Preventing and treating acute gout attacks across the clinical spectrum: A roundtable discussion

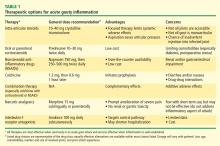

GENERAL APPROACH TO THE ACUTE GOUT ATTACK

Dr. Mandell: Let’s return to the patient who presents with an acutely swollen, painful joint. Let’s say gout is diagnosed with confidence, supported either by synovial fluid analysis or by the overall clinical details. What are your general considerations, Jim, for initial treatment in the hospital?

Dr. Mandell: We’ll come back and talk about each of these drug classes specifically, but what do my fellow rheumatologists tend to reach for as first-choice therapy?

Dr. Simkin: My thinking is very similar to Jim’s. As far as NSAIDs are concerned, so many of our patients have significant renal compromise that it is absolutely mandatory that we know what a patient’s renal function is before we treat acute gout with NSAIDs. I’ve seen more catastrophes from the use of NSAIDs in patients with renal compromise than from any other gout treatment scenario. So I probably wind up using steroids more often, but in the hospital setting you often have to deal with a surgeon who doesn’t want to use steroids. In such a case, if the patient also has renal problems, an agent that has entered the picture in our hospital is the interleukin-1 (IL-1) receptor antagonist anakinra, given in daily subcutaneous injections of 100 mg. When a patient is hospitalized for gout, it’s his severely painful joint that’s keeping him from going home, and in this situation anakinra in fact becomes a relatively inexpensive option, despite its absolute cost, when compared with the cost of the hospital bed.

Dr. Mandell: I think that’s the first time I’ve heard “anakinra” and “inexpensive” used in the same sentence.

Dr. Simkin: Of course biologics are terribly expensive, but so is hospitalization, and hospitals are bad places. We want to get our patients home, and in our experience this has been a very useful way to make that happen sooner.

Dr. Pile: I agree that an emphasis on hospital throughput is incredibly important. For the hospitalized patient with gout that’s preventing ambulation, that’s the issue that must be addressed before discharge is possible. Certainly the agent with the fastest onset of action is going to be very attractive.

Dr. Edwards: All of these agents for acute gout have a relatively fast onset of action if they’re given early in the disease process. Once you get out to a day and a half from the onset of symptoms or beyond, you’re fighting an uphill battle in terms of making a difference in the natural course of the attack. I believe that’s true of all three of the medication classes that are typically used.

My approach to the initial therapy choice is highly individualized, depending on what the patient’s been on before. If they’ve been on maintenance colchicine to prevent flares and then they flare, I usually won’t use colchicine for the acute attack; I will go with a steroid or an NSAID. If they’ve been on NSAIDs as preventive therapy and they flare, I might try low-dose colchicine for the flare or use steroids. In cases of a prolonged course, where the patient is in the hospital and it’s 3 or 4 days since symptom onset and a steroid taper or a trial of colchicine has failed, I’ve been very impressed with the ability of anakinra to suddenly bring the attack to a halt. Like Peter, I am on the cusp of looking at acute treatments a little differently, although there still aren’t a lot of data on IL-1 inhibition in this setting.

Dr. Sundy: There are data showing that a gout flare adds about 3 days to the hospital stay,4 so that’s a huge burden that intervention with IL-1 inhibition can really help to address.

Dr. Mandell: I think we’ve seen a trend over time toward corticosteroid therapy becoming more common, particularly in hospitalized patients. I think that’s partially related to more widespread use of appropriate deep vein thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis, which means that more patients are on anticoagulant therapy, which is one more reason to shy away from NSAIDs, particularly the nonselective ones, in the hospital setting. Do you sense that trends in the outpatient setting have shifted, or do most clinicians still reach for NSAIDs?

Dr. Sundy: I think most people still reach for the NSAID, but it really depends on the comorbidities. I sense we’re seeing chronic kidney disease in a greater proportion of patients, and that’s probably creating a shift toward a bit more corticosteroid use. I like to reach for an NSAID as first-line therapy, but we really have to understand our patient’s overall comorbidity profile, including renal function, before doing so, as Peter said.

Dr. Edwards: I think NSAIDs are still the most commonly used acute treatment for gout. I used to calm myself when I used them by saying, “It’s only a 7- to 10-day course; how much trouble can you get the patient into?” Well, in that short a time I’ve had patients tip over into congestive heart failure because they had some renal decompensation beforehand and then had another 20% or 25% of their renal function knocked out with the NSAID, and they’d have extra sodium retention. I’ve seen GI bleeds develop in patients over that short a time. I don’t prescribe nonselective cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitors anymore without also giving a proton pump inhibitor for stomach protection. I think that’s becoming a standard of how to use NSAIDs among rheumatologists, and it’s hard to get that stomach protection up and running in the very short time frame of an acute gout attack. So I’m personally tending away from NSAIDs; I use steroids more often and then the IL-1 inhibitor for special cases.

Dr. Mandell: Studies assessing the gastric risk of NSAIDs have shown that a GI bleed can be induced in as little as 2 or 3 days. I agree that there is a trend, at least among rheumatologists, to use a proton pump inhibitor when initiating outpatient NSAID therapy. This combination may still be cost-effective for many patients, as it can speed the return to their usual activities. But even in the outpatient setting steroids are becoming more common than they used to be.

DOSING FOR THE ACUTE ATTACK: BE AGGRESSIVE FROM THE START

Dr. Simkin: Whatever dose of steroids we use in the outpatient setting, I think it’s highly desirable to divide it. Rheumatologists are taught to use a single daily steroid dose in the morning, primarily to spare the adrenal glands. While that makes sense in patients on long-term steroid therapy, such as for lupus, it doesn’t necessarily make sense in gouty arthritis. I’ve seen patients whose gout flared up every night despite taking sufficient prednisone; when they divided the dose, their gout was controlled.

Dr. Mandell: I would generalize that further to stress the importance of using an adequate and aggressive dose of either steroids or NSAIDs for treating acute gout. A common mistake I notice in the community is the use of too low a dose of either steroids or NSAIDs. We should treat aggressively from the start with a full dose of these agents.

Dr. Edwards: Even more than the usual full dose, I would say. Many generalists have a concept of what an analgesic dose of an NSAID is, which is pretty low—in the case of ibuprofen, perhaps 400 mg three times daily. An anti-inflammatory dose is higher—perhaps 800 mg three times daily for ibuprofen. Most of us who’ve used NSAIDs for gout realize that we have to get even a little bolder than that from the start. It can be hard to convince some generalists to exceed what has been their ceiling of comfort for an NSAID, but doing so for the first 24 or 36 hours is important to getting the gout attack under control. Of course, the need for such aggressive dosing is all the more reason to make sure not to use an NSAID in a patient with significant renal disease or other comorbidities for which NSAIDs are problematic.

Dr. Mandell: And all the more reason to provide gastric protection.

Dr. Sundy: I would add that if a clinician is not comfortable using doses that high, that may be a good reason to think about choosing a different initial therapy, be it colchicine or steroids (if the reluctance is with NSAIDs) or NSAIDs (if the reluctance is with steroids).