Aspirin prophylaxis in patients at low risk for cardiovascular disease: A systematic review of all-cause mortality

- OBJECTIVE: We investigated whether aspirin reduces all-cause mortality in low-risk patients.

- STUDY DESIGN: We systematically reviewed studies of aspirin for primary prevention to measure total mortality. We included all clinical trials, cohort studies, and case control studies that assessed primary prevention, included low-risk subjects, and measured total mortality. The quality of studies was evaluated with a standard scale.

- DATA SOURCES: MEDLINE, the Cochrane Library, and the Internet were systematically searched for studies with the key terms primary, prevention, aspirin, myocardial infarction, stroke, and mortality. Reference lists of identified trials and reviews also were examined.

- POPULATION: Active members in the Indiana Academy of Family Physicians 2000–2001 membership database (N = 1328).

- OUTCOMES MEASURED: Primary outcomes were myocardial infarction, stroke, and mortality.

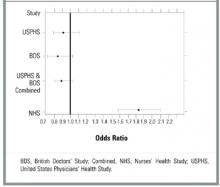

- RESULTS: Three primary prevention studies met our criteria. Two clinical trials, the United States Physicians Health Study and British Doctors Study, demonstrated no significant decrease in mortality in the aspirin group alone or when results from the 2 studies were combined. The United States Physicians Health Study showed a lower rate of myocardial infarction (odds ratio [OR], 0.58; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.47–0.71). In the Nurses Health Study, a cohort study, taking aspirin at any dose was associated with higher rates of myocardial infarction (OR, 2.34; CI, 1.92–2.86), stroke (OR, 1.84; CI, 1.39–2.44), and all-cause mortality (OR, 1.83; CI, 1.57–2.14).

- CONCLUSIONS: There is currently no evidence to recommend for or against the use of aspirin to decrease mortality in low-risk individuals.

In the British Doctors Study (BDS), 66% of patients were randomized to take aspirin once daily and 33% were to avoid aspirin.21 More than half of the subjects were at least 60 years old. Physicians with stroke, myocardial infarction, ulcer disease, or currently taking any aspirin products were excluded. Six percent of the subjects had a history of heart disease other than myocardial infarction, 10% had hypertension, and 75% of participants were currently smoking or had a history of smoking. No significant differences were noted between groups for myocardial infarction or total mortality. By the end of the study, 44% of the aspirin group had discontinued aspirin secondary to side effects, the most common being dyspepsia. Of the control group, 2% per year started using aspirin because they developed risk factors such as vascular disease or for primary prevention. Low-risk individuals were not evaluated separately.

The Nurses Health Study (NHS) was a cohort study of women who were free of diagnosed coronary heart disease, stroke, and cancer at the start of the study. However, 29% of the women smoked and 15% had hypertension.22 The mean age was 46.0 years, and the follow-up was 96.7% of total potential person years. The study respondents were asked how many aspirin tablets they took per week: 0, 1 to 3, 4 to 6, 7 to 14, or 15+. Those who smoked or were overweight were more likely to take aspirin. No separate analysis of low-risk subjects was performed. Mortality from aspirin use was clearly dose dependent. For study participants taking 1 to 6 aspirin tablets each week, mortality was 0.84% (OR, 1.51; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.26–1.82); for those taking 7 to 14 aspirin tablets, mortality was 0.99% (OR, 1.80; CI, 1.39–2.33); and for those taking 15+ aspirin tablets, mortality was 1.82% (OR, 3.32; CI, 2.62–4.21). Rates of myocardial infarction and stroke also were higher for all groups taking aspirin (see Table 2). When combined, the USPHS and the BDS demonstrated no significant difference in mortality between aspirin and placebo groups, whereas the NHS found increased mortality from aspirin (Figure).

