Scabies: Refine your exam, avoid these diagnostic pitfalls

Nearly half of all infections are missed when first examined. Attentiveness to specific details, particularly in 3 common scenarios, can help ensure an accurate Dx.

VIDEO shows scabies mite in motion

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Consider scabies with any severe pruritic eruption. Conduct a thorough physical exam, preferably with a dermatoscope, for burrows in the webs and sides of fingers, proximal palm, and wrists. A

› Consider scabies in all patients—especially the immunocompromised—who have distal white or yellow thick, scaly, or crusted plaques. C

› Include scabies in the differential when patients present with smooth nodules of the genitals or pruritic smooth papules and plaques in other locations. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

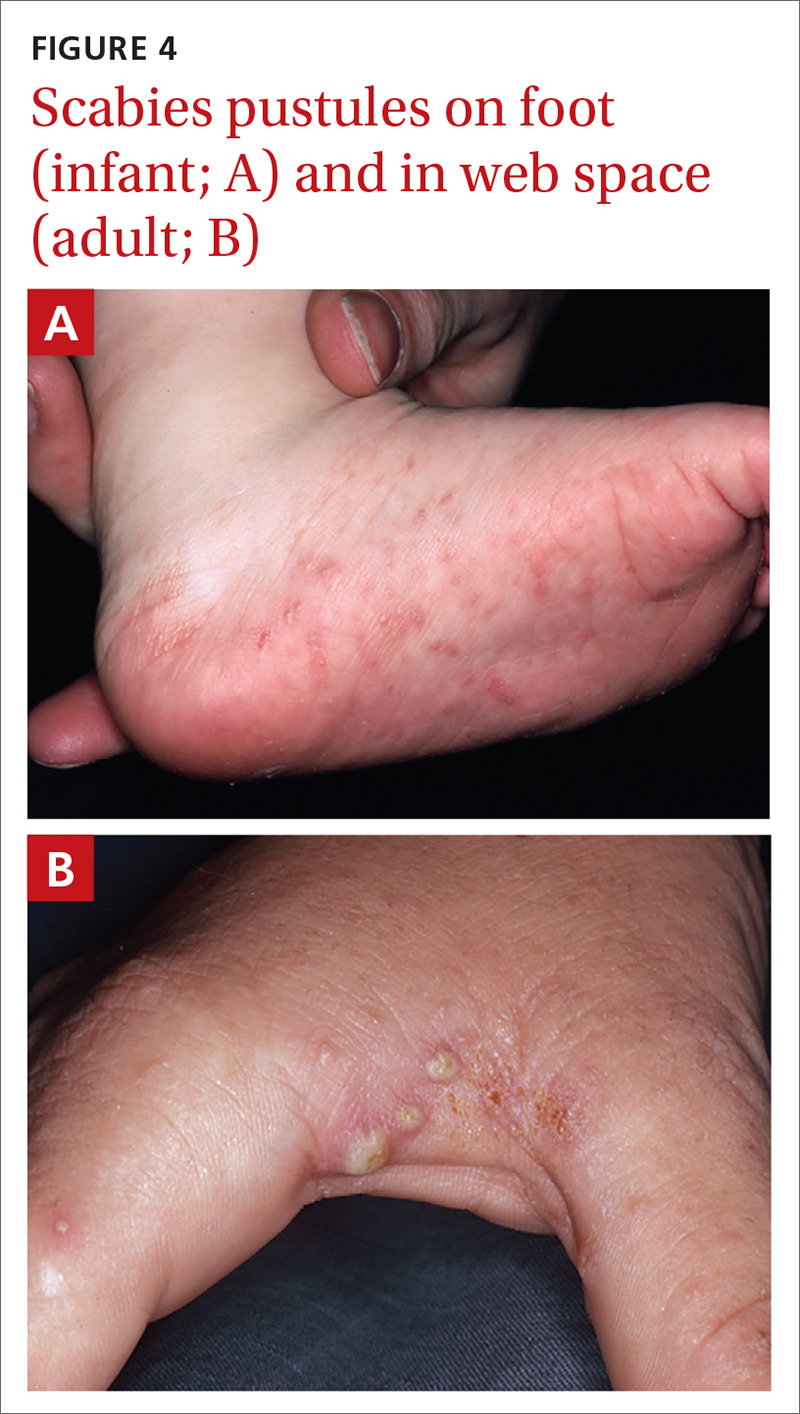

Pustular scabies is commonly seen in children and adolescents but can occur in all age groups. Patients may present with vesicular pustular lesions (FIGURE 4A and 4B).7 In some cases, topical corticosteroids have modified the classic clinical presentation into a pustular variant. However, scabies alone can cause pustular lesions.

