Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Pulmonary Disease

Mycobacterium avium Complex

Case Patient 1

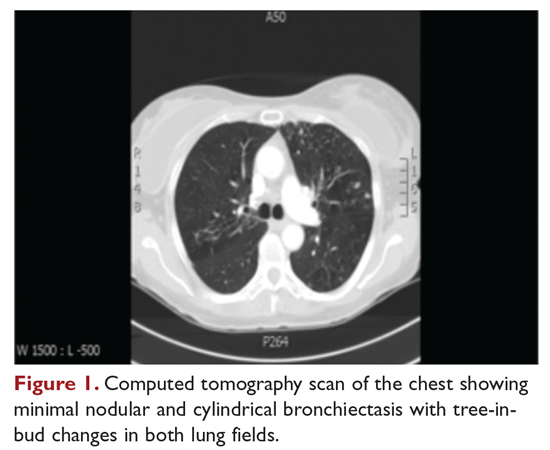

A 48-year-old woman who has never smoked and has no past medical problems, except seasonal allergic rhinitis and “colds and flu-like illness” once or twice a year, is evaluated for a chronic lingering cough with occasional sputum production. The patient denies any other chronic symptoms and is otherwise active. Physical examination reveals no specific findings except mild pectus excavatum and mild scoliosis. Body mass index is 22 kg/m2. Chest radiograph shows nonspecific increased markings in the lower zones. Computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest reveals minimal nodular and cylindrical bronchiectasis in both lungs (Figure 1). No previous radiographs are available for comparison. The patient is HIV-negative. Sputum tests reveal normal flora, and both fungus and acid-fast bacilli smear are negative. Culture for mycobacteria shows scanty growth of MAC in 1 specimen.

What is the clinical presentation of MAC pulmonary disease?

Among NTM, MAC is the most common cause of pulmonary disease worldwide.6 MAC primarily includes 2 species: M. avium and Mycobacterium intracellulare. M. avium is the more important pathogen in disseminated disease, whereas M. intracellulare is the more common respiratory pathogen.11 These organisms are genetically similar and generally not differentiated in the clinical microbiology laboratory, although there are isolated reports in the literature suggesting differences in prevalence, presentation, and prognosis in M. avium infection versus M. intracellulare infection.12

Three major disease syndromes are produced by MAC in humans: pulmonary disease, usually in adults whose systemic immunity is intact; disseminated disease, usually in patients with advanced HIV infection; and cervical lymphadenitis.13 Pulmonary disease caused by MAC may take on 1 of several clinically different forms, including asymptomatic “colonization” or persistent minimal infection without obvious clinical significance; endobronchial involvement; progressive pulmonary disease with radiographic and clinical deterioration and nodular bronchiectasis or cavitary lung disease; hypersensitivity pneumonitis; or persistent, overwhelming mycobacterial growth with symptomatic manifestations, often in a lung with underlying damage due to either chronic obstructive lung disease or pulmonary fibrosis (Table 1).14

Cavitary Disease

The traditionally recognized presentation of MAC lung disease has been apical cavitary lung disease in men in their late 40s and early 50s who have a history of cigarette smoking, and frequently, excessive alcohol use. If left untreated, or in the case of erratic treatment or macrolide drug resistance, this form of disease is generally progressive within a relatively short time and can result in extensive cavitary lung destruction and progressive respiratory failure.15

Nodular Bronchiectasis

The more common presentation of MAC lung disease, which is outlined in the case described here, is interstitial nodular infiltrates, frequently involving the right middle lobe or lingula and predominantly occurring in postmenopausal, nonsmoking white women. This is sometimes labelled “Lady Windermere syndrome.” These patients with M. avium infection appear to have similar clinical characteristics and body types, including lean build, scoliosis, pectus excavatum, and mitral valve prolapse.16,17 The mechanism by which this body morphotype predisposes to pulmonary mycobacterial infection is not defined, but ineffective mucociliary clearance is a possible explanation. Evidence suggests that some patients may be predisposed to NTM lung disease because of preexisting bronchiectasis. Some potential etiologies of bronchiectasis in this population include chronic sinusitis, gastroesophageal reflux with chronic aspiration, α1 antitrypsin deficiency, and cystic fibrosis genetic traits and mutations.18 Risk factors for increased morbidity and mortality include the development of cavitary disease, age, weight loss, lower body mass index, and other comorbid conditions.

This form of disease, termed nodular bronchiectasis, tends to have a much slower progression than cavitary disease, such that long-term follow-up (months to years) may be necessary to demonstrate clinical or radiographic changes.11 The radiographic term “tree-in-bud” has been used to describe what may reflect inflammatory changes, including bronchiolitis. High-resolution CT scans of the chest are especially helpful for diagnosing this pattern of MAC lung disease, as bronchiectasis and small nodules may not be easily discernible on plain chest radiograph. The nodular/bronchiectasis radiographic pattern can also be seen with other NTM pathogens, including M. abscessus, Mycobacterium simiae, and M. kansasii. Solitary nodules and dense consolidation have also been described. Pleural effusions are uncommon, but reactive pleural thickening is frequently seen. Co-pathogens may be isolated from culture, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, and, occasionally, other NTM such as M. abscessus or Mycobacterium chelonae.19-21

Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis, initially described in patients who were exposed to hot tubs, mimics allergic hypersensitivity pneumonitis, with respiratory symptoms and culture/tissue identification of MAC or sometimes other NTM. It is unclear whether hypersensitivity pneumonitis is an inflammatory process, an infection, or both, and opinion regarding the need for specific antibiotic treatment is divided.11,22 However, avoidance of exposure is prudent and recommended.

Disseminated Disease

Disseminated NTM disease is associated with very low CD4+ lymphocyte counts and is seen in approximately 5% of patients with HIV infection.23-25 Although disseminated NTM disease is rarely seen in immunosuppressed patients without HIV infection, it has been reported in patients who have undergone renal or cardiac transplant, patients on long-term corticosteroid therapy, and those with leukemia or lymphoma. More than 90% of infections are caused by MAC; other potential pathogens include M. kansasii, M. chelonae, M. abscessus, and Mycobacterium haemophilum. Although seen less frequently since the advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy, disseminated infection can develop progressively from an apparently indolent or localized infection or a respiratory or gastrointestinal source. Signs and symptoms of disseminated infection (specifically MAC-associated disease) are nonspecific and include fever, night sweats, weight loss, and abdominal tenderness. Disseminated MAC disease occurs primarily in patients with more advanced HIV disease (CD4+ count typically < 50 cells/μL). Clinically, disseminated MAC manifests as intermittent or persistent fever, constitutional symptoms with organomegaly and organ-specific abnormalities (eg, anemia, neutropenia from bone marrow involvement, adenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly), and elevations of liver enzymes or lung infiltrates from pulmonary involvement.

Continue to: What are the criteria for diagnosing NTM pulmonary disease?