Preventing and treating acute gout attacks across the clinical spectrum: A roundtable discussion

ACUTE ANALGESIA: ANYTHING MORE THAN AN ADJUNCT?

Dr. Mandell: What about treating gout with acute analgesia alone? Consider a setting where you may want to avoid a drug with anti-inflammatory or antipyretic effects, perhaps in the postoperative period or when coexistent infection is a concern and you want to monitor the fever. Can you get by with using narcotic analgesia alone?

Dr. Sundy: I’m not impressed with that approach. Narcotics can play a role in managing a patient’s pain, but a narcotics-only approach will allow the flare to linger and not address complications of the flare or back-to-work issues. I view analgesics as cotherapy as opposed to single-agent therapy.

Dr. Mandell: Is narcotic analgesia effective even at treating the pain acutely?

Dr. Sundy: No. Gout pain is an exquisitely inflammatory pain, and the key is to tackle that inflammatory response. Analgesics are really just an adjunct.

Dr. Simkin: I totally agree, but they’re an important adjunct that we often overlook.

Dr. Edwards: I’ve been singularly unimpressed with narcotics. Gout is a cytokine-driven process that is intensely inflammatory. It’s like a lot of other types of pain that don’t respond fully to narcotics, such as herpetic neuralgia or uterine pain. Perhaps the benefit of narcotics in gout is their soporific effect—patients sleep through their attack. Yet if you touch the gouty joint or the patient moves it, the pain is just as intense as if the patient weren’t taking anything. So I don’t know that narcotics add anything unless the patient has other causes of pain. I don’t use them at all.

Dr. Sundy: I tend to make the option available to the patient. I say, “Here’s what we need to do to knock down this flare. And here’s something additional you can try for pain; we can see if it helps.” But I’ll emphasize the importance of improving the inflammatory piece.

Getting back to the postoperative setting, we should recognize that a strategy to just ride out a perioperative gout flare with an analgesic medication, perhaps because of concern about the effect of corticosteroids on wound healing or infection, can carry important risks. A patient treated that way will end up bedbound at precisely the time you want him or her to be moving around, so there’s now the risk of postoperative pneumonia and other complications that won’t get documented as complications of gout even though they actually are.

Dr. Mandell: Not to mention the untreated postoperative fever from the crystal-induced attack, which then leads to a work-up looking for DVTs, more blood cultures, and more radiographs, all the while extending the hospital stay and wasting resources. Jim, as a hospitalist, do you still see narcotics used initially as the primary treatment for gout flares in the hospital?

Dr. Pile: It depends on which hat I’m wearing. If I’m the hospitalist and the patient’s on my service, usually my antennae are up for the appearance of gout in the hospital, and the house staff may or may not recognize it if the process starts overnight. When I’m serving as the medical consultant, I sometimes encounter cases where the surgeons don’t recognize a gouty flare when it first appears, and I’ve had multiple patients in whom gout-induced postoperative fever triggers a consultation. In the latter case, it’s not uncommon to see narcotics being used in an attempt to treat gouty pain.

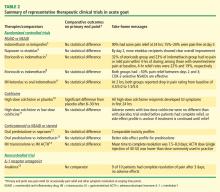

RELATIVE DRUG EFFICACY FOR ACUTE ATTACKS: HOW MUCH DO WE KNOW?

Dr. Edwards: If they’re given early, all of them have good—if not necessarily fast and ideal—effectiveness. The recent AGREE trial of colchicine (Acute Gout Flare Receiving Colchicine Evaluation) assessed pain reduction at 24 hours in patients randomized to three treatment groups: a low-dose colchicine regimen consisting of three 0.6-mg tablets (1.2 mg initially, followed by 0.6 mg 1 hour later); a more traditional high-dose colchicine regimen consisting of eight 0.6-mg tablets (1.2 mg initially, followed by 0.6 mg every hour for 6 hours), and placebo.11 Response, defined as a 50% or greater reduction in pain at 24 hours without rescue medication, was reported in 37.8% of patients in the low-dose colchicine group, 32.7% of patients in the high-dose colchicine group, and 15.5% of placebo recipients.