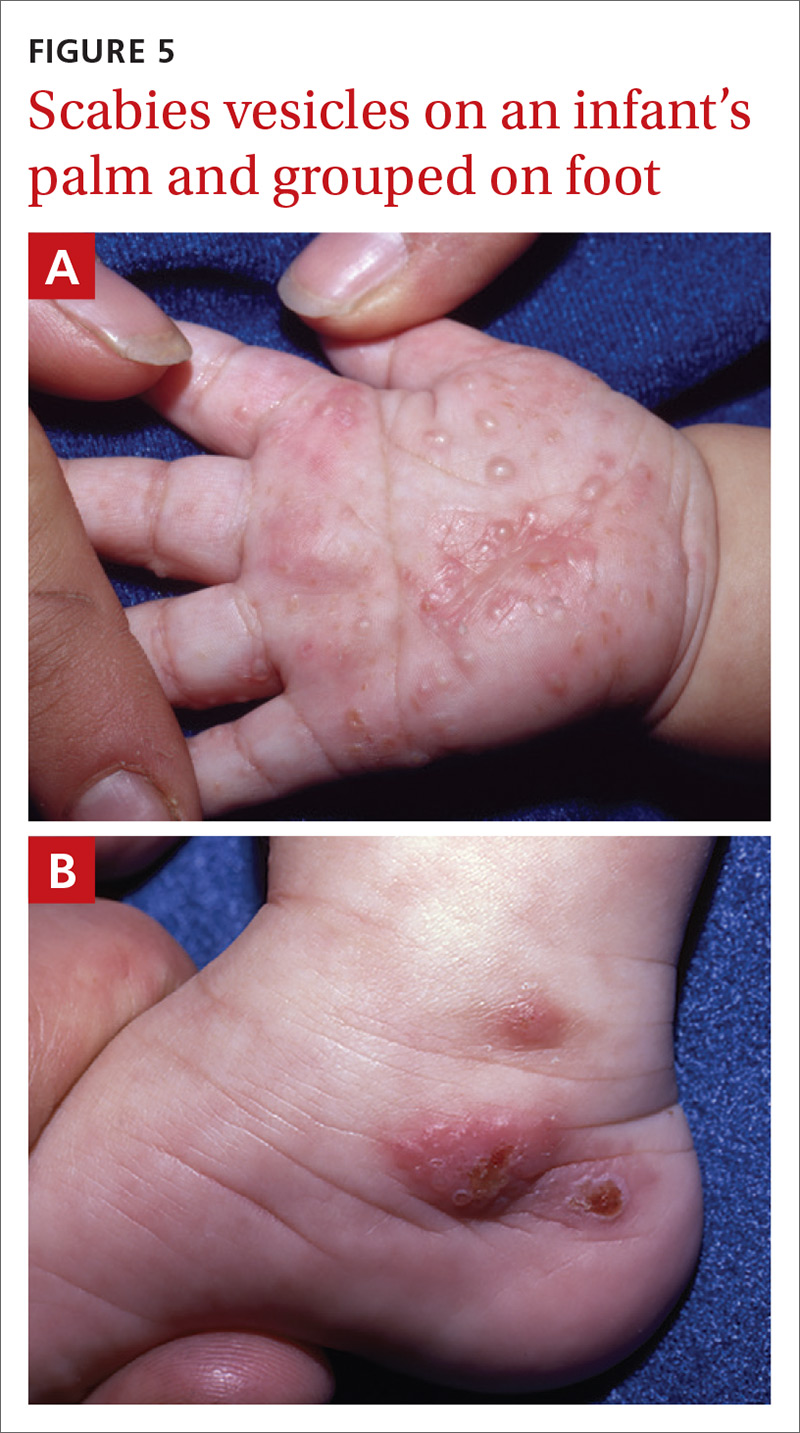

Vesiculobullous scabies (FIGURE 5A and 5B) is a clinical subtype that may be mistaken for pemphigus vulgaris9 or bullous pemphigoid10 because of its strikingly similar clinical presentation to those disorders.

