COPD inhaler therapy: A path to success

Keys to therapeutic success include choosing the right device and drug regimen, providing rigorous patient education, and reducing environmental exposures.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Follow guideline advice that (1) in general, short-acting beta-agonists (SABAs) are not for daily use in stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) but (2) agents in this class of drugs might have a role in relieving occasional COPD-associated dyspnea. C

› Prescribe albuterol over levalbuterol when a SABA is indicated because of the lower cost of albuterol, its comparative efficacy, and its lower incidence of tachycardia and palpitations, even in patients with cardiovascular disease. B

› Avoid the use of an inhaled corticosteroid, or consider withdrawing inhaled corticosteroid therapy, in patients with COPD whose blood eosinophil count is < 100 cells/μL or who have repeated bouts of pneumonia or a history of mycobacterial infection. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Exposure to air pollution. Air pollutants other than tobacco smoke remain important modifiable factors that impact COPD. These include organic and inorganic dusts, chemical agents and fumes, and burning of solid biomass (eg, wood, coal) indoors in open fires or poorly functioning stoves.1 With this risk in mind, counsel patients regarding efficient home ventilation, use of nonpolluting cooking stoves, and the reduction of occupational exposure to these potential irritants.

GOLD approach to starting and adjusting inhaled therapy

Initiating inhaled therapy

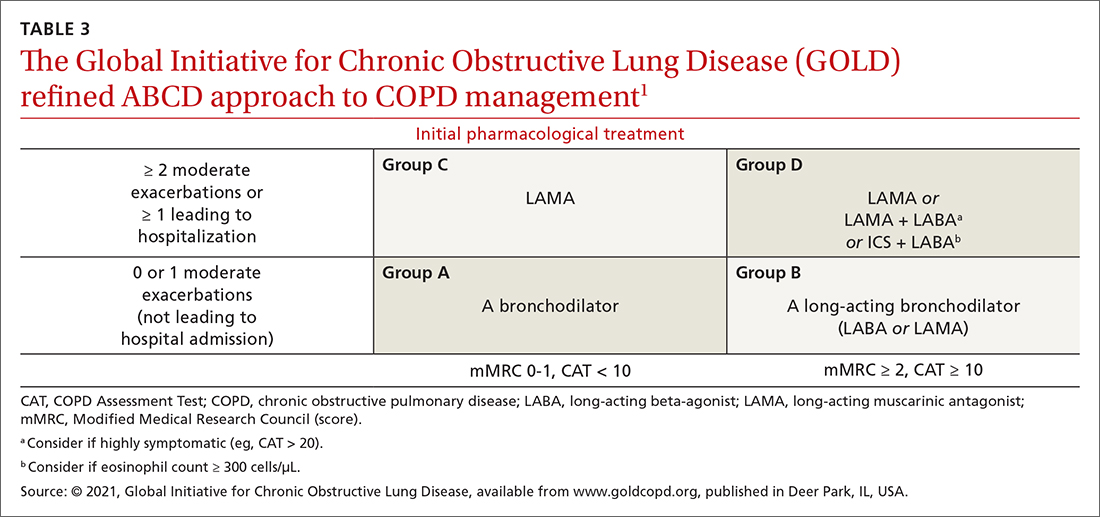

A good resource for family physicians is the GOLD refined ABCD assessment scheme for initiating inhaler therapy that integrates symptoms and exacerbations (TABLE 31). To assess the severity of dyspnea, either the Modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) Questionnaire or COPD Assessment Test (CAT) can be used. A moderate exacerbation requires an oral corticosteroid or antibiotic, or both; a severe exacerbation requires an emergency department visit or hospitalization, or both. TABLE 31 offers a guide to choosing initial therapy based on these factors.1

Following up on and adjusting an inhaler regimen

Adjust inhaler pharmacotherapy based on whether exacerbations or daily symptoms of dyspnea are more bothersome to the patient. Escalation of therapy involves adding other long-acting agents and is warranted for patients with exacerbations or severe or worsening dyspnea. Before escalating therapy with additional agents, reassess the appropriateness of the delivery device that the patient has been using and assess their adherence to the prescribed regimen.1

Dyspnea predominates. Escalate with LABA + LAMA. For a patient already taking an ICS, consider removing that ICS if the original indication was inappropriate, no response to treatment has been noted, or pneumonia develops.1

Exacerbations predominate. Escalate with LABA + LAMA or with LABA + ICS. Consider adding an ICS in patients who have a history of asthma, eosinophilia > 300 cells/uL, or eosinophilia > 100 cells/uL and 2 moderate exacerbations or 1 severe (ie, hospitalizing) exacerbation. This addition of an ICS results in dual or triple therapy (ie, either LABA + ICS or LABA + LAMA + ICS).1

Continue to: Unclear what predominates?