This is an excellent study that should finally take highdose colchicine for the treatment of acute gout off the table since it offered no improvement in efficacy but was significantly more toxic. However, while 50% improvement in 24 hours is a hard target to achieve, the fact that barely more than a third of subjects hit the target means we should still be looking for more effective approaches.

Dr. Simkin: Similarly, in the first controlled study of colchicine in acute gout, published by Ahern et al in 1987,10 23% of colchicine recipients noted a 50% reduction in their pain at 12 hours after starting treatment. That leaves more than three-quarters with little or no response within 12 hours, and gout is one of the most painful conditions we treat. We’d very much like to help our patients sooner than that. So while there are no head-to-head data comparing colchicine versus NSAIDs versus steroids, my impression too is that oral colchicine is a second-line choice for the acute gout attack.

Dr. Sundy: When we try to understand this literature, it’s important to look closely at how patients were ascertained. The AGREE trial evaluated patients who were enrolled when they were asymptomatic; they were given study medication and instructed on how to start it once a flare began. In contrast, most of the well-controlled NSAID trials captured patients as they came in with a flare, and they had to have had the flare no longer than 48 hours. I believe there’s a big difference between having had a flare for 12 hours versus 48 hours—and even as long as 72 hours in some corticosteroid trials. The longer the clock has been allowed to tick before treatment is started, the harder it is to achieve rapid symptom reduction.

Dr. Mandell: Obviously it’s difficult to compare between studies, but it’s interesting that in a study of the COX-2 inhibitor etoricoxib versus indomethacin,7 one of the largest studies of NSAID therapy for acute gout, approximately one-third of patients taking etoricoxib reported no pain or mild pain within 4 hours. This very rapid pain control is what we really want, since pain is the concern, along with eventual complete resolution, of course. So there really may be value in having something that has analgesic as well as anti-inflammatory effect, to Peter’s earlier point. Tackling both the pain and the inflammation that’s causing the pain certainly makes sense.

Dr. Edwards: Yes, and that etoricoxib study was designed the way people often are treated, with the unfortunate delay before the doctor is seen and the medication is started. The AGREE trial is how I hope everybody would be treated regardless of what they’re treated with. We’re probably never going to see a good head-to-head trial among the three main types of drugs we use for acute gout—the unpredictability of flares makes it extremely difficult.

Dr. Pile: I’m curious whether or not you, as rheumatologists who specialize in gout, are surprised by the results of AGREE. My experience with colchicine over time has been more favorable than what’s suggested by AGREE.

Dr. Edwards: How do you use the colchicine?

Dr. Pile: For more than a decade I’ve been using 0.6 mg three times daily. I thought that practice was unusual until I recently read the AGREE study and realized that a lot of you have been using that regimen for a while.

Dr. Mandell: Some gout patients will take a colchicine tablet when they feel the wisp of an attack coming on and it immediately will stop the attack. That gets to the lore that if you treat a flare very early on, you may be able to abort and treat an attack very quickly. Years ago, however, I was involved in an analysis of 100 patients treated with intravenous (IV) colchicine, and we found that treatment response was unaffected by whether patients were treated early or after a delay of 48 hours. I believe colchicine behaves like a different drug when given IV—and the IV form has since been withdrawn from the market for safety concerns—but this underscores that individual responses to various agents are quite unique. I think there are some patients who are exquisitely sensitive to colchicine, while others are exquisitely sensitive to an NSAID, and so on. This means we’d need a very large sample size to tease out that variation in a trial, and that’s not likely to happen.

Dr. Edwards: I too have had gout patients who tell me they get this premonition of an attack—a feeling that “something just isn’t right”—hours before they actually feel any pain from the attack. A lot of them tell me they’ve learned over time that if they take a colchicine tablet when they get this premonition—or an extra colchicine tablet, as some are on colchicine maintenance therapy (typically one or two tablets a day) plus whatever other background therapy they’re on—they don’t get the flare or the flare is diminished.

Dr. Mandell: I’d like to wrap up this portion by getting your sense of whether there’s a difference in efficacy for treating acute attacks among the drug classes we’ve discussed.

Dr. Edwards: I believe the IL-1 inhibitors are probably the most potent agents for aborting a gout attack, followed by steroids, which I think have a leg up on both colchicine and NSAIDs. The latter two options probably are equally effective in aborting an acute attack.

Dr. Sundy: Yes, I would rank them the same way.