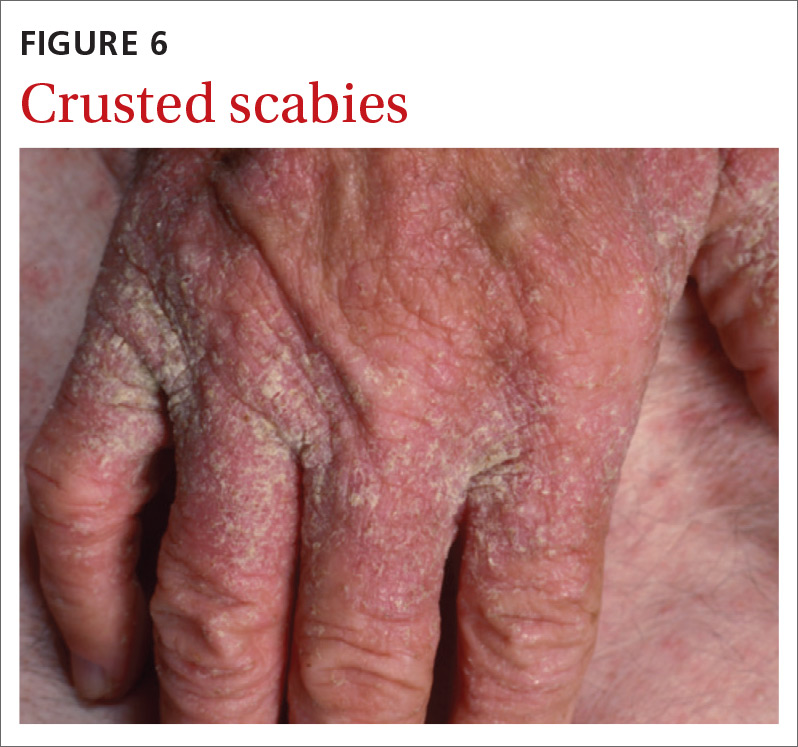

Crusted scabies (Norwegian scabies) is a severe, disseminated form of scabies that commonly affects immunocompromised patients, although cases are also seen in immunocompetent hosts. Afflicted immunocompetent patients often have a history of diabetes mellitus, liver cirrhosis, malnutrition, or alcohol abuse.11 Patients present with a thick powdery or crusted white or yellow scale involving the feet or hands (FIGURE 6) that sometimes extends onto the limbs. Severe cases can involve wide body surfaces. One unusual presentation also included a desquamating rash without pruritus.12

Highly atypical cases

Atypical presentations include lesions that appear outside of the classic distribution areas of scabies, lesions with uncharacteristic morphology, cases with coinfections, and instances in which patients are immunocompromised.13 Examples include scabies of the scalp coexisting with seborrheic dermatitis or dermatomyositis,14 scabies mimicking mastocytoma,15,16 and scabies with coinfections of impetigo or eczema.17 These coinfections and clinical variations can be particularly challenging. Other reports of atypical scabies leading to misdiagnosis include a case of crusted scabies mimicking erythrodermic psoriasis18 and a case initially attributed to suppurative folliculitis and prurigo nodularis.19

