Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Pulmonary Disease

Case 1 Continued

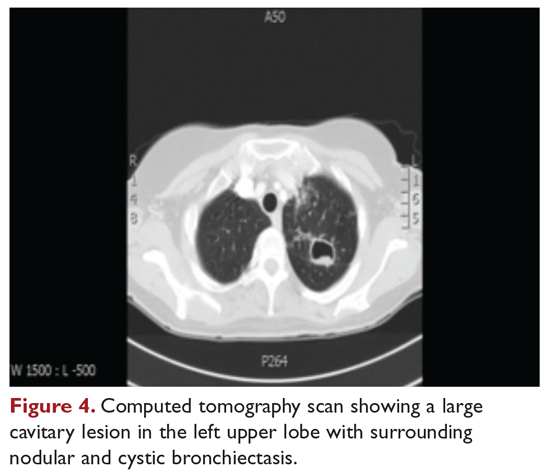

The patient is treated with clarithromycin, rifampin, and ethambutol for 1 year, with sputum conversion after 9 months. In the latter part of her treatment, she experiences decreased visual acuity. Treatment is discontinued prematurely after 1 year due to drug toxicity and continued intolerance to drug therapy. The patient remains asymptomatic for 8 months, and then begins to experience mild to moderate hemoptysis, with increasing cough and sputum production associated with postural changes during exercise. Physical examination overall remains unchanged. Three sputum results reveal heavy growth of MAC, and a CT scan of the chest shows a cavitary lesion in the left upper lobe along with the nodular bronchiectasis (Figure 4).

What are the management options at this stage?

Based on this patient’s continued symptoms, progression of radiologic abnormalities, and current culture growth, she requires re-treatment. With the adverse effects associated with ethambutol during the first round of therapy, the drug regimen needs to be modified. Several considerations are relevant at this stage. Relapse rates range from 20% to 30% after treatment with a macrolide-based therapy.11,34 Obtaining a culture-sensitivity profile is imperative in these cases. Of note, treatment should not be discontinued altogether, but instead the toxic agent should be removed from the treatment regimen. Continuing treatment with a 2-drug regimen of clarithromycin and rifampin may be considered in this patient. Re-infection with multiple genotypes may also occur after successful drug therapy, but this is primarily seen in MAC patients with nodular bronchiectasis.34,35 Patients in whom previous therapy has failed, even those with macrolide-susceptible MAC isolates, are less likely to respond to subsequent therapy. Data suggest that intermittent medication dosing is not effective for patients with severe or cavitary disease or in those in whom previous therapy has failed.36 In this case, treatment should include a daily 3-drug therapy, with an injectable thrice-weekly aminoglycoside. Other agents such as linezolid and clofazimine may have to be tried. Cycloserine, ethionamide, and other agents are sometimes used, but their efficacy is unproven and doubtful. Pyrazinamide and isoniazid have no activity against MAC.

Treatment Failure and Drug Resistance

Treatment failure is considered to have occurred if patients have not had a response (microbiologic, clinical, or radiographic) after 6 months of appropriate therapy or had not achieved conversion of sputum to culture-negative after 12 months of appropriate therapy.11 This occurs in about 40% of patients. Multiple factors can interfere with the successful treatment of MAC pulmonary disease, including medication nonadherence, medication side effects or intolerance, lack of response to a medication regimen, or the emergence of a macrolide-resistant or multidrug-resistant strain. Inducible macrolide resistance remains a potential factor.34-36 A number of characteristics of NTM contribute to the poor response to currently used antibiotics: the organisms have a lipid outer membrane and prefer to adhere to surfaces and form biofilms, which makes them relatively impermeable to antibiotics.37 Also, NTM replicate in phagocytic cells, allowing them to subvert normal cellular defense mechanisms. Furthermore, NTM can display colony variants, whereby single colony isolates switch between antibiotic-susceptible and -resistant variants. These factors have also impeded in development of new antibiotics for NTM infection.37

Recent limited approval of amikacin liposomal inhalation suspension (ALIS) for treatment failure and refractory MAC infection in combination with guideline-based antimicrobial therapy (GBT) is a promising addition to the available treatment armamentarium. In a multinational trial, the addition of ALIS to GBT for treatment-refractory MAC lung disease achieved significantly greater culture conversion rates by month 6 than GBT alone, with comparable rates of serious adverse events.38

Is therapeutic drug monitoring recommended during treatment of MAC pulmonary disease?

Treatment failure may also be drug-related, including poor drug penetration into the damaged lung tissue or drug-drug interactions leading to suboptimal drug levels. Peak serum concentrations have been found to be below target ranges in approximately 50% of patients using a macrolide and ethambutol. Concurrent use of rifampin decreases the peak serum concentration of macrolides and quinolones, with acceptable target levels seen in only 18% to 57% of cases. Whether this alters patient outcomes is not clear.39-42 Factors identified as contributing to the poor response to therapy include poor compliance, cavitary disease, previous treatment for MAC pulmonary disease, and a history of chronic obstructive lung disease. Studies by Koh and colleagues40 and van Ingen and colleagues41 with pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics data showed that, in patients on MAC treatment with both clarithromycin and rifampicin, plasma levels of clarithromycin were lower than the recommended minimal inhibitory concentrations (MIC) against MAC for that drug. The studies also showed that rifampicin lowered clarithromycin concentrations more than did rifabutin, with the AUC/MIC ratio being suboptimal in nearly half the cases. However, low plasma clarithromycin concentrations did not have any correlation with treatment outcomes, as the peak plasma drug concentrations and the peak plasma drug concentration/MIC ratios did not differ between patients with unfavorable treatment outcomes and those with favorable outcomes. This is further compounded by the fact that macrolides achieve higher levels in lung tissue than in plasma, and hence the significance of low plasma levels is unclear; however, it is postulated that achieving higher drug levels could, in fact, lead to better clinical outcomes. Pending specific well-designed, prospective randomized controlled trials, routine therapeutic drug monitoring is not currently recommended, although some referral centers do this as their practice pattern.

Is surgery an option in this case?

The overall 5-year mortality for MAC pulmonary disease was approximately 28% in a retrospective analysis, with patients with cavitary disease at increased risk for death at 5 years.42 As such, surgery is an option in selected cases as part of adjunctive therapy along with anti-MAC therapy based on mycobacterial sensitivity. Surgery is used as either a curative approach or a “debulking” measure.11 When present, clearly localized disease, especially in the upper lobe, lends itself best to surgical intervention. Surgical resection of a solitary pulmonary nodule due to MAC, in addition to concomitant medical treatment, is recommended. Surgical intervention should be considered early in the course of the disease because it may provide a cure without prolonged treatment and its associated problems, and this approach may lead to early sputum conversion. Surgery should also be considered in patients with macrolide-resistant or multidrug-resistant MAC infection or in those who cannot tolerate the side effects of therapy, provided that the disease is focal and limited. Patients with poor preoperative lung function have poorer outcomes than those with good lung function, and postoperative complications arising from treatment, especially with a right-sided pneumonectomy, tend to occur more frequently in these patients. Thoracic surgery for NTM pulmonary disease must be considered cautiously, as this is associated with significant morbidity and mortality and is best performed at specialized centers that have expertise and experience in this field.43

Continue to: Mycobacterium abscessus Complex