HIV: 3 cases that hid in plain sight

Having a high index of suspicion is key to recognizing the signs of HIV infection in patients without classic risk factors. How quickly would you have spotted these 3 cases?

The incidence of cytopenias in general correlates directly with the degree of immunosuppression. However, isolated hematologic abnormalities, including anemia and leukopenia, may be the initial presentation of HIV infection.9 As a result, HIV must be considered in the assessment of all patients who present with any hematologic abnormality.

Pneumocystis pneumonia. Pneumonia caused by the fungus Pneumocystis jirovecii has been a longtime AIDS-defining illness and is the most common opportunistic infection in patients with advanced HIV infection.10 A slow, indolent course is common, with symptoms of cough and dyspnea progressing over weeks to months (as observed in Mr. M). Radiographs will show diffuse or isolated ground-glass opacities. Partial improvement is sometimes seen in patients with unknown HIV infection who are treated with short courses of prednisone and antibiotics.11 Patients with untreated HIV infection and CD4+ T-cell counts <200 cells/mm3 will develop worsening hypoxemia and, in some cases, fulminant respiratory failure.

Herpes zoster is common in older adults and often indicates a weakened immune system. The incidence of zoster among adults with HIV is more than 15-fold higher than it is among age-matched varicella-zoster virus-infected immunocompetent people.12 A study from the early 1990s noted that nearly 30 cases per year were observed for every 1000 HIV-infected adults.12

Zoster tends to occur in patients with CD4+ counts >200 mm3. If HIV is not diagnosed when a patient presents with zoster, it may be several years before the CD4+ T-cell count declines to a level at which the patient will experience an opportunistic infection or malignancy. A diagnosis of herpes zoster should prompt you to consider HIV and test for infection, even in patients who do not have risk factors associated with HIV, as was the case with Ms. K.

Cryptococcal meningitis. Infections caused by Cryptococcus neoformans are now relatively infrequent in the United States but remain a major cause of AIDS-related morbidity and mortality in the developing world.13 Symptoms of cryptococcal meningitis, such as those observed in Mr. L, usually begin in an indolent fashion over one to 2 weeks. The most common presenting symptoms are fever, headache, and malaise. Nuchal rigidity, photophobia, and vomiting occur in only about 25% of patients.13 Mortality remains high for this infection if it is not treated aggressively.

Implement routine HIV screening, avoid “framing bias”

Prompt diagnosis of HIV infection is essential for several reasons. For one, it lowers the risk of life-threatening opportunistic infections and malignancies. For another, it can help to prevent transmission of HIV infection to partners and contacts.

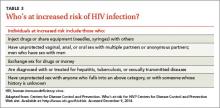

Historically, HIV testing had been considered primarily for individuals with certain high-risk factors that increase their likelihood of infection (TABLE 3). However, in 2006, recognizing that risk-based testing failed to identify a significant number of people with HIV, the CDC began to recommend opt-out routine HIV screening for all adolescents and adults ages 13 to 64 years.14 In November 2012, the US Preventive Services Task Force issued similar recommendations.15

In fact, routine screening would have likely led to earlier identification of HIV in 2 of the 3 patients in the cases described here. However, only 54% of US adults ages 18 to 64 years report ever having been tested for HIV, and among the 1.1 million people living with HIV/AIDS in the United States, approximately 15% do not know they are infected.16

Physicians are frequently subject to “framing bias” in which diagnostic capabilities are limited to how we perceive individual patients. Finn et al11 reported a case of a 65-year-old “grandfather” with COPD who was eventually diagnosed with Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia and subsequently found to be HIV-infected, with a CD4+ T-cell count of 5 cells/mm3. A similar case involving an 81-year-old patient was reported in the literature in 2009 and raised the question of whether patients older than the currently recommended age of 64 years should also undergo routine screening for HIV.17

The 3 patients described here illustrate a similar framing bias in that none of the physicians who cared for them in an outpatient setting considered their patient to be at risk for HIV infection.

To avoid this type of bias, we must remain vigilant in assessing risk factors for HIV infection while obtaining a patient’s medical history. However, even under ideal circumstances, our patients may not be forthcoming about their sexual behavior or drug use. Moreover, many others may be unaware that they were exposed to HIV. Consequently, FPs and other primary care providers should continue to incorporate routine HIV screening into their practices but also remember specific HIV risk factors and clinical indicators of disease.