How apps are changing family medicine

Medical applications for smartphones and tablets are so ubiquitous that it’s easy to become a victim of app overload. Here’s a look at FDA-approved apps, reference apps, and apps that FPs are “prescribing.”

“With a print textbook you have to cover up the answers so you don’t see them. Here, you don’t get to see the answer until you commit to one of the multiple choice answers. Then you get told what the correct answer is and why you got it right or wrong,” Dr. Usatine said. Interactivity, including the opportunity to watch a video, say, of a procedure to review how it’s done before embarking on it yourself, is a big part of the value of apps, he said.

Rx: App

In January, Eric Topol, MD, a prominent cardiologist and chief academic officer of Scripps Health in La Jolla, Calif., demonstrated the AliveCor heart monitor and other mobile devices on NBC’s Rock Center.8 In March, he went on The Colbert Report and examined Stephen Colbert’s ear with an otoscope smartphone accessory (CellScope) like the one used in Gaglani’s smartphone physical.9 Dr. Topol’s use of the mobile heart monitor to assess an airplane passenger in distress midflight also received widespread news coverage.

In response to an interviewer’s question, Dr. Topol said he is now more likely to prescribe an app than a drug.8 While it’s unlikely that any FP could make such a claim, many have begun recommending apps to tech-savvy patients.

Smartphones as symptom trackers

A January 2013 Pew Internet study found that 7 in 10 US adults track at least one health indicator, for themselves or a loved one. Six in 10 reported tracking weight, diet, or exercise, and one in 3 said they track indicators of medical problems, such as blood pressure, glucose levels, headaches, or sleep patterns—usually without the aid of a smartphone.10

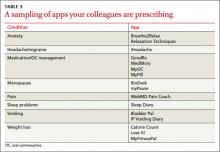

In fact, half of those who report tracking health measures said they keep the information “in their head,” and a third still use pencil and paper.10 That could change, of course, if their physicians suggest they do otherwise (TABLE 3).

Kelly M. Latimer, MD, an FP in the Navy stationed in Djibouti, Africa, routinely asks patients whether they have a smartphone and often recommends apps to those who do.

“It sounds like you have a lot of different symptoms,” she might say to a patient who complains of frequent headaches. “It will help me if you keep a headache diary.”

She used to give such patients paper and pen, Dr. Latimer noted. “Now I ask them to download the app (iHeadache, in this case) right then and there and do a quick review” so they’re ready to use it at home.

Apps are also a good way to help people with anxiety, Dr. Latimer has found. She frequently recommends apps like Relaxation Techniques and Breathe2Relax, and often suggests apps like Calorie Count and MyFitnessPal to boost patients’ efforts to lose weight and get in shape.

Abigail Lowther, MD, an FP at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, also recommends apps frequently. But she typically broaches the subject only with patients who have their smartphones out when she walks into the room.

Among the apps Dr. Lowther prescribes are myPause to track menopausal symptoms and Bladder Pal, a voiding diary for women struggling with incontinence. She advises women taking oral contraceptives to use the timer function on their phone to remember to take a pill at the same time every day. But there are apps (myPill, for one) that do that, too.

The upside of patient apps. A smartphone is ideal for keeping a symptom diary because it’s something that most people are never without. Anyone can use the notes function on a phone or tablet to jot down details about exacerbations, but those using disease-specific apps tend to capture more precise information. Some patients print out the information they’ve gathered and bring a hard copy to an office visit, while others simply show their physician what’s on their smartphone.

Can apps affect outcomes? There are few high-quality studies and the jury is still out, but “the smartphone has a very bright future in the world of medicine,” the authors of a review of smartphones in the medical arena concluded. After examining the use of apps to track (literally) wandering dementia patients; calculate and recommend insulin dosages for patients with type 1 diabetes; and teach yoga, to name a few, the researchers concluded that “the smartphone may one day be recognized as a diagnostic and therapeutic tool…as irreplaceable as the stethoscope.”11

Dr. Lowther recalls an obese patient who found MyFitnessPal to be helpful where other, more traditional diet programs had failed. The reason? He was less than truthful with the people overseeing the weight loss programs about what he’d eaten when he tried—and failed—to follow diets like Weight Watchers. He then ended up feeling so guilty that he abandoned the effort entirely. But, he told her, he “wouldn’t lie” to an app.