Decisive diagnostic measures

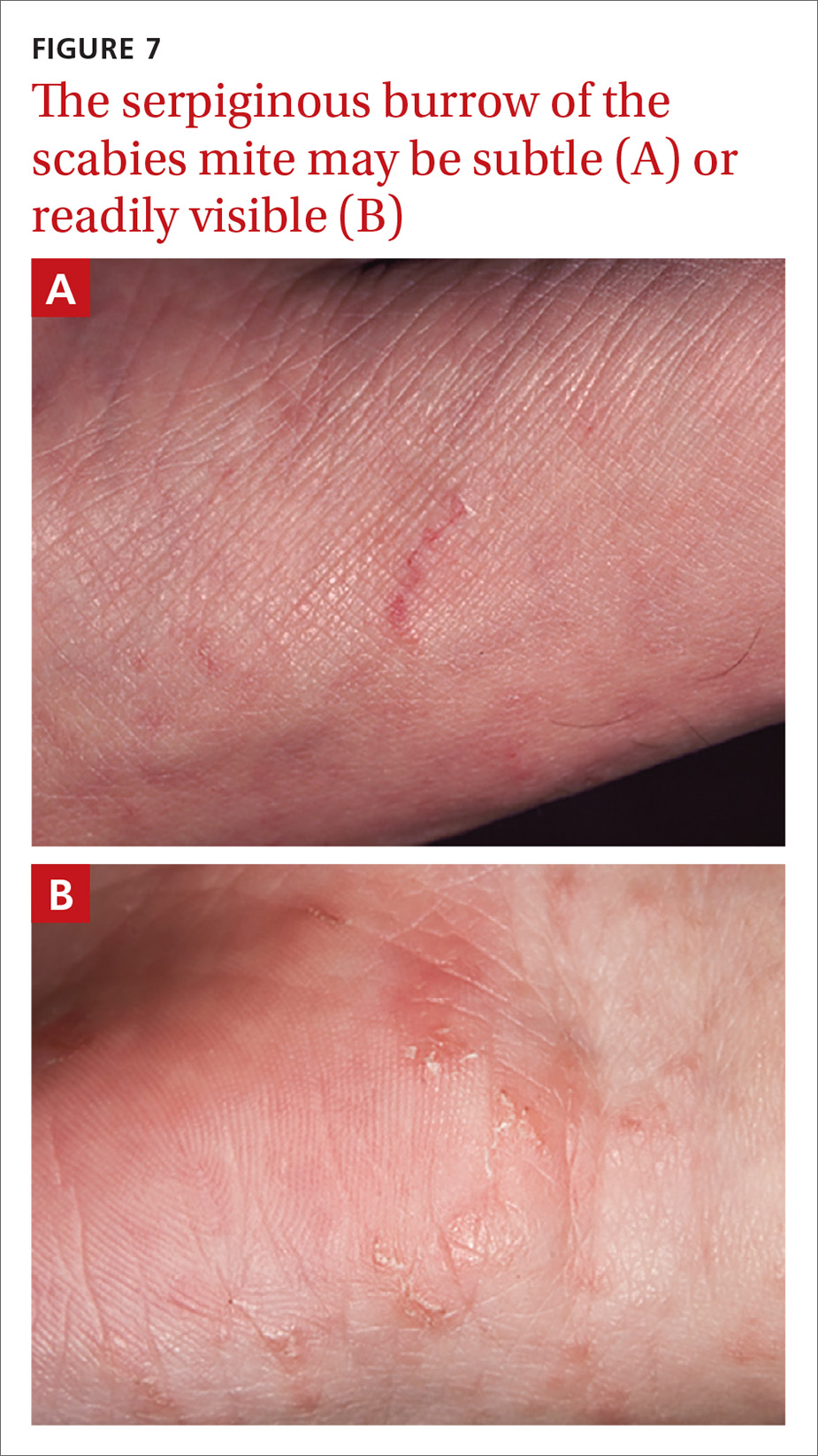

Identifying the mite’s burrow on clinical exam is essential to making the diagnosis of scabies. Microscopic examinations of burrow scrapings remain the diagnostic gold standard. Frequently, nondermatologists perform skin scrapings of the pruritic papules of scabies instead of the burrows. These papules are a hypersensitivity reaction to the mites, and no scabetic mites will be found there. Burrows appear on exam as small, linear, serpiginous lines (FIGURE 7A and 7B).

Continue to: Handheld illumination with a dermatoscope...