Head off complications in late preterm infants

Late preterm infants may look like their full-term counterparts, but they face many more challenges. Here’s what to keep in mind.

Most experts agree that breastfeeding should be started in the delivery room, and plasma glucose checked at 60 minutes of life and any time an infant is symptomatic. A level less than 45 mg/dL during the transition period should prompt feeding.9 Glucose levels should be rechecked within an hour of feeding and every 3 hours thereafter. If the level remains low or the infant is not interested in feeding, give a bolus of D10W and consider an infusion.7,10 TABLE 110 highlights one proposed method of glucose management.

TABLE 1

How best to manage glucose in a late preterm newborn10

| Asymptomatic late preterm infants | Glucose level (mg/dL) | Response |

|---|---|---|

| Check plasma glucose at 1 hour of life | <45 | Feed, recheck 1 h |

| Subsequent glucose monitoring | <35 | IV infusion* |

| >35 | Rescreen q3h for 36 h | |

| Symptomatic late preterm infants | ||

| Infusion for goal >55 mg/dL | <45 | Minibolus;† IV infusion* |

| *IV infusion=D10W at 6-8 mg/kg/min. †Minibolus=200 mg/kg D10W (2 mL/kg). Adapted with permission from: Macmillan Publishers Ltd. Adamkin DH. Late preterm infants: severe hyperbilirubinemia and postnatal glucose homeostasis. J Perinatol. 2009;29:S12-S17. Copyright 2009. | ||

Respiratory distress

At least 30% of late preterm infants will have some evidence of respiratory distress,5 which is defined as the need for oxygen supplementation due to tachypnea, grunting, nasal flaring, retractions, or cyanosis. Those at highest risk are white males born via cesarean section.11 Transient tachypnea of the newborn (TTN) appears to be the cause of almost half the cases of respiratory distress in these young patients.12 As this is a diagnosis by exclusion, consider other common causes: respiratory distress syndrome, neonatal pneumonia, meconium aspiration syndrome, and persistent pulmonary hypertension.12 The need for ventilator support is a significant concern in this group and increases exponentially with decreasing gestational age.6

Hyperbilirubinemia

More than half of all late preterm infants will present with clinically significant jaundice.5 Late preterm infants have an increased bilirubin load, decreased uptake of bilirubin, and delayed conjugation. They are less able to bind bilirubin to albumin, which increases their predisposition to bilirubin-induced neurological dysfunction and kernicterus.13 They also have more difficulty with breastfeeding, which exacerbates their hyperbilirubinemia.14

Infants born at 36 weeks have an 8-fold increased risk of developing severe hyperbilirubinemia (total serum bilirubin >20 mg/dL) than those born at 41 weeks,13 which explains why they are disproportionately represented in the US Pilot Kernicterus Registry.14 These infants can develop neurological sequelae at lower levels of bilirubin than their term counterparts and have less chance of complete recovery once intensive therapy has been implemented.14

The 2 main risk factors for severe hyperbilirubinemia have to do with discharge time and breastfeeding. Discharge at less than 48 hours is a risk factor for both term and late preterm infants.14,15 This is likely due to the fact that bilirubin peaks in late preterm infants between Days 5 and 7, and in term infants between Days 3 and 5.16 Difficulties with breastfeeding, the second risk factor,17 can be due to a combination of delayed maternal lactogenesis and ineffective milk removal on the part of the infant.18 When infants ingest smaller volumes of milk, bowel movements are infrequent and the bilirubin in the gut gets reabsorbed instead of excreted.

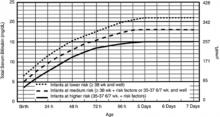

American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) guidelines suggest measuring total serum bilirubin or transcutaneous bilirubin and plotting the value on an hour-specific, gestational-age-specific, risk-specific nomogram (FIGURE).19 Alternately, BiliTool (https://www.bilitool.org) can be used to individualize an infant’s risk.

FIGURE

Bilirubin levels and risk of significant hyperbilirubinemia19

Bilirubin levels should be plotted according to the infant’s hours of life and assessed according to risk factors on the appropriate risk line. If infants are 34 weeks 0 days to 34 weeks 6 days, they should be assessed on the high risk line.

- Use total bilirubin. Do not subtract direct reacting or conjugated bilirubin.

- Risk factors include isoimmune hemolytic disease, G6PD deficiency, asphyxia, significant lethargy, temperature instability, sepsis, acidosis, or albumin <3.0 g/dL (if measured).

- For well infants 35-37 6/7 weeks, you can adjust the total serum bilirubin (TSB) levels for intervention around the medium risk line. It is an option to intervene at lower TSB levels for infants closer to 35 weeks and at higher TSB levels for those closer to 37 6/7 weeks.

- It is an option to provide conventional phototherapy in the hospital or at home at TSB levels of 2-3 mg/dL (35-50 mmol/L) below those shown, but home phototherapy should not be used in any infant with risk factors.