the sample size needed would be so large as to potentially make the study impossible.

Dr. Pile: One issue I encounter from time to time as a preoperative consultant involves patients who should be on chronic urate-lowering therapy but are not. Obviously, when I’m seeing them 7 days before surgery it’s not the time to contemplate doing anything besides perhaps starting colchicine.

Dr. Mandell: Yes, that would be a time to avoid starting urate-lowering therapy since a drop in serum urate is likely to precipitate gout flares, and that’s something you don’t want to happen in a postoperative setting. So just as we shouldn’t stop urate-lowering therapy preoperatively, we shouldn’t initiate it either. When the patient is already on urate-lowering therapy, it should be continued as close as possible to the time of surgery and restarted immediately thereafter. The fluids that are given perioperatively tend to drop the patient’s urate levels, so we often can get away with the brief window of discontinuation around the time of surgery so long as we restart the allopurinol postoperatively.

Dr. Edwards: There are certain surgeries, such as many cardiac procedures, for which the rooms are kept hypothermic, and that can be one more physiologic stimulus for an attack of gout, particularly in the body’s cooler joints. That’s a setting where podagra might be more common, whereas major abdominal surgery with a lot of bowel ischemia and lactic acidosis may render a wide range of joints more equally susceptible, although there are no data on this question.

Dr. Simkin: I’m not certain that postoperative gout is significantly different from hospitalization gout. If patients who are admitted for medical reasons—for instance, cardiac disease or pneumonia or ketoacidosis—also have an established diagnosis of gouty arthritis, they’re at elevated risk too.

Dr. Mandell: Yes, and that point—that preexisting gout is a major risk factor, whether or not it was known at the time of admission—came through from the studies Jim noted above and our experience. That piece of the history is often not obtained until an attack occurs, although more widespread use of electronic medical records may lessen this problem. It’s frustrating that attacks tend to occur about 4 days after surgery, which is typically around the time of planned discharge.