What family physicians can do to combat bullying

Bullying has significant health implications for young people and society at large. These screening tools, tips for responding to bullies, and Web resources can help.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Suspect bullying when children with chronic conditions that were stable begin deteriorating for unexplained reasons or when children become non-adherent to medication regimens. C

› Empower not only patients, but also parents/caregivers, to take action and deter bullying behaviors. B

› Support school-based and community-oriented intervention programs, which have been shown to be among the most effective strategies for curbing bullying. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Screening: Best practices

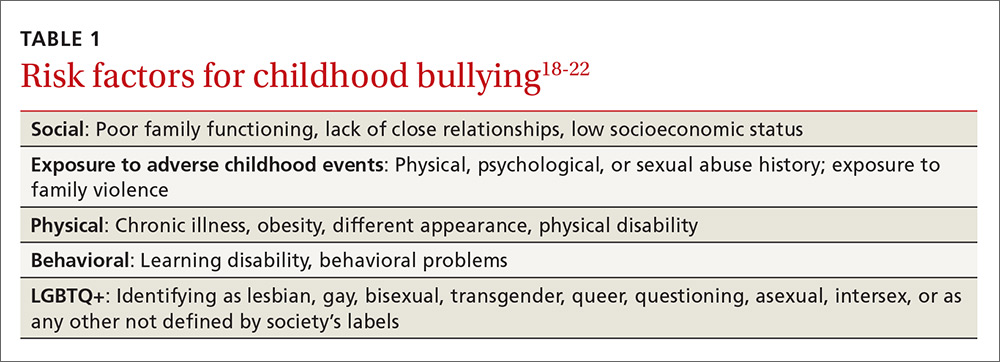

The FP’s role begins with screening children at risk for bullying (TABLE 118-22) or those whose complaints suggest that they may be victims of bullying.

Start screening when children enter elementary school

Given that providers’ time is limited for every patient visit, it is important to address bullying at times that are most likely to yield impactful results. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that the topic of bullying be introduced at the 6-year-old well-child visit (a typical age for entry to elementary school).7 Views in the literature are inconsistent regarding when and how to address bullying at other time points. One approach is to pre-screen those with risk factors associated with bullying (TABLE 118-22), and to focus screening on those with warning signs of bullying, which include mood disorders, psychosomatic or behavioral symptoms, substance abuse, self-harm behaviors, suicidal ideation or a suicide attempt, a decline in academic performance, and reports of school truancy. Parental concerns, such as when a child suddenly needs more money for lunch, is having aggressive outbursts, or is exhibiting unexplained physical injuries, should also be regarded as cues to screen.9

Screen patients in high-risk groups

A number of groups of children are at high risk for bullying and warrant targeted screening efforts.

- Children with special health needs. Research has shown that children with special health needs are at increased risk for being bullied.18 In fact, the presence of a chronic disease may increase the risk for bullying, and bullying often negatively impacts chronic disease management. As a result, it’s important to have a high index of suspicion with patients who have a chronic disease and who are not responding as expected to medical management or who experience deterioration after being previously well-controlled.18

- Children who are under- or overweight. Similarly, bullying based on a child's weight is a phenomenon that has been recognized to have a significant impact on children’s emotional health.19

- Youth who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer/questioning (LGBTQ+) are more likely than non-LGBTQ+ peers to attempt suicide when exposed to a hostile social environment, such as that created by bullying.20

