Does oral creatine supplementation improve strength? A meta-analysis

- OBJECTIVES: Oral creatine is the most widely used nutritional supplement among athletes. Our purpose was to investigate whether creatine supplementation increases maximal strength and power in healthy adults.

- STUDY DESIGN: Meta-analysis of existing literature.

- DATA SOURCES: We searched MEDLINE (1966–2000) and the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register (through June 2001) to locate relevant articles. We reviewed conference proceedings and bibliographies of identified studies. An expert in the field was contacted for sources of unpublished data. Randomized or matched placebo controlled trials comparing creatine supplementation with placebo in healthy adults were considered.

- OUTCOMES MEASURED: Presupplementation and postsupplementation change in maximal weight lifted, cycle ergometry sprint peak power, and isokinetic dynamometer peak torque were measured.

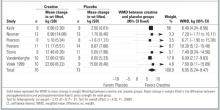

- RESULTS: Sixteen studies were identified for inclusion. The summary difference in maximum weight lifted was 6.85 kg ( 95% confidence interval [CI], 5.24–8.47) greater after creatine than placebo for bench press and 9.76 kg (95% CI, 3.37–16.15) greater for squats; there was no difference for arm curls. In 7 of 10 studies evaluating maximal weight lifted, subjects were young men (younger than 36 years) engaged in resistance training. There was no difference in cycle ergometer or isokinetic dynamometer performance.

- CONCLUSIONS: Oral creatine supplementation combined with resistance training increases maximal weight lifted in young men. There is no evidence for improved performance in older individuals or women or for other types of strength and power exercises. Also, the safety of creatine remains unproven. Therefore, until these issues are addressed, its use cannot be universally recommended.

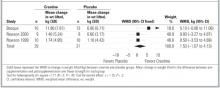

There was no significant difference in 1-repetition maximum arm flexor strength with creatine supplementation (WMD = 1.53 kg; 95% CI, –1.07 to 4.13; n = 60; Figure 2). However, 2 trials20,21 of the 3 evaluating this outcome studied subjects older than 60 years and did not employ adjuvant weight training programs. The study that incorporated resistance training and evaluated younger subjects22 found a modest (29.9% vs 16.5%) improvement in 1-repetition maximum arm flexor strength with creatine compared with placebo.

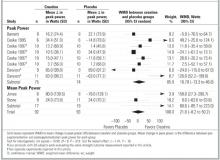

For 1-repetition maximum squat, creatine supplementation resulted in a strength increase of 9.76 kg (95% CI, 3.37–16.15; n = 74) greater than that of placebo (Figure 3). There was no advantage to longer-term supplementation (10.9 kg more than placebo [95% CI, 3.4–18.4] for 5–6 weeks compared with 10.4 kg [95% CI, 3.5–17.2] for 10–12 weeks). Again, in all but 1 study17 measuring squat performance, subjects were previously trained young men engaging in adjuvant resistance training programs, so subanalysis for other variables was not possible. For previously sedentary women, Vandenberghe et al17 found no difference at 5 weeks, but they did find a significant improvement in 1-repetition maximum squat performance with creatine supplementation at 10 weeks. Tests for heterogeneity were nonsignificant for all absolute strength variables.

To evaluate for publication bias, we examined funnel plots of each of the 3 absolute strength outcomes (bench press, arm flexor, and squat exercises). No evidence of publication bias was demonstrated. Figure W1 (available on the JFP Web site: https://www.jfponline.com) depicts a composite funnel plot of all 3 outcomes using a standardized mean difference to allow comparison between these 3 different outcomes.

FIGURE 1 Studies assessing 1- to 3-repetition maximum bench press strength

FIGURE 2 Studies assessing 1-repetition maximum arm flexor strength

FIGURE 3 Studies assessing 1-repetition maximum squat strength

Cycle ergometer peak power

Creatine supplementation had no effect on peak power production during cycle ergometry sprint (Figure 4). Results among studies were widely variable (test for heterogeneity P= .035), so a random effects model was used to pool data. The summary weighted mean difference of 16.79 W (95% CI, –13.26 to 46.84; n = 149) was insignificant, both statistically (test for overall effect P= .3) and clinically, because this represents approximately a 1% change greater than baseline. Two studies23,24 looked at mean peak power across a series of 15-to 30-second sprints and found inconsistent results, with a summary weighted mean difference of 68.61 W (95% CI, –85.74 to 222.97; n = 36). Of note, for the 2 studies24,25 that demonstrated improved performance with creatine, the difference was accentuated by an unexplained but pronounced worsening of performance after supplementation in the placebo groups.

FIGURE 4 Studies assessing cycle ergometer sprint peak power

Dynamometer peak torque

Only 3 studies21,26,27 evaluated peak torque, and all used slightly different outcome assessments. One study26 reported average peak torque across 30 isokinetic leg flexion/extension contractions; 1 study21 reported the sum of peak torque across 5 sets of 30 isokinetic leg flexion/extension contractions; and 1 study27 gave peak torque data for isokinetic leg extension but did not describe precisely how peak torque was determined. There was no difference between creatine and placebo for isokinetic leg flexion/extension peak torque using a standardized mean difference to account for variations in measurement of this outcome. Tests for heterogeneity were nonsignificant for this outcome (P= .19).

Adverse effects

Four studies commented on short-term adverse effects of creatine supplementation. Three studies17,23,28 found no difference between creatine and placebo. One study21 reported gastrointestinal upset, rash, or headache in 3 subjects taking creatine and no adverse effects in subjects taking placebo. None of these studies was designed to evaluate long-term adverse effects of creatine supplementation, and there were no reports of longer-term follow up.

Discussion

This is the first study to report quantitatively the effect of creatine supplementation on strength performance from meta-analysis of the existing literature. We found that oral creatine supplementation improves maximal resistance exercise performance in previously trained young men. There is insufficient evidence that creatine improves other measures of strength, such as cycle ergometry sprint peak power or isokinetic dynamometer peak torque, or that creatine improves strength in women or older individuals. The effect of creatine on endurance, submaximal exercise, or actual “on-field” athletic performance was not addressed.

Creatine’s ergogenic properties may result from allowing increased work during training and decreasing recovery time. If so, creatine must be combined with adjuvant training to increase strength and power. Only studies investigating maximal weight-lifting performance incorporated resistance-training programs specific to the outcome being measured. Three studies included weight training but investigated non–weight-lifting outcomes,23,24,27 and only 1 study24 found a benefit from creatine supplementation. It is unclear whether the lack of effect for non–weight-lifting outcomes means that creatine is not beneficial unless combined with specific adjuvant training or that creatine simply is not ergogenic for outcomes other than maximal weight lifted.