TABLE 1

Characteristics of aspirin studies that included low-risk subjects

| USPHS | BDS | NHS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trial | Steering Committee20 | Peto et al21 | Manson et al22 |

| Study population | Healthy US physicians | Healthy UK physicians | Healthy US nurses |

| Study type | Randomized controlled trial | Randomized controlled trial | Cohort |

| Subjects in aspirin group | 11,037 | 3429 | 35,048 |

| Subjects in control group | 11,034 | 1710 | 52,630 |

| Treatment | 325 mg aspirin every other day | 500 mg/d aspirin | 1–15 aspirin tablets/wk |

| Comparison | Placebo | No aspirin | None |

| Follow-up time (y) | 5 | 6 | 6 |

| Jadad score | |||

| Randomization† | 1 | 2 | NA* |

| Blinding ‡ | 1 | 0 | NA |

| Withdrawals § | 1 | 0 | NA |

| Total | 3 | 2 | NA |

| Significant difference in mortality | No | No | Yes in favor of no aspirin |

| *The Jadad scale does not apply to cohort studies. | |||

| †Two points maximum. | |||

| ‡Two points maximum. | |||

| §One point maximum. | |||

| BDS, British Doctors Study; NA, not applicable; NHS, Nurses Health Study; USPHS, US Physicians Health Study. | |||

TABLE 2

Rates of myocardial infarction, stroke, total cardiovascular mortality, and total mortality in studies of aspirin vs no aspirin that included low-risk patients

| Study | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | USPHS (5 y) | BDS (6 y) | NHS (6 y) |

| Myocardial infarction | |||

| Aspirin, n (%) | 139 (1.26) | 169 (4.93) | 244 (0.70) |

| No aspirin, n (%) | 239 (2.17) | 88 (5.15) | 157 (0.30) |

| OR (CI) | 0.58 (0.47–0.71) | 0.96 (0.73–1.24) | 2.34 (1.92–2.86)* |

| Stroke | |||

| Aspirin, n (%) | 119 (1.08) | 91 (2.65) | 109 (0.31) |

| No aspirin, n (%) | 98 (0.89) | 39 (2.28) | 89 (0.17) |

| OR (CI) | 1.22 (0.93–1.59) | 1.17 (0.80–1.71) | 1.84 (1.39–2.44)* |

| Total cardiovascular mortality | |||

| Aspirin, n (%) | 81 (0.73) | 148 (4.32) | 68 (0.19) |

| No aspirin, n (%) | 83 (0.75) | 79 (4.62) | 62 (0.12) |

| OR (CI) | 0.98 (0.72–1.33) | 0.93 (0.70–1.23) | 1.65 (1.17–2.33)* |

| Total mortality | |||

| Aspirin, n (%) | 217 (1.97) | 270 (7.87) | 354 (1.01) |

| No aspirin, n (%) | 227 (2.06) | 151 (8.83) | 292 (0.55) |

| OR (CI) | 0.95 (0.79–1.15) | 0.88 (0.72–1.09) | 1.83 (1.57–2.14)* |

| *OR significant at the .05 level. | |||

| BDS, British Doctors Study; CI, 95% confidence interval; n (%), number (percentage) of patients taking or not taking aspirin; NHS, Nurses Health Study; OR, odds ratio; USPHS, US Physicians Health Study. | |||

FIGURE Forest plot of mortality in healthy patients on aspirin

Discussion

To date, there has been no study of aspirin for primary prevention that included a separate analysis of patients who were free of cardiovascular risk factors. Each of the 3 studies that included low-risk subjects grouped them with subjects at higher risk, those known to benefit from aspirin.9,11,12 Even so, none of those studies demonstrated a statistically significant decrease in all-cause mortality. Even when combined, the BDS and the USPHS demonstrated no significant improvement in mortality. Mortality in the BDS was nearly 4 times greater than that in the USPHS. This finding is likely due to the higher baseline rate of smoking and other risk factors in the British doctors. In contrast to the BDS, the USPHS demonstrated significantly decreased rates for fatal and nonfatal myocardial infarction. Our analysis of the NHS associated aspirin with increased mortality, fatal myocardial infarction, and nonfatal myocardial infarction at any dose. The nurses on average had lower risk than the doctors, fewer smoked, and they were younger.

Many studies have clearly demonstrated the benefits of aspirin for primary prevention in high-risk subjects.10-12,25 There may be other benefits to taking prophylactic aspirin. In the Cancer Prevention Study II, aspirin use was associated with decreased death rates from colon cancer.26 Unfortunately, that study did not measure all-cause mortality.