Screening need not be complicated

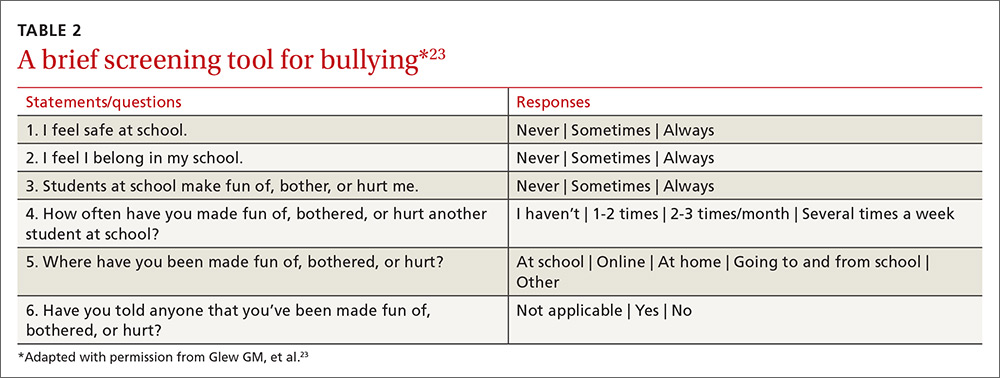

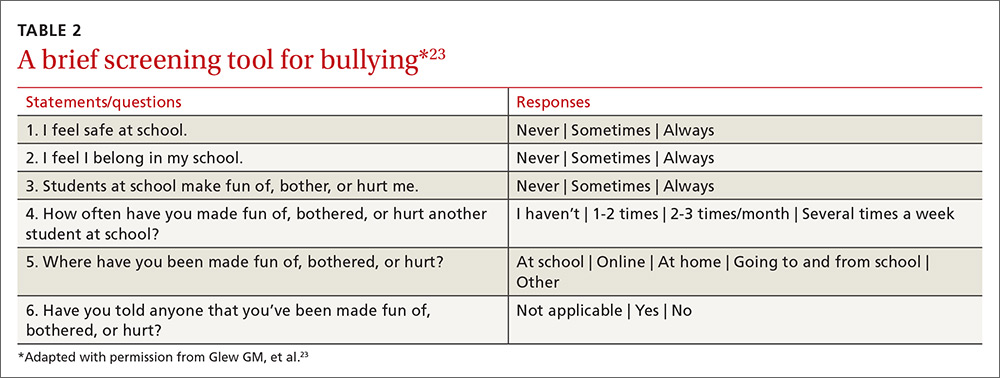

One screening approach is simply to ask patients, “Are you being bullied?” followed by such questions as, “How often are you bullied?” or “How long have you been bullied?” Asking about the setting of the bullying (Does it happen at school? Traveling to/from school? Online?) and other details may help guide interventions and the provision of resources.9 Another approach is to provide patients with some type of written survey (see TABLE 223 for an example) to encourage responses that patients might be reluctant to disclose verbally.23,24 (See “Barriers to screening.")

SIDEBAR

Barriers to screeningScreening for any condition presupposes a response. Ideally, family physicians should be prepared to provide basic counseling, resources, and, if necessary, treatment, if a patient screens positive for bullying. But screening for violence or bullying can be difficult, and evidence-based guidelines for screening and intervention are lacking, leaving many primary care practitioners feeling ill-equipped to meaningfully respond.

One study of the use of a screening tool aimed at intimate partner violence (IPV) showed that even with the availability of a screening tool, health care providers’ use of the tool was inconsistent and referral practices were ineffective.1 Providers cited the following limiting factors in screening for IPV: 1) a lack of immediate referral availability, 2) a lack of time during the office visit, and 3) a lack of confidence in the ability to screen.1 These same issues may be barriers to screening for bullying.

1. Ramachandran DV, Covarrubias L, Watson C, et al. How you screen is as important as whether you screen: a qualitative analysis of violence screening practices in reproductive health clinics. J Community Health. 2013;38:856-863.

Provider and parental interventions

Interventions often entail counseling the patient and the family about bullying and its effects, empowering victims and their caregivers, and screening for bullying comorbidities and correlates.2 Refer patients to behavioral health specialists when there is evidence of pervasive effects on mood, behavior, or social development, but keep in mind that counseling can begin in your own exam room.

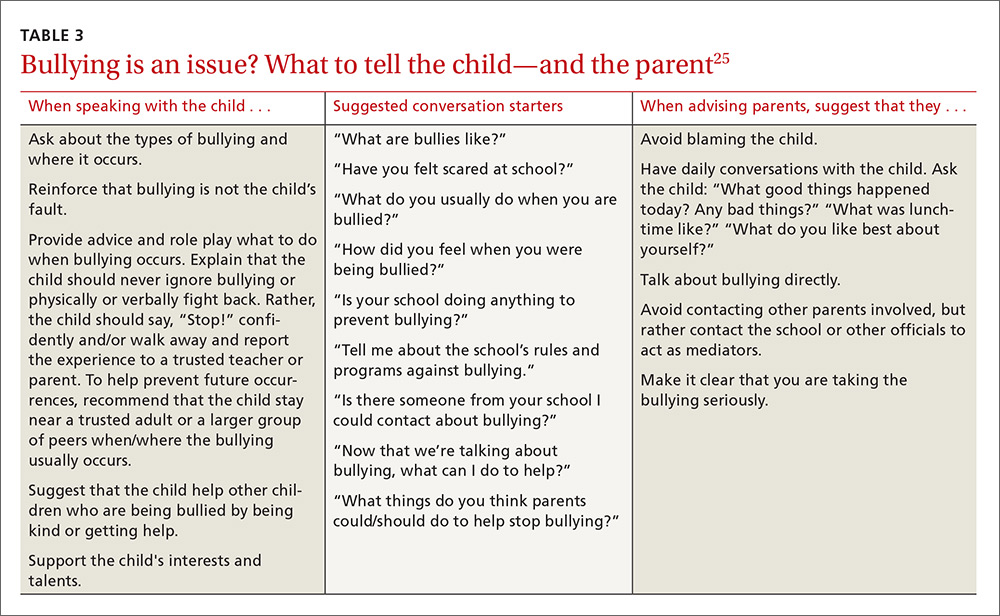

Effective discussion starters. Affirming the problem and its unacceptability, talking about the different types of bullying and where bullying may occur, and asking about patient perceptions of bullying can be effective discussion starters. FPs should help patients identify bullying, open lines of communication between children and their parents and between parents and other caregivers, and demonstrate respect and kindness in their approach to discussing the topic. Encourage children to speak with trusted adults when exposed to bullying. Talk to them about standing up to bullies (saying “stop” confidently or walking away from difficult situations) and staying safe by staying near adults or groups of peers when bullies are present (TABLE 325).

Empowering caregivers. Encourage parents to spend time each day talking with their child about the child’s time away from home (TABLE 325). Counsel parents/caregivers to expand their role. Knowing a child’s friends, encouraging the child academically, and increasing communication are all associated with lower risks of bullying.26 Similarly, parental oversight of Internet and social media use is associated with decreased participation in cyberbullying.27

In addition, the Positive Parenting telephone-based parenting education curriculum has been shown to decrease bullying, physical fighting, physical injuries, and victimization of children.28 The research-based, family strengthening program emphasizes 3 core elements of authoritative parenting: nurturance, discipline, and respect or granting of psychologic autonomy. The program entails 15- to 30-minute weekly phone conversations between parents and educators, as well as videos and a manual.