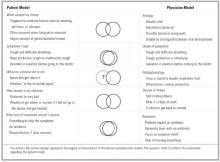

Patient and physician explanatory models for acute bronchitis

Physicians who did not feel pressure to prescribe antibiotics could be grouped into those who usually used antibiotics to treat acute bronchitis and those who took time to explain to their patients why they did not want to prescribe antibiotics. Some quotations that illustrate the views of this latter group were: “Usually I try to involve the patient in my thinking, until we feel some sort of consensus” and “I basically lay out why I’m not [prescribing an antibiotic].” A synopsis of the models is presented in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1

Discussion

It is well recognized in the literature that antibiotic usage in the therapy of acute bronchitis in the otherwise healthy adult (1) does not confer a clinically relevant shorter course of illness, (2) does not prevent the rare progression to pneumonia any better than placebo, (3) has a significantly negative impact on public health by contributing to antibiotic resistance, and thus (4) is not warranted.1-3,5,12,13 Nevertheless, antibiotic usage patterns have not changed significantly in the past 10 years, and antibiotics are still the traditional first-line therapy in practice. Reasons for this dichotomy are complex. The purpose of this qualitative study was to begin to clarify some of the complexities by determining incongruous areas of patient and physician beliefs regarding the diagnosis and management of acute bronchitis. Similarities and differences in 3 areas of patient and physician models warrant further discussion: etiology of acute bronchitis, course if untreated, and factors affecting the decision to treat.

Patients in this study had a vague understanding of the concept of infection and differences between bacteria and viruses. This finding has been reported in other patient-centered studies13-15 regarding respiratory infections and is likely due to inadequate or contradictory information imparted by the medical community through individual physician-specific communications and from the medical system as a whole. In contrast, physicians in the study uniformly noted a viral cause of most cases of bronchitis but often qualified the statements with concern of not knowing which individuals might have bacterial infections and the lack of tools to distinguish between viral and bacterial etiologies.

Further complicating this paradigm of conflict and confusion regarding viral and bacterial causes, patients consistently thought that not treating acute bronchitis with antibiotics would lead to prolonged, worsening, and potentially life-threatening illness. There is a lack of understanding among patients that acute bronchitis often results in a cough lasting longer than 2 weeks, and this may contribute to the misconception that prolonged duration of illness is evidence of more serious infection.

One cannot separate these 2 themes—confusion regarding etiology and miscommunication about the clinical course of untreated illness—from the decision to treat and the role of antibiotics. From the patients’ perspective, without antibiotics they would not get better. Compounding this belief is the patients’ urgent desire for symptom relief. Physicians reported significant internal conflict regarding treatment, characterized by a recognition that antibiotics were of little value, a universal assumption that patients expected antibiotics, a desire for patient satisfaction, perceived pressures from employers, and a fear of “missing” a more serious disease or making a mistake (from the desire to heal and the fear of medicolegal actions). These complex and conflicting perceptions, emotions, and cognitions are illustrated in Figure 2.

Over the past several decades, medical and lay traditions have evolved to imply that productive coughs with green-yellow sputum or colds with green-yellow nasal discharge represent bacterial infections or something that requires an antibiotic.4,5,16,17 Randomized clinical trials have not shown that treatment with antibiotics leads to significantly improved clinical outcomes.1-3,5 In a study of 1398 children, Vinson and Lutz reported that parental expectation of an antibiotic was second only to the presence of rales in increasing the likelihood of the diagnosis of bronchitis.18 With little in history or examination to distinguish between viral and bacterial infections and the fear of “missing something,” the presence or absence of yellow-green nasal secretions and sputum have become the “key” questions in our medical history. This has created a medical tradition that falsely implies to patients a different illness or outcome from those without secretion production or clear discharge. Is it any surprise that patients expect antibiotics?

In evaluating the generalizability of this study, potential biases and limitations of qualitative studies should be considered. First, the creation of this explanatory model was designed to generate ideas and hypotheses, not to test them. Second, the views represented were from a single medical specialty in one geographic area and based on physicians’ and patients’ subjective perceptions. Nevertheless, the goal of such a study was to provide a theoretical model of communication between patient and physician that generates questions for further exploration and areas for potential intervention.