Meeting the potential of immunotherapy: new targets provide rational combinations

Citation JCSO 2017;15(2):116-121

©2017 Frontline Medical Communications

doi https://doi.org/10.12788/jcso.0336

Submit a paper here

The relationship between the immune system and tumors is complex and dynamic, and for immunotherapy to reach its full potential it will likely need to attack on multiple fronts. Here, we discuss some of the latest and most promising developments in the immuno-oncology field designed to build on the successes and address limitations.

The anti-tumor immune response

Cancer is a disease of genomic instability, whereby genetic alterations ranging from a single nucleotide to the whole chromosome level frequently occur. Although cancers derive from a patient’s own tissues, these genetic differences can mark the cancer cell as non-self, triggering an immune response to eliminate these cells.

The first hints of this anti-tumor immunity date back more than a century and a half and sparked the concept of mobilizing the immune system to treat patients.1-3 Although early pioneers achieved little progress in this regard, their efforts provided invaluable insights into the complex and dynamic relationship between a tumor and the immune system that are now translating into real clinical successes.

,We now understand that the immune system has a dual role in both restraining and promoting cancer development and have translated this understanding into the theory of cancer immunoediting. Immunoediting has three stages: elimination, wherein the tumor is seemingly destroyed by the innate and adaptive immune response; equilibrium, in which cancer cells that were able to escape elimination are selected for growth; and escape, whereby these resistant cancer cells overwhelm the immune system and develop into a symptomatic lesion.4,5

Immuno-oncologists have also described the cancer immunity cycle to capture the steps that are required for an effective anti-tumor immune response and defects in this cycle form the basis of the most common mechanisms used by cancer cells to subvert the anti-tumor immune response. Much like the cancer hallmarks did for molecularly targeted cancer drugs, the cancer immunity cycle serves as the intellectual framework for cancer immunotherapy.6,7

Exploiting nature’s weapon of mass destruction

Initially, attempts at immunotherapy focused on boosting the immune response using adjuvants and cytokines. The characterization of subtle differences between tumor cells and normal cells led to the development of vaccines and cell-based therapies that exploited these tumor-associated antigens (TAAs).1-6

Despite the approval of a therapeutic vaccine, sipuleucel-T, in 2010 for the treatment of metastatic prostate cancer, in general the success of vaccines has been limited. Marketing authorization for sipuleucel-T was recently withdrawn in Europe, and although it is still available in the United States, it is not widely used because of issues with production and administration. Other vaccines, such as GVAX, which looked particularly promising in early-stage clinical trials, failed to show clinical efficacy in subsequent testing.8,9

Cell-based therapies, such as adoptive cellular therapy (ACT), in which immune cells are removed from the host, primed to attack cancer cells, and then reinfused back into the patient, have focused on T cells because they are the major effectors of the adaptive immune response. Clinical success with the most common approach, tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL)

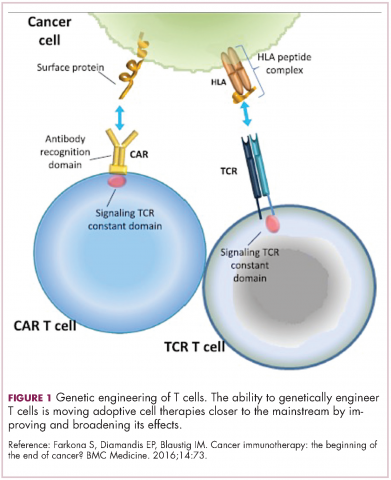

Two key techniques have been developed (Figure 1). T-cell receptor (TCR) therapy involves genetically modifying the receptor on the surface of T cells that is responsible for recognizing antigens bound to major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules on the surface of antigen-presenting cells (APCs). The TCR can be altered to recognize a specific TAA or modified to improve its antigen recognition and binding capabilities. This type of therapy is limited by the fact that the TCRs need to be genetically matched to the patient’s immune type.

Releasing the brakes

To ensure that it is only activated at the appropriate time and not in response to the antigens expressed on the surface of the host’s own tissues or harmless materials, the immune system has developed numerous mechanisms for immunological tolerance. Cancer cells are able to exploit these mechanisms to allow them to evade the anti-tumor immune response. One of the main ways in which they do this is by manipulating the signaling pathways involved in T-cell activation, which play a vital role in tolerance.12