Immunotherapies shape the treatment landscape for hematologic malignancies

Citation JCSO 2017;15(4):e228-e235

©2017 Frontline Medical Communications

doi https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0357

Related articles

Meeting the potential of immunotherapy: new targets provide rational combinations

Pancreatitis associated with newer classes of antineoplastic therapies

Submit a paper here

The treatment landscape for hematologic malignancies is evolving faster than ever before, with a range of available therapeutic options that is now almost as diverse as this group of tumors. Immunotherapy in particular is front and center in the battle to control these diseases. Here, we describe the latest promising developments.

Exploiting T cells

The treatment landscape for hematologic malignancies is diverse, but one particular type of therapy has led the charge in improving patient outcomes. Several features of hematologic malignancies may make them particularly amenable to immunotherapy, including the fact that they are derived from corrupt immune cells and come into constant contact with other immune cells within the hematopoietic environment in which they reside. One of the oldest forms of immunotherapy, hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (HSCT), remains the only curative option for many patients with hematologic malignancies.1,2

Given the central role of T lymphocytes in antitumor immunity, research efforts have focused on harnessing their activity for cancer treatment. One example of this is adoptive cellular therapy (ACT), in which T cells are collected from a patient, grown outside the body to increase their number and then reinfused back to the patient. Allogeneic HSCT, in which the stem cells are collected from a matching donor and transplanted into the patient, is a crude example of ACT. The graft-versus-tumor effect is driven by donor cells present in the transplant, but is limited by the development of graft-versus-host disease (GvHD), whereby the donor T cells attack healthy host tissue.

Other types of ACT have been developed in an effort to capitalize on the anti-tumor effects of the patients own T cells and thus avoid the potentially fatal complication of GvHD. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) therapy was developed to exploit the presence of tumor-specific T cells in the tumor microenvironment. To date, the efficacy of TIL therapy has been predominantly limited to melanoma.1,3,4

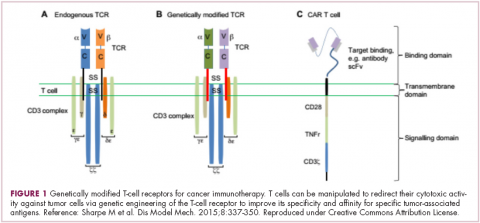

Most recently, there has been a substantial buzz around the idea of genetically engineering T cells before they are reintroduced into the patient, to increase their anti-tumor efficacy and minimize damage to healthy tissue. This is achieved either by manipulating the antigen binding portion of the T-cell receptor to alter its specificity (TCR T cells) or by generating artificial fusion receptors known as chimeric antigen receptors (CAR T cells; Figure 1). The former is limited by the need for the TCR to be genetically matched to the patient’s immune type, whereas the latter is more flexible in this regard and has proved most successful.

CARs are formed by fusing part of the single-chain variable fragment of a monoclonal antibody to part of the TCR and one or more costimulatory molecules. In this way, the T cell is guided to the tumor through antibody recognition of a particular tumor-associated antigen, whereupon its effector functions are activated by engagement of the TCR and costimulatory signal.5

Headlining advancements with CAR T cells

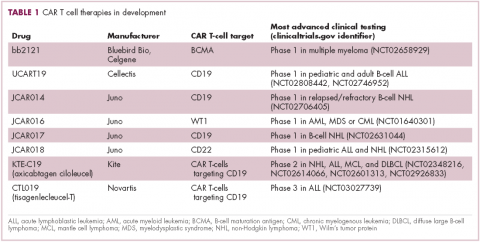

CAR T cells directed against the CD19 antigen, found on the surface of many hematologic malignancies, are the most clinically advanced in this rapidly evolving field (Table 1). Durable remissions have been demonstrated in patients with relapsed and refractory hematologic malignancies, including non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), and acute lymphoblastic lymphoma (ALL), with efficacy in both the pre- and posttransplant setting and in patients with chemotherapy-refractory disease.4,5

CTL019, a CD19-targeted CAR-T cell therapy, also known as tisagenlecleucel-T, has received breakthrough therapy designation from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of pediatric and adult patients with relapsed/refractory B-cell ALL and, more recently, for the treatment of adult patients with relapsed/refractory diffuse large B cell lymphoma.6

It is edging closer to FDA approval for the ALL indication, having been granted priority review in March on the basis of the phase 2 ELIANA trial, in which 50 patients received a single infusion of CTL019. Data presented at the American Society of Hematology annual meeting in December 2016 showed that 82% of patients achieved either complete remission (CR) or CR with incomplete blood count recovery (CRi) 3 months after treatment.7

Meanwhile, Kite Pharma has a rolling submission with the FDA for KTE-C19 (axicabtagene ciloleucel) for the treatment of patients with relapsed/refractory B-cell NHL who are ineligible for HSCT. In the ZUMA-1 trial, this therapy demonstrated an overall response rate (ORR) of 71%.8 Juno Therapeutics is developing several CAR T-cell therapies, including JCAR017, which elicited CR in 60% of patients with relapsed/refractory NHL.9

Target antigens other than CD19 are being explored, but these are mostly in the early stages of clinical development. While the focus has predominantly been on the treatment of lymphoma and leukemia, a presentation at the American Society for Clinical Oncology annual meeting in June reported the efficacy of a CAR-T cell therapy targeting the B-cell maturation antigen in patients with multiple myeloma. Results from 19 patients enrolled in an ongoing phase 1 trial in China showed that 14 had achieved stringent CR, 1 partial remission (PR) and 4 very good partial remission (VGPR).10