Immunotherapies shape the treatment landscape for hematologic malignancies

Citation JCSO 2017;15(4):e228-e235

©2017 Frontline Medical Communications

doi https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0357

Related articles

Meeting the potential of immunotherapy: new targets provide rational combinations

Pancreatitis associated with newer classes of antineoplastic therapies

Submit a paper here

Antibodies evolve

Another type of immunotherapy that has revolutionized the treatment of hematologic malignancies is monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), targeting antigens on the surface of malignant B and T cells, in particular CD20. The approval of CD20-targeting mAb rituximab in 1997 was the first coup for the development of immunotherapy for the treatment of hematologic malignancies. It has become part of the standard treatment regimen for B-cell malignancies, including NHL and CLL, in combination with various types of chemotherapy.

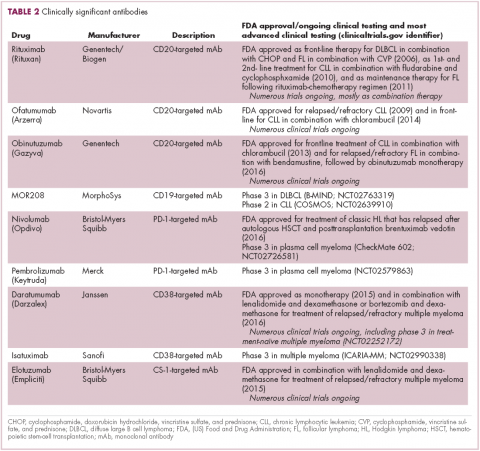

Several other CD20-targeting antibodies have been developed (Table 2), some of which work in the same way as rituximab (eg, ofatumumab) and some that have a slightly different mechanism of action (eg, obinutuzumab).11 Both types of antibody have proved highly effective; ofatumumab is FDA approved for the treatment of advanced CLL and is being evaluated in phase 3 trials in other hematologic malignancies, while obinutuzumab has received regulatory approval for the first-line treatment of CLL, replacing the standard rituximab-containing regimen.12

The use of ofatumumab as maintenance therapy is supported by the results of the phase 3 PROLONG study in which 474 patients were randomly assigned to ofatumumab maintenance for 2 years or observation. Over a median follow-up of close to 20 months, ofatumumab-treated patients experienced improved progression-free survival (PFS; median PFS: 29.4 months vs 15.2 months; hazard ratio [HR], 0.50; P < .0001).13 Obinutuzumab’s new indication is based on data from the phase 3 GADOLIN trial, in which the obinutuzumab arm showed improved 3-year PFS compared with rituximab.14Until recently, multiple myeloma had proven relatively resistant to mAb therapy, but two new drug targets have dramatically altered the treatment landscape for this type of hematologic malignancy. CD2 subset 1 (CS1), also known as signaling lymphocytic activation molecule 7 (SLAMF7), and CD38 are glycoproteins expressed highly and nearly uniformly on the surface of multiple myeloma cells and only at low levels on other lymphoid and myeloid cells.15

Several antibodies directed at these targets are in clinical development, but daratumumab and elotuzumab, targeting CD38 and CS1, respectively, are both newly approved by the FDA for relapsed/refractory disease, daratumumab as monotherapy and elotuzumab in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone.

The indication for daratumumab was subsequently expanded to include its use in combination with lenalidomide plus dexamethasone or bortezomib plus dexamethasone. Support for this new indication came from 2 pivotal phase 3 trials. In the CASTOR trial, the combination of daratumumab with bortezomib–dexamethasone reduced the risk of disease progression or death by 61%, compared with bortezomib–dexamethasone alone, whereas daratumumab with lenalidomide–dexamethasone reduced the risk of disease progression or death by 63% in the POLLUX trial.16,17

Numerous clinical trials for both drugs are ongoing, including in the front-line setting in multiple myeloma, as well as trials in other types of B-cell malignancy, and several other CD38-targeting mAbs are also in development, including isatuximab, which has reached the phase 3 stage (NCT02990338).

Innovative design

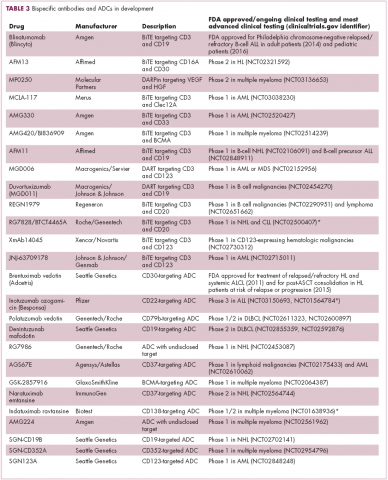

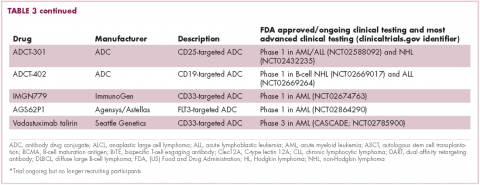

Newer drug designs, which have sought to take mAb therapy to the next level, have also shown significant efficacy in hematologic malignancies. Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) combine the cytotoxic efficacy of chemotherapeutic agents with the specificity of a mAb targeting a tumor-specific antigen. This essentially creates a targeted payload that improves upon the efficacy of mAb monotherapy but mitigates some of the side effects of chemotherapy related to their indiscriminate killing of both cancerous and healthy cells.

The development of ADCs has been somewhat of a rollercoaster ride, with the approval and subsequent withdrawal of the first-in-class drug gemtuzumab ozogamicin in 2010, but the field was reinvigorated with the successful development of brentuximab vedotin, which targets the CD30 antigen and is approved for the treatment of multiple different hematologic malignancies, including, most recently, for posttransplant consolidation therapy in patients with Hodgkin lymphoma at high risk of relapse or progression.18

Brentuximab vedotin may soon be joined by another FDA-approved ADC, this one targeting CD22. Inotuzumab ozogamicin was recently granted priority review for the treatment of relapsed/refractory ALL. The FDA is reviewing data from the phase 3 INO-VATE study in which inotuzumab ozogamicin reduced the risk of disease progression or death by 55% compared with standard therapy, and a decision is expected by August.19 Other ADC targets being investigated in clinical trials include CD138, CD19, and CD33 (Table 3). Meanwhile, a meta-analysis of randomized trials suggested that the withdrawal of gemtuzumab ozogamicin may have been premature, indicating that it does improve long-term overall survival (OS) and reduces the risk of relapse.20

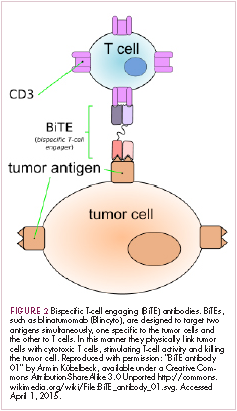

Bispecific antibodies that link natural killer (NK) cells to tumor cells, by targeting the NK-cell receptor CD16, known as BiKEs, are also in development in an attempt to harness the power of the innate immune response.